Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Simplifying Pigment Detective Work

Art Conservation: Scientists remove a strong acid treatment in a Raman spectroscopy technique for measuring paint composition

by Sarah Everts

May 5, 2011

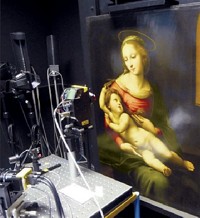

When conservation scientists examine the pigment composition of great masterpieces, they use techniques that produce minimal damage to the paintings. Now one of these sensitive techniques may have gotten one step simpler.

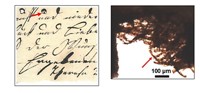

Researchers led by Kristin Wustholz, a chemist at the College of William & Mary, made the improvement to a protocol called surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS). The method pinpoints the chemical make-up of pigment from just a single microscopic particle of the colorant, instead of needing large, destructive samples required for more traditional techniques. The pigment particles required for SERS analysis are "so small they are not visible to the human eye," Wustholz says. Removing one does not change the appearance of the masterpiece.

In the standard SERS technique, a researcher picks off a pigment particle from the painting and treats it with strong acid to separate the pigment from paint binders, varnishes, and other media. The pigment can then adsorb to a silver nanoparticle mixture. Using a Raman spectrometer, the scientist then takes a vibrational spectrum of the pigment-nanoparticle mixture to identify the pigment's chemical signature. The silver nanoparticle acts like a signal amplifier for the pigment particle, allowing scientists to get useful information from the tiny sample.

Using two 18th century oil paintings in the collection of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Wustholz collaborated with Williamsburg conservator Shelley Svoboda to discover that the acid step wasn't necessary (Anal. Chem., DOI: 10.1021/ac200698q).

Wustholz's team used the new technique to identify the lip pigment in the oil painting Portrait of William Nelson by Robert Feke. They found that the red color was carmine lake, an organic pigment extracted from insect scales. The team also used the technique to study flesh tones in Portrait of Isaac Barré by Sir Joshua Reynolds. The team chose Reynolds' painting because he typically added to his paint a complex mixture of binders and varnishes, which would normally be removed by the acid treatment. Keeping these components, which can produce spectroscopic noise, in the sample was a good way to test the limits of the new protocol, Wustholz says. The team could still identify the pigment, which was again carmine lake.

Francesca Casadio, a senior conservation scientist at the Art Institute of Chicago, praises the simpler protocol. "When dealing with just one or two particles of pigment, there's always a risk of losing the pigment at some point," she says. "The fewer steps you have, the better."

In addition, the new protocol allows researchers to perform fluorescence spectroscopy on the same sample, allowing them to confirm pigment identity.

The next step, says Marco Leona, who heads the science research department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is to validate the acid-free protocol for other kinds of artwork pigments, beyond carmine lake in oil paintings from the 18th century. Because variables such as the paint type, the painting's age and physical condition, and the process used to make the organic pigment could all affect the new protocol's reliability, Leona says more testing is necessary.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter