Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Detecting A Bacterial Toxin's Glow

Synthetic Sensors: New probe fluoresces when it binds to a common bacterial molecule

by Sarah Webb

June 2, 2011

When bacterial endotoxins, building blocks of the outer membrane in many disease-causing bacteria, enter the human body, they spur an immune response and can lead to sepsis. Now researchers have built a simple lipid-based sensor that glows in the presence of bacterial endotoxins (J. Am. Chem. Soc., DOI: 10.1021/ja204013u).

Bacterial endotoxins, also called lipopolysaccharides, consist of negatively charged sugars attached to a lipid structure that helps to form the outer membrane of the bacteria. Traditionally scientists have detected these toxins using a test derived from blood cells from horseshoe crabs. Previous attempts to develop chemical sensors for LPS have either involved complicated syntheses of molecules that bind it or required complex detection strategies, says Carsten Schmuck of the University of Duisberg-Essen, in Germany.

In the new sensor that Schmuck and his colleagues developed, a synthetic lipid containing a fluorophore binds to lipopolysaccharides to produce a fluorescent signal. The chemists designed the synthetic lipid inspired by a known lipopolysaccharide-binding antibiotic, polymyxin B, which contains a greasy tail attached to a peptide decorated with several positively charged amines.

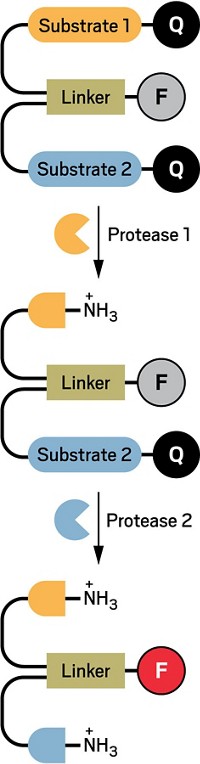

They constructed the synthetic lipid from two smaller lipids in a simple process. Both lipid molecules contained positively charged amino acids in their polar head groups to bind the lipopolysaccharide. One of the lipids contained a fluorophore. When the researchers mixed the two smaller lipids together at a specific ratio and shined ultraviolet light on the mixture, diacetylene groups in the lipids’ hydrophobic tails cross-linked. The result was the full lipid that quenched the fluorescent signal.

The fluorescent signal returned when the researchers added bacterial endotoxin or Escherichia coli cells to the sensor. The new sensor could detect concentrations of the toxin down to 500 nM. The researchers found that the sensor did not glow in response to many other molecules, such as nucleotides or anionic sugars. But the protein bovine serum albumin did produce a small fluorescent response. Schmuck plans to improve the specificity of the sensor and eventually improve its sensitivity so it can detect toxin levels in the nanomolar range.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter