Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Algal Toxins Accumulate In Fish

Water Pollution: Eating fish from algae-covered lakes may expose people to toxins

by Melissae Fellet

August 5, 2011

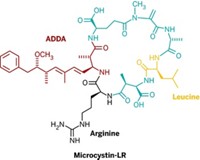

Fertilizer-loaded runoff from farmland and wastewater from cities drains into freshwater lakes around the world, feeding blue-green algae that produce toxins called microcystins. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that untreated drinking water accounts for 80% of human exposure to the toxic family of peptides. Now scientists report another exposure route that may be significant: eating freshwater fish (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es200285c). The results suggest that current calculations of microcystin exposure might underestimate the risk from food, the researchers say.

In Uganda, microcystin-producing cyanobacteria grow year round in some tropical lakes. Fish from these lakes and others feed millions of people. Limnologist Amanda Poste of Trent University, in Peterborough, Ontario, wondered if the fish accumulated microcystin in their tissues at levels that could harm humans.

Poste, then a graduate student at the University of Waterloo, in Ontario, and her colleagues collected about 500 fish representing 33 species from Lake Victoria and other Ugandan lakes. They also collected fish from two North American lakes with fleeting algal growth. For species that people consume whole, the team pulverized entire fish and examined the resulting powder. For other fish, they sliced off and pulverized chunks of the edible muscle tissue for testing. The researchers measured toxin levels using an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that detects any of the more than 80 members of the microcystin family. In setting a limit for human exposure to the toxins, WHO considers only one, an especially toxic variant called microcystin-LR.

The researchers found that fish toxin levels varied by species, with the highest concentrations measured in African fish. A small fish, Rastrineobola argentea, from the Napoleon Gulf of Lake Victoria had microcystin concentrations between 39 and 129 µg per kg of wet fish flesh. In comparison, the WHO’s daily exposure limit in people is 0.04 µg microcystin-LR per kg of body weight. So a 60-kg person who eats 100 g of fish daily—a typical amount for the frequent fish eaters living near the lake—would exceed the recommended limit when eating fish with toxin levels greater than 24 µg/kg, according to the researchers.

The study’s findings are important because previous research suggested that fish tissue was not a main source of human exposure to microcystins, says Wayne Carmichael, an emeritus professor at Wright State University. Ecologist Rainer Kurmayer at the Austrian Academy of Sciences’ Institute for Limnology credits the study’s comprehensive sampling of fish species and large number of fish collected.

But both Kurmayer and Carmichael note that still unknown are the specific microcystins in the fish tissue, which carry varying toxicity. Further analysis should also confirm the observed toxin levels using a different analytical method, Carmichael says, because ELISA’s strength is detecting the presence, not concentration, of the toxins.

Poste says the team wanted to understand the broad risk of microcystin exposure from fish and chose ELISA because it was easy to use at remote field sites. Still, the elevated toxin concentrations worry her. Even if most of the microcystins she detected were less toxic than microcystin-LR, she says, the total toxicity of the fish flesh could still reach harmful levels.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter