Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

A New Hazard From Bisphenol A?

Environmental Toxins: Bacteria chemically modify BPA, making it more toxic to fish

by Erika Gebel

August 5, 2011

The dust has yet to settle on whether bisphenol A (BPA) harms humans, but now people may start worrying about BPA’s chemical offspring. Researchers report that certain bacteria convert BPA into compounds more deadly to fish than BPA itself (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es200588w).

Industry produces millions of tons of BPA each year, mostly for making plastics. People ingest BPA or absorb it through their skin, ending up with levels that are detectable in serum and breast milk. The chemical structure of BPA is similar to estrogen, raising concerns that it could mimic the hormone and wreak havoc in the body, particularly in early life.

Max Häggblom of Rutgers University knew that a significant amount of BPA ends up in the environment, where bacteria could transform it to compounds with unknown properties and health effects. So Häggblom and colleagues added BPA to four species of Mycobacterium, a common genus of microbe that the researchers knew could chemically transform related compounds. When they monitored the products with gas-chromatography/mass spectrometry, they discovered that all four species could add one or two methyl groups to BPA.

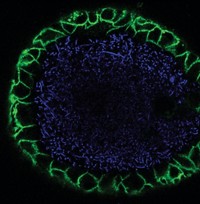

The researchers then added these compounds in varying concentrations, all higher than BPA’s usual levels in nature, to vials of water containing zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos and watched the fish develop. They found that it took ten times as much BPA as methylated BPA to kill half the zebrafish over five days.

Häggblom acknowledges that scientists have no data on whether these methylated BPA products exist in nature. But he hopes that environmental chemists will start looking for the compounds.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter