Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

No Progress In Nitrate Cleanup Of Mississippi River

Water Pollution: Nitrate leaving the river’s basin has increased 9% since 1980, according to new study

by Sara Peach

August 9, 2011

Despite decades of conservation efforts, nitrate pollution in the Mississippi River basin hasn’t improved. Between 1980 and 2008, nitrate levels have held steady at some sites in the river and its tributaries, while increasing by more than 70% at another, according to a new study by researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es201221s).

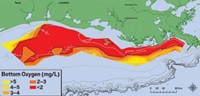

Since the mid-20th century, farmers in the Mississippi River basin have applied nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer to their crops. Some of that fertilizer washes into the Gulf of Mexico, where it feeds algal blooms. As bacteria devour the algae, they suck dissolved oxygen from the water and create a dead zone: an area of low-oxygen water where many organisms cannot survive.

The Gulf’s dead zone spanned more than 6,765 sq miles in July, according to the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium. During the 1980s and 1990s, the federal government established several voluntary programs to reduce fertilizer runoff. In 2008, a federal and state government task force set a goal to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus discharge to the Gulf by 45% by 2015.

But quantifying pollutant levels in the Mississippi River basin’s waters can be complicated. Weather variations, as in rainfall, cause year-to-year fluctuations in the amount of pollutants flowing into the rivers. These variables make it difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of conservation policies, says Lori A. Sprague, a researcher at USGS.

So Sprague and her colleagues applied a new analytical approach that uses a statistical method to control for yearly weather variations. The researchers analyzed data collected by USGS between 1980 and 2008 from eight sites on the Mississippi and its tributaries. The data set included more than 3,300 samples of river water and 110,000 measurements of river flow rate.

The researchers found that at sites on the Ohio, Iowa, and Illinois Rivers, which are tributaries of the Mississippi, nitrate pollution had not changed between 1980 and 2008. Meanwhile, pollution increased between 10 and 20% at three sites on the Mississippi River. At another site on the Mississippi and one on the Missouri River, pollution increased between 60 and 75%. Overall, the amount of nitrate leaving the Mississippi basin increased by 9%.

Sprague says some data are less dispiriting. Farmers typically apply fertilizer in the spring, and the researchers found that, on average, springtime nitrate concentrations decreased at some sites.

Unfortunately, she says, other data show that nitrogen pollution from the past may continue to cause problems. During dry periods, a large proportion of water in rivers comes from groundwater. The researchers found that nitrate levels increased when rivers were low, which they took as a sign that contaminated groundwater is seeping into rivers. Because nitrate can remain in groundwater for many years, conservation policies may take years or even decades to reduce pollution, Sprague says.

Gregory F. McIsaac, a professor emeritus of natural resources and environmental sciences at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, says the researchers’ method is a boon for studying trends in nitrate pollution.

But the trends they found are disappointing, he says: “We’ve been trying to address this problem for quite some time, and it doesn’t look like we’re making any progress.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter