Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

People

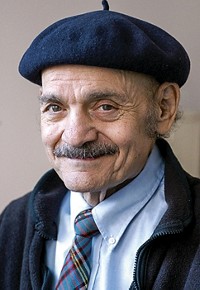

Har Gobind Khorana Dies At 89

Obituary: Nobel Laureate blazed new trails in chemical biology

by Susan J. Ainsworth

November 14, 2011

H . Gobind Khorana, 89, a biochemist and the Alfred P. Sloan Professor of Biology & Chemistry emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, died of natural causes in Concord, Mass., on Nov. 9.

Khorana, who won the 1968 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, made seminal contributions to the field of genetics through research on the genetic code and the mechanisms by which nucleic acids control the formation of proteins in cells.

“He revolutionized biotechnology with his pioneering work in DNA chemistry,” says Aseem Ansari, professor of biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. “Khorana was an early practitioner, and perhaps a founding father, of the field of chemical biology, because he brought the power of chemical synthesis to bear on a fundamental question of the nature of the genetic code.”

Khorana was born in India in the village of Raipur, in the Punjab region, which is now part of Pakistan. He received a bachelor’s degree in 1943 and a master’s degree in 1945, both in chemistry and biochemistry from Punjab University. A fellowship from the Indian government allowed him to study at the University of Liverpool in the U.K., where he earned a Ph.D. in 1948.

He conducted postdoctoral work at ETH Zurich. He then accepted a research fellowship at the University of Cambridge, before being recruited to Canada to join the British Columbia Research Council, in Vancouver, in 1952.

In 1960, Khorana joined the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where he became codirector of the Institute for Enzyme Research and a member of the biochemistry faculty.

At UW Madison, Khorana and colleagues helped decipher the mechanisms by which RNA codes for the synthesis of proteins. This work led to the Nobel Prize in 1968, which Khorana shared with Robert W. Holley of Cornell University and Marshall W. Nirenberg of the National Institutes of Health. Subsequently, he began to work on synthesizing functional genes.

Shortly after joining MIT in 1970, Khorana and his colleagues announced the successful synthesis of the yeast alanine transfer RNA (tRNA) gene, says Uttam RajBhandary, MIT’s Lester Wolfe Professor of Molecular Biology, who worked with Khorana for nearly 50 years.

Six years later, Khorana completed the synthesis of another tRNA gene, this time “with all the signals necessary for the gene’s expression within a cell,” RajBhandary says. “He then went on to show that it functioned in bacteria. This was the first example of a synthetic gene that was shown to be functional in a cell.” This work laid the groundwork for subsequent research on how a gene’s structure influences its function. Khorana retired from the MIT faculty in 2007.

That same year, at UW Madison, Ansari and Ken Shapiro, a professor and the chair of agricultural and applied economics, established the Khorana Scholars Program. It enables the exchange of top students at select Indian research institutions with students from UW Madison and other U.S. universities.

Khorana was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, and a member of ACS for more than 50 years.

He received numerous awards including the ACS Chicago Section’s Willard Gibbs Medal in 1974 and the National Medal of Science in 1987. In 2009, UW Madison held the 33rd Steenbock Symposium in honor of Khorana.

Khorana is survived by his son, Dave, and daughter, Julia. His daughter Emily Anne and his wife, Esther, predeceased him.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter