Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Nanomaterials

Solar Cells From A Paintbrush

Solar Energy: Paint-on solar cells would be cheap and easy to make

by Erika Gebel

December 14, 2011

To fabricate solar cells, engineers may someday trade their clean rooms for a paint smock. Researchers have developed a paste of semiconducting nanoparticles called solar paint that could lead to cheaper and easier-to-produce solar cells (ACS Nano, DOI: 10.1021/nn204381g).

Many researchers working on solar energy have focused on improving the efficiency of silicon-based solar cells. But silicon devices have a high price tag because of the specialized protocols and equipment needed, says Prashant Kamat of the University of Notre Dame. He points out that some researchers have avoided using silicon and created cells using quantum dots made from materials like lead sulfide. Unfortunately, the fabrication process for these quantum dot solar cells is still expensive and slow. To simplify and lower the costs of solar cell production, Kamat and his colleagues wanted to develop quantum dot materials that someone could paint onto any conductive surface without needing special equipment.

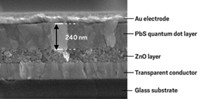

The quantum dots in these so-called solar paints are multi-layered nanoparticles. Each particle has a titanium dioxide nanoparticle core coated with compounds that can absorb photons, either cadmium sulfide or cadmium selenide. When a photon with the right energy hits the cadmium compounds, an electron escapes and TiO2 absorbs it.

The researchers used two methods for coating the TiO2 nanoparticles with the cadmium compounds: They physically mixed the ingredients together or used a process called the pseudo sequential ionic layer adsorption and reaction method to deposit CdS or CdSe onto the cores. To produce electrodes, the scientists suspended the nanoparticles in a water-alcohol mixture and then brushed the paste onto a transparent conducting material. They then tested the light-to-electricity conversion efficiency of cells built from these electrodes, using a cathode made from other materials and additional compounds to replenish the electrons lost by the cadmium compounds.

The best performing cell used paint containing a mixture of the CdS- and CdSe-coated TiO2 nanoparticles. Its light-to-electricity efficiency was 1%. The efficiencies of commercial silicon solar cells are usually between 10 and 15%.

The paints’ efficiencies, although low, are “quite decent” for a first-generation material, says Jin Zhang of the University of California, Santa Cruz. He thinks that the paint’s strength is that researchers can make it simply, quickly, and in large volume. But Zhang wonders about the materials’ long-term stability. Kamat and his team plan to study the paints’ stabilities, as well as to increase their efficiencies.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter