Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Coupled Effort Targets Cancer

Case study #1: Lonza and Genmab join again to create an antibody-drug conjugate

by Ann M. Thayer

March 12, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 11

Experienced guides bring equipment, know-how, and direction to scout new territory. When Genmab, a developer of monoclonal antibodies, decided to explore the field of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), it needed a capable adviser. It turned to Lonza in October 2011 for process development and manufacturing of its first ADC, called HuMax-TF-ADC.

COVER STORY

Coupled Effort Targets Cancer

Many antibody drugs are on the market, including the leukemia therapy Arzerra, developed by Genmab and its partner GlaxoSmithKline. But despite antibodies’ high specificity for cellular targets, not all are effective on their own.

Conjugating a highly potent compound to an antibody can increase the antibody’s efficacy while reducing harmful off-target effects from the toxic drug. ADCs also present an opportunity to create new targeted drugs, some of which are arising from resourceful combinations of antibodies and cytotoxic drugs that companies had shelved.

Making ADCs, however, requires the ability to handle biologics and potent compounds and to link them. ADCs must be manufactured under strict controls, even at very small scale during early stages of development. Lonza offers all of those skills.

“We were used to being able to manufacture an antibody in-house for early preclinical studies and for formulation development,” says Bodil Willumsen, associate director for chemistry, manufacturing, and controls at Genmab. In this case, however, “we have had to get the collaboration going with Lonza earlier so that they could manufacture material for toxicology and formulation development.”

HuMax-TF-ADC contains a fully human antibody targeted to tissue factor antigen, a protein involved in tumor signaling and angiogenesis. The antigen is highly expressed on the surface of many solid tumors, including pancreatic and colon cancers. The Danish company chose the antibody from a panel of more than 70 on the basis of its ability to bind to tissue factor, prevent signaling, engage immune effector mechanisms, and inhibit tumor growth in preclinical experiments.

Advancing the ADC will involve a supply chain that can be lengthy and complicated, because it requires antibody production, linker and cytotoxin synthesis, conjugation, and finished-dose formulation and filling. For Genmab, the antibody is no longer the final product but, like the drug-linker, has become an intermediate that must be sourced. For some ADCs, the production process involves multiple handoffs between contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs).

“The main reason for choosing Lonza for the whole package is because it makes the project management so much easier in not having to manage the interface between CMOs so closely,” Willumsen explains. Genmab is conducting cell line and bioassay development at its labs in the Netherlands and handling preclinical and clinical development in Copenhagen.

“Because we are working with Lonza’s cell line system, and we have a good working relationship with them for other antibody programs, they were definitely on our short list of CMOs,” she says. “Then it was a matter of deciding where to do the conjugation, and Lonza has a well-established facility in Visp, Switzerland.”

After making a concerted push, Lonza now has several years’ experience in ADCs and with various linker systems. “The project was extremely interesting to us because of being able to merge different technologies across the company to deliver a single product,” says Jason C. Brady, Lonza’s head of business development for conjugates and cytotoxics.

The highly potent small-molecule and conjugation chemistries were new areas for Genmab, which focuses primarily on biologics, Brady explains. Experts at Lonza’s facility in Slough, England, where the antibody will initially be produced, had worked with Genmab and were able to introduce the firm to the high-potency team in Visp.

Genmab had licensed the cytotoxic drug and linker technology in 2010 from Seattle Genetics, which received an up-front payment and the option to codevelop any resulting ADC product at the end of Phase I clinical trials. As a leader in drug-linker technology, Seattle Genetics has licensing and development agreements with at least 10 major drug and biotech firms. In 2011, it got U.S. approval for Adcetris, the first major anticancer ADC on the market.

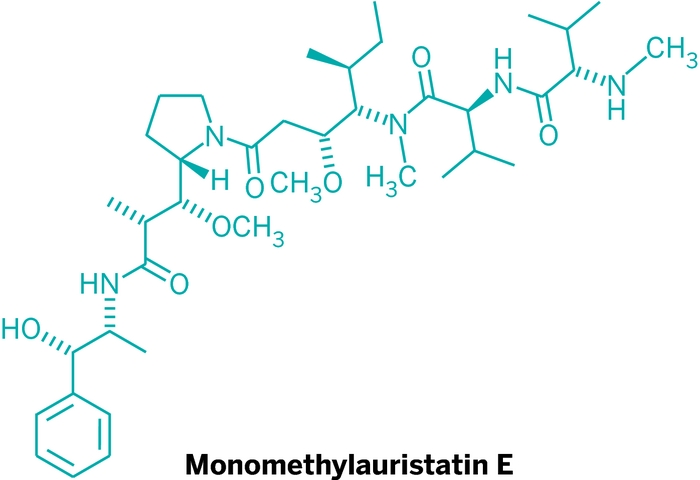

Genmab supplies the drug-linker to Lonza via separate contract manufacturing suppliers. “There are a number of CMOs involved in the supply chain of the drug-linker, which itself is a synthetically challenging molecule,” Brady points out. Seattle Genetics’ technology uses potent auristatins and linker systems designed to be stable in the bloodstream yet release the cell-killing agent once inside targeted cancer cells.

In addition to licensing its proprietary expression system, conducting process development, and supplying clinical material, Lonza will devise the required analytical methods for regulatory purposes. “The analytics associated with ADCs are really quite intricate,” Brady says, because the products are heterogeneous mixtures.

A typical antibody has multiple disulfide bridges that are broken with a mild reducing agent to open the structure and allow the drug- linker to attach. “Statistics dictate that you get a distribution of products with different numbers of drug molecules on them,” he says. An average drug-antibody ratio becomes an agreed-upon product specification.

The manufacturing process has to be robust and reproducible, and analytical characterization must show that the product is within the defined limits, Brady says. “The associated analytics are quite complicated because it is both a product mixture and a biologic that has these cytotoxic drugs hanging off of it.” The challenge for Lonza’s analytical scientists is to develop reliable methods on very low levels of highly toxic compounds.

For each ADC project, Lonza assigns small, dedicated teams for analytics, quality control, and process development. It cross-trains staff at its biologics and chemistry facilities, which must meet requirements for the aseptic handling of biologics and the containment of potent compounds while also operating under Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). “It’s all about keeping the product safe from people and protecting people from the product,” Brady says.

This year, Lonza will complete a $26 million expansion in Visp for clinical through commercial cytotoxic production that will allow it to offer a range of drug-linkers as well. Even at commercial scale, only small quantities of ADCs are needed—a kilogram is considered a big batch—but they are extremely expensive to produce. “They are complex, and you are combining very expensive raw materials,” Brady says. Through process and facility design, “we make sure we minimize batch failures.”

Both Willumsen and Brady say the collaboration is going smoothly and according to plan. Process development is under way for making the antibody, as is work on analytical methods. “We also have done some early non-GMP work to start process development of the conjugation piece,” Brady says.

“We have really benefited from working with a CMO that has tried this before,” Willumsen says. “It was important to have experts on board who are good at what they do and who can advise us about manufacturing ADCs and the associated analytics. Under its current business model, Genmab outsources extensively and thus relies heavily on skilled suppliers.”

Like many biotech firms, Genmab has been reducing costs and focusing on its most promising projects. Today it has about 180 employees, down from a high of 555 in 2008, at four sites. It is looking to sell an antibody manufacturing plant in Minnesota that it purchased in early 2008 for $240 million.

The recent approval of Adcetris and clinical successes for other late-stage products are positive signs for the future of ADCs. Willumsen and Brady are upbeat about the level of interest as companies partner and explore new linkers, targets, antibodies, and drugs. In April 2011, Genmab itself entered into a second agreement with Seattle Genetics for an anticancer agent called HuMax-CD74-ADC.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter