Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Education

Guiding Science Education

White House committee releases preliminary priorities for federal science education investment

by Andrea Widener

March 19, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 12

For the first time, the federal government is creating a strategic plan for its investment in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education, $2.9 billion in support in fiscal 2012. The effort will help focus funding on critical areas set out by the Administration and boost research into effective science teaching.

The final plan from the White House Office of Science & Technology Policy’s (OSTP) National Science & Technology Council will be released later this spring, but a sneak peek given to Congress in February proposes common goals across the 13 federal agencies that fund STEM education efforts.

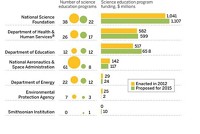

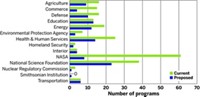

SOURCE: OSTP

SOURCE: OSTP

The preliminary strategic plan sets out goals of identifying effective teaching techniques, sharing such evidence-based approaches across agencies and with the larger education community, and increasing coordination among federal programs. It also suggests a new federal focus on four priorities: strengthening K–12 teacher education; heightening engagement in science; emphasizing undergraduate education, especially the first two years of college; and improving retention for groups traditionally underrepresented in science and engineering fields.

Carl E. Wieman, OSTP’s associate director for science, says that the ultimate aim is better coordination among agencies and leveraging each one’s particular assets and capabilities. “We want to create more of a community of learning within these programs as well as making programmatic adjustments to make them all more effective,” he says.

The preliminary plan strikes a good balance by guiding agencies toward important education priorities without being too prescriptive about how they incorporate those priorities into their own programs, says physicist Helen R. Quinn, chair of the National Research Council’s (NRC) Board on Science Education. “It is addressing the problems that can be addressed at this level: What is our overall mission and what are we trying to do?” she says.

The National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) and others in the education community have been calling for a federal STEM education strategic plan for years, and they are happy to see this first draft, says NSTA Executive Director Francis Q. Eberle.

Until now, each agency developed its own education efforts, so “there really was a lack of coordination among the programs. They didn’t always look for what was most needed” by the education community, Eberle says. “We like the approach OSTP has taken and the principles it has laid out.”

OSTP’s education review was prompted by the America Competes Reauthorization Act of 2010, which directed the science and technology council to do two things: identify all of the federal STEM education investments and create a five-year strategic plan. The committee created to respond to that mandate includes members of 11 federal agencies, plus Office of Management & Budget and OSTP staff.

The committee’s review of federal STEM education efforts, which was sent to Congress in December, identified 252 programs at 13 agencies totaling $3.4 billion in 2010—a large investment, but less than 1% of total government education spending in the U.S., the report points out. Since the data were collected, federal STEM funding has dropped slightly to $2.9 billion in both 2011 and 2012, with an increase of 3.4% requested for 2013.

Of 2010’s $3.4 billion, the review states, 72% went to broad STEM education efforts. The remaining $967 million was targeted specifically for workforce development by the different agencies.

The largest proportion of the STEM education funding, some $1.1 billion in 2010, went to programs that encourage groups traditionally underrepresented in STEM fields, with about half of the funding supporting students who are pursuing advanced degrees. That share is higher than might be expected because many federal programs list support for underrepresented groups as a primary or secondary goal, the review finds.

K–12 teacher training is another important funding area that emerged from the review, with 24 programs across the government totaling $312 million in 2010. Most of the support went toward training current teachers, with less than 1% going to programs that target only teachers in training.

Overall, the OSTP review found that although federal STEM education programs overlap based solely on broad goals and audience, there is surprisingly little actual duplication. Other reviews of these programs have found significant overlap but have stopped short of a more detailed assessment. The most recent such report was released by the Government Accountability Office in January, after the OSTP review was issued. It states that 83% of federal STEM programs overlap to at least some degree.

In a letter to GAO, Wieman recommends closer examination of the programs GAO considers overlapping based strictly on the goals and target audience. He says the programs likely are not similar at all. For example, two programs could be considered overlapping because they both focus on the same broad topic, such as learning, but one may target only college seniors whereas the other may target kindergarten through undergraduate students.

“Under this definition, two programs that are quite different but share even one element in each of those categories are counted as overlapping,” Wieman writes, recommending that GAO use OSTP’s more detailed analysis.

The strategic plan is based on a number of factors. Among them are President Barack Obama’s challenge to, within 10 years, train 100,000 more STEM teachers and graduate 1 million more college STEM majors, as well as address areas of need identified in previous education research and the missions of the specific agencies.

“The critical issue … is not whether the total number of investments is too large or whether today’s programs are overly redundant,” the report states. “The primary issue is how to strategically focus the limited federal dollars available so they will have a more significant impact in areas of national priority.”

Coordination among programs and sharing what works in the larger education community are both goals laid out in the preliminary strategic plan. But using research to identify the best ways to teach science to students is listed as the top priority.

“There is still a lot of research that needs to be done. We have some ideas of what can be successful, but often we are not sure what factors are necessary to ensure that what works at a small scale will be as successful when it is scaled up,” says Wieman, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist and an education researcher. “We are trying to establish a systematic means of building evidence on how well different programs are working and how to reliably scale up the most effective programs.”

NRC’s Quinn recommends that the OSTP committee be particularly cautious when deciding what constitutes evidence. “You have to be very careful to ask if it is valid evidence of the things we care about,” Quinn says. For example, do you want students to do well on standardized science tests—which has become the fallback measure of quality science teaching, she says—or do you want them to be interested in science and choose it as a career? “It seems like those are very different goals. Can you teach in a way that reaches both goals?” she asks. “You want people who do well in science and math and find it interesting.”

Recently recommended reforms from the President’s Council of Advisors on Science & Technology point in that direction. In a report released in February, PCAST says that increased retention alone would help produce 750,000 more undergraduate majors—three-quarters of the way to the President’s 1 million STEM majors challenge. Education research has already proven that using better teaching methods can improve undergraduate retention in STEM fields, especially among women, minorities, and other groups traditionally underrepresented in the sciences. “We should be basing science education programs on what we know about good practice,” NSTA’s Eberle says. “Some of the federal programs have very rigorous evaluation, others not so much.”

How evaluation and the other priorities will change agencies’ STEM education programs will be outlined in detail in the final strategic plan, to be released in May or June. “We hope to clearly delineate the most effective role each agency can play given its assets, mission, and capacities,” Wieman says. “We will be working with them to understand where they each best fit and how they can make the greatest contribution.”

According to OSTP Director John P. Holdren, these priorities have already helped guide STEM education funding in the proposed 2013 budget. NSF and the Department of Education both are slated for increases—including $60 million for a joint math education program—but STEM education funding is tagged for decreases at many other agencies.

Proponents of STEM education like Eberle want to make sure that no one area is improved at the cost of another. Specifically, Eberle worries that efforts to improve math education may take away from science, which has already proven to be the case with the federal education law No Child Left Behind. This law requires testing for K–12 reading, math, and science, but science is not a factor in determining awards or penalties. (The law is currently up for reauthorization, and many of these provisions are being reconsidered.) These requirements led to a significant decrease in the amount of time spent on science instruction, he says, up to 30% in some states.

“From our perspective, it is not one against the other,” Eberle says. Students have been shown to learn math best when it is taught in the context of science. “Research really says that coordinating and working together are important.

“We think that the investment the federal government has been making is very important,” and NSTA looks forward to helping push the priorities outlined in the strategic plan through Congress, Eberle says. “In this budget environment, if we can get anything through it would be terrific. We want to be able to keep STEM at the forefront.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter