Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

EPA Targets Flame Retardants

Agency scrutinizes chemicals over concerns about health and environmental effects

by Cheryl Hogue

October 29, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 44

New or revised standards for furniture flammability are not the only regulations in the works that will affect the market for flame-retardant chemicals. While California and the federal Consumer Product Safety Commission draw up their furniture flammability standards, the Environmental Protection Agency is assessing flame-retardant chemicals to determine whether they pose risks to human health and the environment and require regulation.

COVER STORY

EPA Targets Flame Retardants

EPA’s work on flame retardants is part of Administrator Lisa P. Jackson’s 2009 initiative to focus the agency’s chemical control program on substances of highest concern. Under this effort, EPA identifies chemicals that pose a concern to the public, moves quickly to evaluate these substances, decides what regulatory or other steps are needed to address risks, and initiates action. Factors that EPA uses to select these compounds include use in consumer products; presence in fluids or tissues of people; characteristics that make them persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic; potential to cause reproductive or developmental effects; and high production volume.

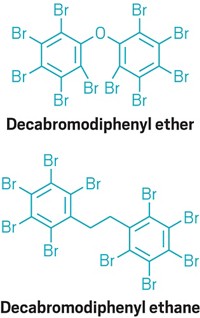

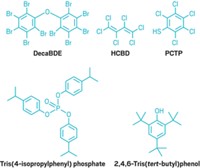

A class of flame retardants—polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs)—and hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD), another flame-retardant chemical, were among the six substances or classes of compounds EPA initially chose for this initiative. Under this effort, EPA is already acting on PBDEs and HBCD. In addition, the agency has targeted three other flame-retardant chemicals for risk assessments that eventually could lead to their regulation under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). More flame retardants are expected to come under EPA review soon, although any regulation of them would take years to come to fruition.

The agency’s current and planned actions on flame-retardant chemicals demonstrate the powers the agency has, and the roadblocks it faces, to regulate chemicals under TSCA. EPA primarily uses TSCA to screen new chemicals for safety before they enter the marketplace, although the law doesn’t require manufacturers to provide the agency with health or environmental toxicity data on the new substances. For this reason, EPA sometimes is unable to predict key properties, such as environmental persistence.

TSCA does give EPA the authority to restrict and ban chemicals already on the market, but the agency faces the risk of being overturned by courts when it takes such actions. The agency hasn’t used this authority for more than two decades after a court struck down EPA’s ban of asbestos, a known human carcinogen. Critics calling for reform of this law point to the daunting legal hurdles the agency must surmount before it can ban or restrict chemicals on the market that pose an unreasonable risk to human health.

TSCA aside, EPA’s effort to assess the risks posed by flame-retardant chemicals is complicated by lack of data. Hazard information is available for only a handful of the hundreds of flame-retardant chemicals on the market, says Heather M. Stapleton, an associate professor of environmental chemistry at Duke University who has studied flame retardants for more than a decade. Plus, information about people’s exposure to many of these substances is lacking.

As a broad class, flame-retardant chemicals tend to possess “a confluence of characteristics” that can be problematic for health or the environment, explains James J. Jones, acting assistant administrator of EPA’s Office of Chemical Safety & Pollution Prevention.

First, Jones tells C&EN, “they tend to be persistent by design because you want them to last for a long time—so the couch you bought has the same flame-retardant properties 10 years later.” Next, research studies have established that a number of flame-retardant chemicals, but not all, are bioaccumulative, Jones says. This means the compounds accumulate in the tissue of people and animals, as documented by human biomonitoring studies and field research with wildlife. Finally, Jones says, “they’re often toxic because they’re designed to be reactive, and reactive chemicals are more likely to be toxic than not.”

What’s more, flame retardants have a propensity to escape from the product they’re in, such as the foam padding in furniture or plastic housings of computers or televisions. They can enter the environment by volatilizing from the polymers they are used in or by flaking or crumbling off treated foam products, EPA tells C&EN. The compounds tend to end up in household dust and then move through the environment, leading to human and wildlife exposure, Jones points out. “If they were staying in place, there would be less to be concerned about,” Jones says.

EPA’s work on flame-retardant chemicals dates back to 2006, when the agency drew up a plan to study PBDEs after numerous research studies discovered these chemicals in human tissue and fluids, fish, birds, marine mammals, sediments, sludge, house dust, indoor and outdoor air, and supermarket foods. Experiments in animals have linked PBDEs to adverse neurobehavioral effects and thyroid hormone disruption. PBDEs have been used in polyurethane foam for furniture, mattress and carpet padding, plastics used in electronics casings, and commercial upholstery fabric.

From a regulatory perspective, PBDEs—which include penta-, octa-, and decaBDE—are a moot point. In 2003, California banned penta- and octaBDEs as of 2008; in the same year, the European Union banned these two BDEs as of 2004. Both cited the need to control health risks posed by people’s exposure to these substances. As a result, U.S. manufacturers and importers of PBDEs have ended, or are voluntarily ending, production. First, Great Lakes Chemical, now Chemtura, the sole U.S. manufacturer of pentaBDE and octaBDE, phased out production of the chemicals at the end of 2004. Then, at the end of 2009, after negotiations with EPA, Albemarle, Chemtura, and ICL Industrial Products agreed to phase out decaBDE by the end of 2012 for all but essential uses for which no alternatives are available.

HBCD may also be on the way out. Produced by a variety of companies, HBCD is added to polystyrene foam insulation for buildings and, to a lesser degree, applied to textiles. According to EPA, HBCD bioaccumulates, persists in the environment, is linked to hormone disruption, and is toxic to aquatic organisms. The substance is a candidate for the EU’s list of tightly regulated substances. In addition, a committee of scientific experts earlier this month proposed HBCD’s inclusion in the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (see page 17). In response, the chemical industry is slowly abandoning HBCD. In its place, a new polymeric flame retardant is being introduced that is expected to have less toxic properties (see page 39). However, the industry has not set a date to end production or use of HBCD.

Even though U.S. companies are voluntarily phasing out PBDEs and HBCD, EPA nevertheless is moving on them. In 2010, EPA unveiled detailed plans for coming up with alternatives for and regulating PBDEs and HBCD. In March, the agency proposed a regulation that would require companies that intend to include PBDEs in products imported into the U.S. to notify the agency before doing so. Such notice would give EPA an opportunity to restrict uses of PBDEs, which continue to be made and used abroad. Similarly, the agency has proposed a rule that would require companies to give EPA a heads-up before using HBCD on consumer textiles sold in the U.S. In addition, the agency proposed a rule that would require manufacturers and importers of the three PBDEs to conduct toxicity testing of the substances if they’re still in use beyond 2013.

The North American Flame Retardant Alliance, part of the chemical industry association American Chemistry Council (ACC), generally supports these EPA proposals, according to comments it filed with the agency. The alliance consists of Albemarle, Chemtura, and ICL Industrial Products.

As it works on these regulations, EPA is monitoring potential critical uses of decaBDE for which no other flame-retardant chemicals can be substituted, Jones says. A key application of decaBDE is in aircraft, where it is used in resins, sealants, floor panels, seats, life rafts, life vests, blankets, and storage bins, EPA tells C&EN. The agency is working with companies in this sector to ensure that they can provide the flying public with appropriate fire protection as decaBDE is withdrawn from the market, Jones says.

The phaseout of PBDEs and the decline in use of HBCD are creating a need for replacements. To help, EPA is developing information that product manufacturers can use to select alternatives. EPA’s Design for the Environment program released a draft report in July that discusses the performance and hazard trade-offs among some 30 alternatives to decaBDE. It will soon issue a similar draft assessment for alternatives to HBCD. Jones says EPA has gotten feedback from the public that these alternative assessments need to be broadened beyond substitute chemicals.

“Alternatives abound,” says Kathleen A. Curtis, national coordinator for the Alliance for Toxic-Free Fire Safety. The group is a coalition of activists who support techniques to reduce or eliminate the need to add flame-retardant compounds to products. Alternatives include increased use of sprinklers and smoke detectors, fire-safe cigarettes, and hiring more firefighters, she says. Improvements in product design are also an option, such as use of inherently fire-resistant materials—nonwoven polyester fibers, for example—or barriers between highly flammable materials such as foams and the outer fabric coverings of furniture, Curtis tells C&EN.

Meanwhile, EPA is expanding its scrutiny of flame-retardant chemicals. In June, the agency announced that during the next two years it will assess the risks posed by 2-ethylhexyl-2,3,4,5-tetrabromobenzoate (TBB), bis(2-ethylhexyl)-3,4,5,6-tetrabromophthalate (TBPH), and tris(2-chloroethyl)phosphate (TCEP).

According to published scientific literature, TBB and TBPH are components of at least two of Chemtura’s Firemaster products, which were created as replacements for pentaBDE and are used in plastic foams. TBB and TBPH are each linked to developmental problems and cause toxicity in aquatic organisms, according to EPA.

TCEP is used in plastics, polymeric foams, and synthetic fibers. The agency cites concerns based on lab studies showing TCEP to be mutagenic and limited evidence that it could cause cancer. The EU has proposed strict regulation of TCEP, pointing to reproductive toxicity concerns based on studies of lab animals.

After it assesses the three chemicals, EPA will decide whether to pursue regulation. “If the result of the evaluation shows there are some unacceptable risks, then we’re committed to taking the appropriate actions,” Jones says. If the agency finds no risks from these chemicals, it will make those findings public and turn its regulatory attention elsewhere, he adds.

The North American Flame Retardant Alliance did not respond to a request for comments about EPA’s move on TBB, TBPH, and TCEP. However, a Chemtura official has said that the company is submitting health and safety studies for the agency to use in its assessments (C&EN, Aug. 6, page 30).

Meanwhile, the number of flame retardants garnering attention from EPA is expected to grow. The agency is looking at dozens of flame retardants and developing a strategy for determining which pose the greatest potential concern, Jones says. EPA will select more of these compounds for detailed safety evaluations in coming months, he tells C&EN.

Hazard data are available for most of the five flame retardants EPA is currently focusing on, Jones says. “For some of them, we have pretty robust data,” he adds. The agency received some of this information through a voluntary program sponsored jointly by EPA, the activist group Environmental Defense Fund, and ACC. Through the program, many chemical manufacturers provided basic toxicity data on some 2,000 substances produced in amounts of 1 million lb per year or more.

Advertisement

Despite the availability of data for some substances, Jones agrees with Duke’s Stapleton, saying that EPA has little hazard information for many other flame-retardant chemicals. As part of its broad screening of dozens of flame-retardant chemicals, EPA will predict the toxicity of some compounds on the basis of their similarities to other chemicals, he says.

EPA is playing catch-up on toxicity data for flame retardants because many of these compounds were on the market before TSCA took effect on Jan. 1, 1977, Jones points out. As a result, EPA never reviewed them. Other flame-retardant chemicals that came to market after TSCA was enacted have undergone premanufacture examination by the agency, often in the absence of health and safety data. When EPA lacks this sort of information, which is not required by law, it relies on structure-activity relationships to estimate toxicity. “We try to do a really good job here using our predictive tools. Most of the time our predictive tools are on the mark,” Jones says.

But the tools aren’t foolproof. A case in point is TBB, Jones says. EPA’s premarket review of this chemical in 1995, done without manufacturer-supplied health and safety data, failed to identify that TBB is persistent and bioaccumulative, he says. The experience with TBB demonstrates why Congress needs to reform TSCA so that it requires manufacturers to supply health and safety data for new chemicals, Jones adds.

When EPA knows that a new chemical is persistent and bioaccumulative, the agency uses TSCA to limit production volume or to prevent widespread human exposure to the substance, Jones continues. With these controls, the use of a persistent and bioaccumulative substance in household goods such as furniture is unlikely, he says.

EPA doesn’t rely solely on toxicity data to assess chemicals. It includes information on exposure too. Some biomonitoring data are available that provide levels of a number of flame-retardant chemicals in people’s bodily fluids or tissues, Jones says. But for most of the compounds, EPA will rely on computer models to estimate exposure on the basis of data about flame retardants’ uses, he says.

To do these exposure estimates, the agency will rely heavily on information it collected through its Chemical Data Reporting Rule. Under this rule, manufacturers earlier this year provided EPA with data about production of chemicals and their uses.

After an assessment, if EPA decides to regulate a flame-retardant chemical, the agency faces extremely difficult—some critics say nearly impossible—legal requirements. These include demonstrating that the regulatory option the agency chooses is the least burdensome alternative for industry. Nonetheless, Jones says, EPA may attempt to use TSCA authority if it finds that a particular flame retardant poses an unreasonable risk to health or the environment. The agency’s action plan for HBCD lists this type of regulation as a possibility.

If EPA decides to restrict or ban a flame-retardant chemical because it poses an unreasonable risk, the agency must consider data on how well it works in preventing fire. Under TSCA, EPA must weigh the costs and benefits of a ban or other restriction. That analysis, Jones says, would take into account the efficacy of the flame retardant.

EPA, however, isn’t at that point yet. The agency is busy assessing the health and environmental risks of flame retardants.

“It is incumbent upon us to evaluate these compounds for safety,” Jones says. “The American public expects it, and that’s what our job is.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter