Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Arthur C. Cope Scholar: Jin-Quan Yu

by Carmen Drahl

February 27, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 9

For young Jin-Quan Yu, his favorite chore was like a mystical quest. Every month, he’d trek to a store 2 miles from his home in a remote village in southeast China to collect free salt for his family. The vendor would give Yu empty linen bags that once contained kilograms of salt. He’d take the bags home, wet them, and evaporate the water to collect the salt crystals that emerged, as if by magic. Yu says he wasn’t thinking about chemistry then, but he’s pretty sure the experience was the first indication that he had “good lab hands.”

Yu, 46, has since put his hands to use in C–H activation, arguably the hottest area of organometallic chemistry. He is “a phenom,” says University of California, Berkeley, organometallic chemist John F. Hartwig. “This guy is on fire and full of ideas.”

A desire to study medicine led Yu to earn a bachelor’s degree in chemistry at Shanghai’s East China Normal University. “In the village it could get really scary if you were ill,” Yu recalls. “We pretty much relied on Chinese herb extracts.” Yu earned his master’s under Shu-De Xiao at the Guangzhou Institute of Chemistry. There, Yu’s research led to a catalyst for ton-scale production of dihydromyrcenol, a lily-of-the-valley-scented compound used in shampoos and perfumes.

Fascinated by enzyme catalysis, Yu attended the University of Cambridge to earn a Ph.D. with Jonathan B. Spencer. He then joined E. J. Corey’s Harvard University lab as a postdoc, hoping to do total synthesis. But Corey steered Yu toward another project—allylic C–H oxidation. Yu was reluctant at first, but became enthralled with the challenge of converting normally inert C–H bonds to C–C or C-heteroatom bonds.

After Harvard, Yu began independent research back at Cambridge as a Royal Society Research Fellow. In 2004, he became an assistant professor at Brandeis University. In 2007, he moved to Scripps Research Institute, where he is currently a full professor. He’s garnered many honors, including a Sloan Research Fellowship, the Japanese Society of Synthetic Organic Chemistry’s Mukaiyama Award, and numerous awards from pharmaceutical companies.

“I consider Jin-Quan’s pivotal contributions to the C–H activation field to be some of the very best in the area,” says Yu’s Scripps colleague and chemistry chairman K. C. Nicolaou.

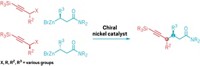

“Many groups have been focusing on sp2 C–H bond functionalization, but Dr. Yu recognized that the chemistry of sp3 C–H bond functionalization is potentially much richer,” says Huw M. L. Davies, who studies C–H activation at Emory University. In 2008, for example, Yu discovered the first palladium(II)-catalyzed coupling of sp3 C–H bonds with sp3 organoboron reagents. Yu’s team also developed the first palladium-catalyzed enantioselective C–H activation reactions. Yu says the key is using ligands that weakly coordinate to palladium.

“By the time I retire, I hope synthetic chemists, particularly those in the pharmaceutical industry, will use C–H activation on a daily basis, like they do cross-coupling,” Yu says.

In his spare time, Yu likes to play soccer. His favorite position? “Right wing,” Yu says. “I want to strike and score.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter