Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Coatings Influence Nanoparticle Toxicity

Surface Science: Changing the coating on silver nanoparticles alters the toxicity to mouse cells

by Sarah Webb

January 18, 2012

To understand the toxicity of nanoparticles, most scientists have focused on the materials’ metal cores. But now researchers have shown that the chemicals that decorate silver nanoparticle surfaces help determine the particles’ toxicity to mammalian cells (Langmuir, DOI: 10.1021/la2042058).

Known for their antibacterial properties, silver nanoparticles find use in medical devices, textiles, and other products. In 2010, Mitchel Doktycz of Oak Ridge National Laboratory and his colleagues reported that unlike other silver nanoparticles, those with fatty oleate coatings were not toxic to bacteria (Environ. Sci. Tech., DOI: 10.1021/es903684r). Those results led Doktycz and his team to wonder whether chemical coatings could make particular nanoparticles more toxic to bacteria but less toxic to eukaryotic cells.

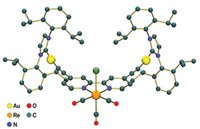

The researchers synthesized and purified silver nanoparticles with four different chemical surfaces. They then tested the particles’ toxicity toward mouse cell lines from the lung and immune system and used microscopy to look for damage to the cells’ membranes. Nanoparticles coated with an ammonium-containing polymer were the most toxic to cells, followed by those coated with proteins and oleates. Uncoated silver nanoparticles proved the least toxic. Lung epithelial cells were less likely to die or experience membrane damage than macrophages were.

The results offer insights that may help materials scientists match nanoparticles and their coatings with applications, says Anil Suresh, first author of the study and now a staff scientist in molecular medicine at City of Hope, a cancer research center in Duarte, Calif. Doktycz now wants to understand the details of how cells interact with these nanoparticles and their coatings, including how the cells might modify the surface chemicals.

This story’s first paragraph was clarified on Jan. 19, 2012, to say that the new research was done in mammalian cells.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter