Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Printer Toner Seals The Deal

Microfluidics: A simple approach makes paper-based labs-on-a-chip watertight

by Jeffrey M. Perkel

January 19, 2012

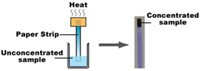

Paper-based diagnostic tests offer hope to healthcare providers with limited resources, who need cheap, rapid, and practical tests. But their open design can cause problems when the bodily fluids moving through them evaporate or get contaminated. A new study suggests a simple fix: Seal the devices with laser printer toner (Anal. Chem., DOI: 10.1021/ac202837s).

Using a store-bought printer, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo researcher Andres Martinez coated paper microfluidic devices on both sides with up to six layers of toner; he and his colleagues found that four layers made the devices watertight and protected samples from contamination. They found that liquids migrated faster through toner-encased channels than through untreated devices, an effect Martinez’s team attributed to reducing evaporation. But printing also applies heat, which inactivates up to 90% of the devices’ assay enzymes. To avoid the problem, the researchers created 1-mm-diameter reagent addition ports–that is, zones free of toner--and applied the enzymes after depositing the toner.

Sealing paper microfluidics with toner is both easy and cheap, Martinez says; he estimates it cost his lab about a penny per device. The process also enables simultaneous printing of instructions, images, and labels on the devices, which isn’t possible when researchers use other sealing approaches such as lamination. Now Martinez hopes to apply the technology to third-world healthcare needs. “The end goal,” he says, “is to be able to test and diagnose disease in the field at a very low cost”.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter