Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Microfluidic Device Quickly Tests Antibiotic Effectiveness

Medical Diagnostics: Rotating beads measure bacterial growth

by Aaron A. Rowe

April 24, 2012

A new microfluidic device spins magnetic microbeads to measure the proliferation of bacteria in minutes (Anal. Chem., DOI: 10.1021/ac300128p). The method could offer doctors a fast way to test the vulnerability of specific bacterial strains to antibiotics, its developers say, enabling better choices of medications for patients with stubborn infections.

To determine if an antibiotic can wipe out a person’s bacterial infection, hospital staff must currently culture the germs overnight and then watch how applying antibiotics affects the microbes’ survival, which takes an additional six hours. That’s far too slow, say researchers at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who developed the new device.

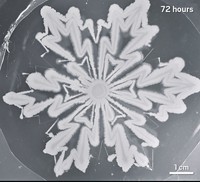

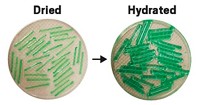

For their method, the team led by Raoul Kopelman adds a suspension of bacteria and magnetic beads to a microfluidic chip. The device then mixes this broth with mineral oil to produce oil-coated droplets, each containing microbes and a single bead. When placed in a rotating magnetic field produced by an electromagnet that the researchers designed, the beads spin. As the bacteria grow inside the droplets, they excrete chemicals that thicken the liquid. That goo slows the rotation of the magnetic beads, a deceleration that the scientists can measure as they watch the droplets through a microscope.

To test their device, the researchers mixed Escherichia coli bacteria with the antibiotic gentamicin at a range of concentrations. At low concentrations, the germs grew, slowing the beads’ rotation by 50% after 100 minutes. Meanwhile, at high levels of gentamicin, the microbes died, so the fluid’s viscosity stayed the same and the beads rotated at the same rate.

The researchers have now started a company called Life Magnetics to commercialize the new technique. They acknowledge that the technique still requires culturing a patient’s infection, but says that it requires less time because the viscosity measurements can be made in droplets that contain only 50 cells.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter