Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Antibody-Coated Particles Slow Tumor Growth

Drug Delivery: Polymer nanoparticles help antibodies target an extracellular matrix enzyme

by Aaron A. Rowe

May 22, 2012

Polymer nanoparticles coated with therapeutic antibodies arrest tumor growth in mice, chemists have discovered. To get the same effect with antibodies alone would require 30 times the dose (Nano Lett., DOI: 10.1021/nl301206p). The researchers who made the discovery think the particles could lead to cancer therapies with few side effects.

Rather than targeting the cancer cells themselves, the antibodies interfere with the body’s production of the extracellular matrix around the tumor cells. This matrix, which comprises proteins and polysaccharides, provides structural scaffolding for tumor tissue and encourages its growth. By inhibiting the extracellular enzyme lysyl oxidase (LOX), the antibodies block the crosslinking of collagen, a major component of the matrix. Without crosslinking, the matrix doesn’t stiffen and tumor growth slows.

Several labs have found evidence in both preclinical and human studies that interfering with the extracellular matrix could fight tumors. Unfortunately, some of these therapeutic antibodies that target matrix enzymes require large doses and, as a result, cause worrisome side effects.

Donald Ingber of Harvard University and his colleagues thought that nanoparticles could enhance the effect of the antibodies by concentrating them within tumors. Nanoparticles tend to accumulate in tumors because the growths are unusually permeable compared to healthy tissue. “Due to their nanoscale size, they passively enter the tumor but are difficult to wash out,” Ingber explains.

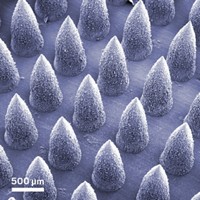

To test their hypothesis, the researchers made 220-nm-diameter nanoparticles from a biodegradable copolymer. They then covalently attached the LOX antibodies to the polymer using carbodiimide chemistry.

The Harvard researchers then injected the nanoparticles into mice with mammary tumors. After 12 days, tumors in all the mice had grown, but those treated with the coated nanoparticles were about half the size as those treated with an equivalent dose of free LOX antibody. Microscope images showed that untreated tumors, which had grown even more, had collagen fibers that were four times as thick as ones found in nanoparticle-treated tumors.

Although the new strategy is clever, Szu-Wen Wang, a nanomedicine researcher at the University of California, Irvine, points out that the nanoparticle treatments did not actually shrink the tumors.

Ingber thinks that targeting multiple matrix proteins may slow growth even further. His team is working on developing such particles.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter