Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Graphene Finds Environmental Use

Nanomaterials: The versatile carbon nanomaterial can serve as a barrier to unwanted gaseous mercury

by Naomi Lubick

June 27, 2012

Graphene has been hailed as a wonder product by materials engineers looking for faster circuits to replace silicon. Now a group at Brown University has discovered a new use for the oxidized form of these nanoscale carbon sheets: chemical barriers. A thin layer of graphene oxide, about 10 atoms thick, prevents most of the gaseous mercury from escaping from a closed glass container, the researchers found (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es301377y).

Brown’s Robert Hurt and his colleagues had previously tested how much mercury escapes from crushed compact fluorescent light bulbs contained in plastic bags on the way to recycling. Most of the toxic heavy metal seeped out (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es8004392). He thought lining bags with graphene might hold the mercury in.

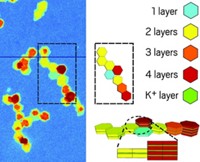

Because making large sheets of pure graphene is difficult, Hurt’s graduate student Fei Guo made graphene oxide by exfoliating pure graphite. From a watery suspension, the researchers dried the graphene oxide to create a film atop a plastic sheet.

The team set this layered plastic-and-graphene barrier above a pool of mercury in a glass container. After air flowed across the surface of the barrier and out of the container, a vapor analyzer measured its mercury content.

The membrane blocked 90% of the mercury that a naked plastic sheet would have let through. That was better containment than was provided by other proposed barriers to mercury vapors, including a nanoclay-coated plastic layer that blocked only 29%. The researchers plan to make the graphene layer thinner and therefore cheaper. Hurt thinks the film could find several other uses, such as preventing the release of volatile organic compounds from fabrics into a room.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter