Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Coatings

Slippery Coating Keeps Metals Frost-Free

Materials Science: Oil-infused textured surface could prevent ice buildup on airplane wings and refrigerator coils

by Prachi Patel

June 15, 2012

CORRECTION: This story was updated on July 12, 2012. The sentence that previously read, “Today’s defrosting techniques involve either corrosive chemicals or periodic heating, which consumes power,” was updated to read, “Today’s defrosting techniques involve either environmentally harmful chemicals or periodic heating, which consumes power.”

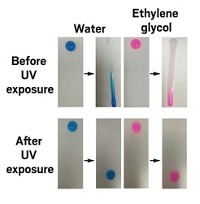

Researchers have found an easy way to encrust metals with a material that is super slippery and repels water (ACS Nano, DOI: 10.1021/nn302310q). By preventing water droplets from sticking to surfaces and then freezing, the coating could keep airplane wings, wind turbines, and refrigerator coils frost-free.

Today’s defrosting techniques involve either environmentally harmful chemicals or periodic heating, which consumes power. Meanwhile, most water-repellent coatings fail in high humidity. These coatings often have nanoscale features that cause water to bead up and bounce off. But in high-humidity, low temperature conditions, such as those on a snowy day, condensation builds up inside the nanostructures and can freeze.

Joanna Aizenberg and her colleagues at Harvard University previously had developed flat, ultrasmooth water-repellent coatings called slippery liquid-infused porous surfaces, or SLIPS (Nature, DOI: 10.1038/nature10447). These coatings consist of a porous network of polymer nanofibers infused with a lubricant.

The team thought a SLIPS could prevent frost buildup on metal surfaces, in addition to plastic, which they had coated in their previous work. To test the coatings on aluminum refrigerator coils, the researchers first deposited a bumpy polypyrrole layer on the metal. They then added DuPont’s lubricating Krytox oil to the layer and allowed it to infuse into the polymer matrix.

Unlike untreated aluminum, the treated metal surface stayed completely ice-free down to -4 ºC. Ice formed at lower temperatures, but it didn’t adhere well: The researchers could shake or melt it off in seconds.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter