Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Mining May Have Harmed 22% Of Streams In Southern West Virginia

Water Pollution: As mined land has grown, sensitive insect species have disappeared, researchers find

by Sara Peach

July 26, 2012

Decades of mountaintop-removal mining may have harmed aquatic life along more than 1,700 miles of streams in southern West Virginia, according to new research (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es301144q). Mining companies have converted 5% of the region to mountaintop mines. The resulting water pollution has caused so many sensitive species to vanish that 22% of streams may qualify as impaired under state criteria, the researchers report.

In the 1970s, many coal-mining companies in central Appalachia began to favor mountaintop-removal mining over traditional underground mining. At mountaintop mines, workers blast apart surface rock to gain access to coal seams and then dispose of waste rock and coal residues in nearby river valleys.

Large quantities of minerals leach from these waste sites, increasing salinity and the levels of trace metals downstream. Researchers have previously documented water pollution near individual mines, but they knew little about how far pollution flowed or how the region’s mines collectively affected water quality, says study author Emily Bernhardt of Duke University.

Using satellite images taken by NASA between 1976 and 2005, Bernhardt and her coauthors created maps of mountaintop mining in a 12,000-square-mile region of southern West Virginia. They found that companies had converted 5% of the land to mines during this period.

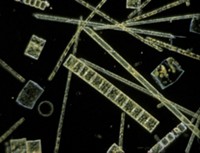

The researchers then mapped chemical and biological data from 223 streams that the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection had sampled between 1997 and 2007. They analyzed the data using standard statistical and modeling techniques, examining the relationships between the locations of operational and former mines, water pollution, and the presence of native aquatic insects such as mayflies and caddisflies.

Bernhardt’s group found that salinity and mineral levels in the region’s streams increased with the total area of mountaintop mines. The researchers also found that as the number of mines increased, fewer sensitive insect species were detectable downstream.

Bernhardt and her colleagues found substantial declines in insect diversity when companies had mined as little as 1% of upstream land. In areas where companies had converted about 5% of land, so many sensitive species disappeared that the streams would qualify as biologically impaired under criteria set by the state of West Virginia. The designation means the streams could be placed on a list of waterways that states must take steps to rehabilitate. More than 1,700 miles, or 22%, of the region’s streams drain land where 5% or more of the surface has been mined, according to the team’s analysis.

Benjamin M. Stout, an ecologist at Wheeling Jesuit University, in Wheeling, W. Va., says the study “confirms what most of us living in these communities have known all along, and that is these large-scale mines are truly damaging to our ecosystems.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter