Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Nanoparticle Conjugates Mimic RNA Interference

Molecular Biology: So-called nanozymes enter cells and cleave viral RNA without side effects

by Stu Borman

July 24, 2012

A new type of nanoparticle-based conjugate is a promising alternative to RNA interference (RNAi) agents for controlling gene expression by cutting RNA selectively in cells, according to its developers (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1207766109).

The researchers demonstrated the capabilities of the conjugates, which they call nanozymes, by using them to cleave viral RNA and suppress viral replication in cultured cells and in mice. The nanozymes so far seem to be more stable, longer lasting, and less toxic than RNAi agents. If those qualities prove out in future work, nanozymes may have potential as therapeutics for diseases that can be treated by controlling gene expression.

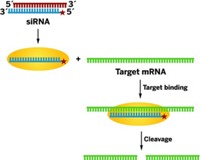

Chemist Y. Charles Cao and pathologist Chen Liu at the University of Florida designed nanozymes to mimic RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISCs). The working components of RNAi, RISCs use strands from small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and endonucleases to cleave RNA in cells.

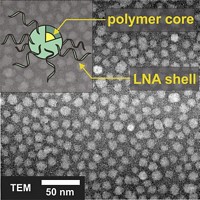

Nanozymes are gold nanoparticles decorated both with DNA sequences and endoribonucleases. The DNA sequences act like siRNA strands in that they complement the target RNAs. And the nanozyme endoribonucleases, like RISC endoribonucleases, are capable of cleaving those target RNAs.

Cao, Liu, and coworkers customized the DNA sequences of their nanozyme to recognize RNA in the genome of hepatitis C virus (HCV), a cause of hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer. The nanozymes cut HCV RNA in vitro. They also readily enter cultured virus-infected human liver cells and cleave HCV RNA, reducing viral protein expression and subduing viral replication without causing any obvious toxicity to the cells. When administered to an HCV mouse model, the nanozymes reduce viral RNA levels 99%, also without causing noticeable toxicity or side effects.

The nanozyme approach “has the potential to overcome difficulties associated with the use of siRNA-based drugs,” which are currently being evaluated in clinical trials, Cao says. Nanozymes “are more stable than RNAi therapeutics,” he says, because siRNAs are more susceptible than nanozymes to degradation by endogenous nucleases and agents expressed by pathogens. In addition, nanozymes “can easily enter cells and engage targets,” he says, whereas delivery of RNAi agents in a specific manner remains a major challenge. The group is now further evaluating antihepatitis nanozymes in animals, “such as mice with humanized livers,” Cao says.

Nanobiotechnology and RNAi specialist Peixuan Guo of the University of Kentucky comments that nanozymes represent “an innovative new approach for gene silencing in cells and in vivo.”

Chemistry professor Peter A. Beal at the University of California, Davis, whose areas of specialization include RNAi, says nanozymes “open up new possibilities for targeted RNA cleavage, particularly where RNAi with siRNAs is not possible or impractical.” siRNAs can cause side effects by binding sequences that are similar but not identical to the targets, and they can cause immune reactions by inducing endogenous cytokines. It will now be important to evaluate how nanozymes respond to DNA/target-RNA mismatches and to assess their ability to induce a range of different cytokines, Beal notes.

C. Shad Thaxton of Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine says the customized nanozymes “target hepatitis C virus with great results. This is the type of research that continues to advance therapeutic nanotech forward to fulfill the promise of exquisitely targeted and specific therapies for any number of human disease processes.”

Nathaniel L. Rosi, a specialist in nanoparticle assembly and materials discovery at the University of Pittsburgh, says the work represents one of the first examples of second-generation nanoparticle-based bioactive agents because it adds endonuclease to first-generation nanoparticle-nucleic acid constructs. These constructs control gene expression by using nucleic acid binding to block translation. A future third generation of such agents, he says, will also add targeting moieties to nanoparticle conjugates to provide greater selectivity for specific tissues such as tumors or specific organs such as liver.

Cao agrees with this vision of the future. “For use as therapeutics against other protein expression-related diseases such as cancer, the key hurdle will be how to deliver the nanozyme to specific organs or cell types,” he says. “In principle, our nanozyme platform allows us to add functionality that could direct nanozymes to specific tissues, organs, and even subcellular organelles that express target genes.” He and his coworkers hope to pursue that approach in future work.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter