Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Researchers Associate DNA Methylation Patterns With Honeybee Behavior

Chemical Ecology: Reversible epigenetic marks identify bees as either nurses or foragers

by Sarah Everts

September 17, 2012

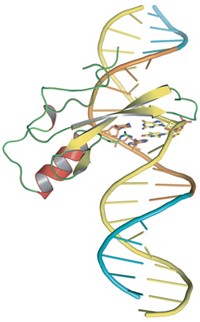

DNA methylation ensures the right genes are expressed in the right cell so that nose hair genes don’t get turned on in your pancreas. Now the epigenetic mark has been shown to also help determine the behavior of honeybee nurses and foragers.

For the first time, researchers have associated patterns of DNA methylation in an organism with reversible behavior—in the case of honeybees, the ability of nurses to switch to foragers and then back to nurses, explains Andrew P. Feinberg, an epigenetics researcher at Johns Hopkins University. Feinberg made the discovery in collaboration with Arizona State University bee biologist Gro V. Amdam (Nat. Neurosci., DOI: 10.1038/nn.3218).

Bees living in a hive are nearly identical in terms of genetics, Feinberg says, but the behaviors of different bee castes (queen, nurse, forager, worker) are remarkably different and have long made researchers suspect an epigenetic role in behavior.

Nurse bees that have just emerged from cocoons feed and clean bee larvae. When older, the nurse bees are able to turn into forager bees, which discover nectar and signal to worker bees the location of these food supplies, Feinberg says.

The research team found that otherwise genetically identical nurse and forager bees have different methylation patterns in 155 genes found in their brain cells, suggesting that the patterns dictate behavior. To prove this hypothesis, the team used “a strategy of hive trickery” by removing all the nurse bees while the foragers were away, the paper notes. When the foragers returned to the nurse-free hive, many reverted to a nursing role. The team found that after this role reversal, the methylation patterns in 57 genes from the former foragers had changed to correspond to nurse patterns. The genes that get reversibly methylated are involved in development and epigenetics, researchers say.

Scientists have long proposed that epigenetics affects behavior, comments Chuan He, who studies DNA methylation at the University of Chicago. “The most interesting part [of the paper] is that this effect is reversible. Reverting foragers back to nurses reestablishes methylation patterns.” This makes sense, he says, because “epigenetic modifications and their impact should be reversible.”

The team found no difference in the DNA methylation patterns of the brains of hive queens and hive workers, whose life destinies of laying eggs and ferrying pollen are sealed early in life and cannot change. Feinberg argues that the irreversible fates of queens and workers may be controlled at the more macroscale, heterochromatin level, where larger sections of the genome are silenced.

This latter result differs from that of a 2010 study finding methylation differences between queens and workers (PLoS Biol., DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000506). However, Australian National University’s Ryszard Maleszka, who led that study, says the two experiments are not comparable. The two research teams analyzed honeybees at different life stages, he explains: just after emerging from cocoons in the current work versus as established adults in the earlier research.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter