Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Researchers Evaluate Water Purification After Major Disasters

Water Treatment: The most successful methods employ tools that people are familiar with

by Janet Pelley

September 24, 2012

When disaster strikes, emergency responders try to help residents maintain clean drinking water by distributing antimicrobial treatments people can use at home. But responders lack rigorous evidence about which water treatment technologies do the most good. Now, a new study finds that top-performing technologies in the lab aren’t necessarily the most effective in real-life emergencies (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es301842u).

Between August 2009 and March 2010, Daniele Lantagne, of the Tufts University School of Engineering, trekked into four disaster zones to see if people given antimicrobial treatments actually improved their drinking water. She conducted surveys within eight weeks of a cholera outbreak in Nepal, major earthquakes in Indonesia and Haiti, and a flood in Kenya. “Disaster zones are chaotic and there are a lot of reasons why responders don’t conduct research in the first few weeks after a disaster,” says Lantagne. “In Haiti, I brought in 250 pounds of equipment to provide my own food and shelter for a month.”

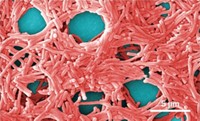

At each of 1,500 households in the four disaster areas, Lantagne noted whether people treated their water, and if they did, whether they used boiling, chlorine tablets, filters, or flocculant/disinfectant powder. She collected water samples at each house and cultured them in petri dishes, comparing numbers of bacteria to levels set by the World Health Organization as safe for drinking.

“What works in one place won’t work in another,” Lantagne says. In Haiti, emergency responders handed out two types of filters and chlorine tablets. With Thomas Clasen, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Lantagne found that about 68% of the households reduced bacteria counts to safe levels with tablets, a common method Haitians used to purify water before the earthquake, she says. But Indonesians shunned use of tablets provided by emergency responders, having had little or no experience with their use before the quake.

In Kenya, only 2.3% of households managed to reduce bacterial levels using flocculant/disinfectant powder, even though 5.9% of households reported using the powder. The powder performs better in the lab than any other technology does. But it failed in Kenya, because people didn’t receive sufficient training to follow the five steps it requires, Lantagne says.

So which methods work best in a disaster zone? Lantagne concludes that the methods must be easy to use and distribute, as well as familiar to the population before the emergency.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter