Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Alder Swamps Eat Up Mercury

Metals Pollution: Less methylmercury flows out of swamps with alder trees than flows in, researchers find, unlike other wetlands

by Naomi Lubick

December 3, 2012

A particularly toxic form of mercury may get destroyed in a place where researchers previously thought it was generated. A recent study of wetlands in Sweden has found that some, instead of creating methylmercury, serve as a sink for it (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es303543k).

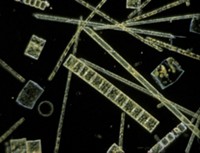

Past research in wetlands in Canada, the Florida Everglades, and elsewhere has pinpointed wetlands such as bogs, fens, and swamps as a source of methylmercury. This form of the metal is neurotoxic and can be readily taken up by fish and passed along to birds and humans. The mucky freshwater bodies receive inorganic mercury from the air, rain, and stream runoff. In the wetlands, sulfate-reducing microorganisms transform the mercury by adding a methyl group, making the metal bioavailable to fish and other creatures.

But a study of swamps in southern Sweden shows that wetlands that are home to black alder trees (Alnus glutinosa) may treat incoming mercury differently. Researchers led by Ulf Skyllberg of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Umeå measured various forms of mercury in the water flowing into the wetlands from upstream sources, in the wetland soils, and in water flowing downstream of the sites.

They found that one alder swamp released one- to two-thirds as much methylmercury as flowed into it, according to water samples taken from 2006 to 2010. They also collected soil samples five times over that period, which showed methylmercury was not accumulating there. The researchers also looked at an hour or so of flow at eight other alder-dominated wetlands during a May rainstorm and determined that more methylmercury flowed in than out.

But over the same four years, seven other wetland sites without alders released more methylmercury downstream than had flowed in. The team does not yet know what caused the difference, but they suspect that the nutrients present in alder swamps influence the growth of microbes that break down methylmercury.

Skyllberg and his colleagues suggest that people could restore alder swamps that have been drained across northern climes to prevent methylmercury from flowing downstream into freshwater streams and lakes. Such a buffer zone would be particularly useful, Skyllberg says, in logged areas or regions with peatlands or bogs, which tend to have high levels of methylmercury.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter