Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

A Shot Against Lyme Disease

As Lyme disease cases spread, a new vaccine is being developed amid worries about a hostile reception

by William G. Schulz

June 24, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 25

Lyme disease has become so widespread that it is today’s number one vector-borne illness in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC). Over the past 10 to 15 years, it has become of increasing concern to state and federal public health officials as infection hot spots have radiated from a few northeastern states across to the Midwest and all the way to the Pacific coast. Every state in the continental U.S. has reported at least one case of Lyme.

COVER STORY

A Shot Against Lyme Disease

To combat Lyme disease, public health experts say, there is urgent need for a safe and effective vaccine. This is especially true, they say, for high-risk groups—young children and adults who work or spend a great deal of time outdoors.

“The fact that there is no vaccine for an infection causing some 20,000 annual cases of Lyme is an egregious failure of public health,” says Stanley A. Plotkin, an emeritus professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and a consultant on vaccines to the drug industry.

But hope for a new vaccine may be on the horizon. An investigational Lyme disease vaccine being developed by Baxter International has shown promise in clinical trials in Europe. Baxter published clinical trial data on safety and immunogenicity for the new compound in May (Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, DOI: 10.1016/s1473-3099(13)70110-5). Yet work is moving slowly, and vaccine specialists say the caution is driven by a backlash from antivaccine groups that sank earlier Lyme treatments.

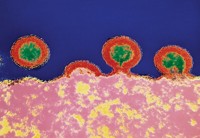

The Baxter vaccine prompts an antibody response by making use of a surface protein from the organism that causes Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi. The protein is called bacterial outer-surface protein A (OspA), but Baxter spliced the vaccine version together from variations found in the four B.burgdorferi species implicated in human disease. The protein was genetically altered to delete a fragment of the protein, the OspA1 epitope, that is implicated in the type of arthritic condition that can occur in Lyme disease. Researchers replace it with the related OspA2 epitope to eliminate the possibility of any cross-reactivity with human proteins that might cause disease symptoms.

As is the case with many human vaccines, Baxter’s formulation contains an aluminum adjuvant that reduces side effects and boosts the human immune response to the OspA antigen. In safety and immunogenicity testing, Baxter compared vaccine versions with and without the adjuvant. The vaccine with the adjuvant performed better both in terms of the elicited immune response and the reduced incidence of side effects such as fatigue, headache, and injection site reaction.

The clinical studies to date demonstrate that the vaccine—after three primary inoculations and one booster shot—will “induce substantial antibody titers against all targeted species of Borrelia, the causative agent of Lyme disease,” the May study says. “The novel multivalent OspA vaccine could be an effective intervention for prevention of Lyme borreliosis [Lyme disease] in Europe, and the USA and possibly worldwide.”

Baxter says the next step is an expanded safety and immunogenicity study, but plans for these further clinical studies “have not yet been finalized.”

The hope for Baxter’s vaccine, however, comes with a big dose of historical caution. In the late 1990s, two Lyme disease vaccines were approved in the U.S. by the Food & Drug Administration. One of those, ImuLyme, which was developed by Sanofi forerunner Pasteur Mérieux Connaught, never made it to market.

The other vaccine—Lymerix, developed by SmithKline Beecham, now GlaxoSmithKline—was put on the market in 1998 without much fanfare. The marketing approach for this product targeted potential patients at the expense of gaining buy-in from physicians, say experts in the infectious disease community who monitored or were involved in the Lymerix debut.

Much worse for GSK, the company was hammered with a false claim that Lymerix caused arthritis, a claim that gained traction in the echo chamber of some Lyme disease patient advocacy groups. The vaccine was pulled from the market in 2002 because of declining sales and a number of class-action lawsuits that were filed on the basis of still more false claims, says Gregory A. Poland of the Vaccine Research Group at the Mayo Clinic and other Lyme disease specialists. One claim was that Lymerix itself could give people Lyme disease.

Today, GSK does not respond to inquiries about Lymerix. It is against this backdrop that Baxter’s potential vaccine is being developed.

“We keep hearing about the Baxter vaccine, but there is no progress toward licensure,” Poland says. Given the continuing rhetoric from the antivaccine camp, he asks, “Why would any company invest in a product with no demand and lots of negatives” in terms of potential lawsuits and bad publicity?

Lymerix was not a grand slam in terms of efficacy and ease of vaccination, Poland says, “but it was something.” Nonetheless, he says, opposition groups were able to destroy the vaccine in the public mind and in the marketplace.

But Plotkin, who has been a consultant for Baxter, believes that times have changed and so, too, have the chances for bringing a successful Lyme disease vaccine to market. He believes that both CDC and FDA understand that any Lyme vaccine they might approve will need a stronger endorsement from them than what the GSK vaccine got. Likewise, he says, public health officials and drugmakers will have to emphasize physician buy-in—especially with the pediatricians, family doctors, and other practitioners who see patients for routine health matters.

For the vaccine itself, Plotkin and others say, a treatment that requires multiple inoculations and boosters is problematic because of patient compliance. So far, the Baxter Lyme vaccine candidate—as Lymerix before it—requires multiple doses. Also, they say, a profitable vaccine will need to be approved for use in both children and adults because children represent the highest risk group for contracting Lyme. The Baxter drug has not been tested for safety and efficacy in children.

As for antivaccine or hostile Lyme disease patient advocacy groups, “engaging people from the start is the thing to do” to win widespread public acceptance, Plotkin says. “We have to explain why a vaccine is safe and effective and that it’s not going to cause Lyme disease.”

On the other hand, Poland, who studies vaccine response in children and adults and has written about the history of Lymerix, is skeptical. He says the denialists and conspiracy theorists have not gone away. “They aren’t interested in debating science,” Poland says. He points to the disproven claim that the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine causes autism as an example of another case where an assertion not backed up by scientific evidence has been forwarded as fact.

Without a vaccine or other effective preventive measures, early diagnosis of Lyme disease becomes critical, medical experts say. Most diagnoses of Lyme disease are made courtesy of the unmistakable bull’s-eye rash around the tick bite that occurs in some 70% of infected patients. For others, a constellation of symptoms including visible tick bites, flu-like illness, and arthralgia, move doctors toward a Lyme diagnosis. Laboratory tests confirm the presence of Lyme, but often after a lengthy time.

The disease can mean serious illness and weeks of treatment depending on how far the ailment has progressed. Early-stage treatment includes oral administration of antibiotics such as doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime axetil. In later stages of the disease, treatment often includes intravenous administration of powerful compounds such as ceftriaxone or penicillin over a period of several weeks. There is no evidence for a chronic form of infection, but many experts say there is some evidence for chronic conditions such as pain and fatigue, and cardiac and neurologic/psychiatric problems that might result from an infection that is not treated early.

There are some people, medical experts say, who have probably suffered more than one bout of Lyme disease, particularly those who live in high-risk areas of the upper Midwest and northeastern states. There, and in other areas of the U.S. where Lyme is spreading, field mice and exploding populations of white-tailed deer sustain a growing reservoir of B. burgdorferi. Ticks pick up the bacteria from these animals and subsequently transmit it to humans.

That’s why another approach to fighting Lyme disease spread is a so-called reservoir vaccine, explains C. Ben Beard, chief of the Bacterial Diseases Branch in CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases. A group of researchers in New York state reported in 2006 that an oral vaccine for mice protected 89% of those immunized (Vaccine 2006, DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.089). But Beard says methods of delivering adequate oral doses of vaccine to wild mice to break the Lyme disease cycle may prove difficult.

In the absence of a vaccine, preventive measures will continue to be a top priority for CDC, Beard says. “We do everything in relation to that goal,” he notes. “It’s a challenge, yes, but impossible, no.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter