Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biomarkers

Early Detection Of Preeclampsia

Biomarkers are leading to tests to identify the life-threatening pregnancy complication before it becomes deadly

by Celia Henry Arnaud

December 2, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 48

Eleni Z. Tsigas’s first two pregnancies clearly illustrate the need for a predictive test for preeclampsia, a hypertensive condition during pregnancy that is a major cause of preterm deliveries. Both times she suffered from severe preeclampsia. Her first pregnancy ended with the death of her daughter because the condition was not recognized in time. In her second pregnancy, she and her doctors were vigilant for the first signs of preeclampsia. Even though they couldn’t prevent it, they were able to delay its onset and safely deliver her son Jordan, who is now a bright, healthy 14-year-old.

Preeclampsia At A Glance

Definition: Hypertension and excess protein in urine (proteinuria) after week 20 of pregnancy; early onset is usually considered to be before week 34; mild preeclampsia is considered to be a blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg; severe preeclampsia is defined as systolic blood pressure >160 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure >110 mm Hg; for women with preexisting chronic hypertension preeclampsia is indicated if the systolic pressure increases by 30 mm Hg or the diastolic pressure increases by 15 mm Hg

Signs & symptoms: Hypertension, proteinuria, edema (swelling), headache, nausea or vomiting, sudden weight gain, vision problems

Can lead to: Strokes, seizures, organ failure, death for the mother; growth restriction, prematurity, death for the child

Incidence: Affects 3–5% of pregnancies; 0.5% of pregnancies are affected by severe early onset

Treatment: No known treatment, but administration of low-dose aspirin starting before week 16 shows promise as a way to delay onset; regular monitoring, either at home or in the hospital depending on the severity of the preeclampsia, can be used to prolong the pregnancy

Tsigas, now executive director of the Preeclampsia Foundation, often hears the refrain “If only I’d known…” from other women who have suffered from preeclampsia. With advance warning, these women would have known to see their doctors more frequently and to monitor their own health more closely.

In the absence of a predictive test, physicians have to rely on other factors to tell them which women are at risk. Factors such as obesity, chronic hypertension, diabetes, and age increase a woman’s risk. The single biggest risk factor is preeclampsia in a previous pregnancy, but preeclampsia is most often seen in first pregnancies. That paradox is the main reason that a biochemical test is needed.

Had a predictive test for preeclampsia existed, Tsigas and her physicians could have been aware early in her first pregnancy of what was in store for her and could have taken steps to reduce the impact. Several companies are on a quest to identify biomarkers that they can turn into such predictive tests and diagnostic tests, which are also needed. Some tests have already been launched; others are on the way.

Preeclampsia is a syndrome typically defined as hypertension and excess protein in the urine (proteinuria) after week 20 of pregnancy. The challenge in diagnosing preeclampsia is that the clinical signs are nonspecific. Elevated blood pressure and proteinuria can indicate any of a number of conditions. Early-onset preeclampsia is usually considered to begin before week 34 of the approximately 40 weeks that characterizes full-term pregnancy. In severe preeclampsia, the mother can experience strokes, seizures, organ failure, and even death. Eclampsia is a related life-threatening condition that is characterized by epileptic-like seizures. In rare instances, a woman can develop postpartum preeclampsia, which strikes anywhere from 48 hours to six weeks after delivery.

Preeclampsia is estimated to occur in 3 to 5% of all pregnancies, with severe early-onset preeclampsia occurring in about 0.5% of pregnancies. “Next to postpartum hemorrhage, it’s the number-two reason for maternal death in the world,” says Garrett Lam, an obstetrician/gynecologist and maternal fetal medicine specialist at the University of Tennessee College of Medicine in Chattanooga.

Once a woman progresses to severe preeclampsia, the only known treatment is to deliver the baby. Many cases of preeclampsia thus lead to preterm delivery, which in turn means an expensive stay in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and the possibility of long-term disabilities.

The causes of preeclampsia are unclear. Scientists have the best idea of the factors involved in early-onset preeclampsia.

“We know early-onset preeclampsia is essentially a placental disease,” says Jenny Myers, a researcher at the Maternal & Fetal Health Research Center at the University of Manchester, in England. “We know there’s something that goes wrong quite early in the pregnancy.” Most of the biomarkers Myers and her colleagues have been looking at to predict early-onset preeclampsia originate from the placenta, she says.

The best results for delaying the onset of preeclampsia have been obtained with women at high risk of developing the condition who started taking low-dose aspirin before week 16 of their pregnancy. This success supports the need for an early predictive test.

But despite being the only available preventive option, low-dose aspirin is not particularly effective, and there are disagreements in the medical community about its usefulness.

“Because we don’t have a really good way of identifying women who are at the highest risk of developing preeclampsia, we can’t test more controversial treatments,” Myers says. That’s because researchers don’t want to give medications to pregnant women without having a good way to identify women likely to benefit from them and to assess the risks and benefits.

If a woman suffers from preeclampsia in her first pregnancy, she is immediately deemed at high risk for preeclampsia in any subsequent pregnancy. That’s why Tsigas and her doctors were prepared when she was pregnant again. She took low-dose aspirin and checked her blood pressure at home. At the first sign of preeclampsia, Tsigas was hospitalized and she and her baby were closely monitored for almost two weeks to determine when to deliver the baby. The goal was to extend the pregnancy to the point that neither of them was deriving additional benefit. As a result of this course of treatment, the baby was spared long-term disabilities that can accompany premature delivery, even though he still did have to spend time in the NICU.

Tsigas’s second preeclampsia experience thus had a happy ending. However, “women shouldn’t have to suffer a traumatic first pregnancy to learn how we need to be cared for in a subsequent pregnancy,” she says.

Several companies are working on molecular tests that can predict early in a pregnancy a woman’s likelihood of developing preeclampsia. Two such tests are already on the market and others are on the way. Other companies are working on tests to confirm a diagnosis of preeclampsia.

The most common marker used in confirmatory tests is placental growth factor (PlGF). Many of the early-onset cases can be traced back to problems with the placenta that result in low levels of PlGF.

In one such test, the Alere Triage PLGF Test, PlGF levels are measured in the plasma of women with suspected preeclampsia.

“In a normal healthy pregnancy the PlGF level will increase from the beginning of the pregnancy up until week 32. It will plateau about week 32, and then it will start to fall quite quickly until delivery,” says Paul Sheard, program director for women’s health at Alere. “In women with preeclampsia, or likely to develop preeclampsia, levels of PlGF will be much lower.”

In Alere’s test, PlGF levels in plasma lower than 12 pg/mL indicate that a woman is likely to deliver preterm, whereas levels above 100 pg/mL indicate that she is very unlikely to deliver in the next two weeks. The test has been validated for use up to week 35 of pregnancy, Sheard says.

Such diagnostic tests can confirm that a woman has preeclampsia and that the need for action is imminent. Predictive tests, in contrast, could give women and their doctors an early warning that allows them to take steps to prolong the pregnancy without threatening the life of either the mother or the child.

The Screening for Pregnancy Endpoints (SCOPE) Consortium has established a biobank of samples from approximately 6,000 pregnant women in the U.K., Australia, New Zealand, and Ireland. The consortium has focused on healthy, low-risk women in their first pregnancy. Samples from this study are being used to help develop predictive tests.

“They’re the women for whom we all feel a biochemical screening test would be most valuable because they don’t have the previous pregnancy to guide us,” Myers says. She is one of the researchers involved in SCOPE.

Predictive tests were launched earlier this year by Thermo Fisher Scientific and PerkinElmer, both of which use a similar set of biomarkers.

Both tests combine fluorescent immunoassays of PlGF, PAPP-A (pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A), and AFP (α-fetoprotein) with physical measurements of mean arterial pressure (a measurement of blood pressure) and of circulation through the placenta (a test called the uterine artery Doppler pulsatility index, which is measured via ultrasound). The biochemical and physical measurements are considered with information on a patient’s clinical risk factors to calculate a risk score.

Both tests are meant to be used at the end of the first trimester, approximately between weeks 10 and 14. “When we give a risk for preeclampsia, it’s a risk that the mother is going to develop preeclampsia that results in delivery before 34 weeks,” says Jonathan B. Carmichael, director of bioassay development and clinical laboratory at PerkinElmer Labs/NTD in Melville, N.Y. Delivery before then is most likely to result in adverse outcomes.

The biggest difference between the two tests is in how they are being marketed. Thermo Fisher is selling the test as a kit to be run on its Kryptor clinical analyzers, says Bruno Darbouret, head of R&D in the biomarkers business unit of Thermo Fisher. The kit is not yet approved for use in the U.S. PerkinElmer’s test is also being offered outside the U.S. as a kit, but it’s available in the U.S. as a clinical testing service performed by PerkinElmer Labs/NTD.

Other biomarkers are also in development for prediction of preeclampsia. Companies are willing to talk about some aspects of these development programs, but none will reveal the full range of biomarkers they are considering.

Pronota, a company in Ghent, Belgium, is working on a predictive test that will be administered halfway through a pregnancy, at week 20. “We’re focused on all first pregnancies,” says Katleen Verleysen, chief executive officer of Pronota.

They have chosen the 20-week mark because they think some factors that contribute to preeclampsia can’t be fully recognized until the second trimester. In addition, Verleysen says, week 20 coincides with an important visit for pregnant women in which the standard ultrasound test is performed, when most women would be seeing their doctor anyway.

“Preeclampsia can happen as early as 24 weeks, but on average it’s diagnosed around 28 or 30 weeks of gestation,” Verleysen says. “Our test would be eight to 10 weeks before the majority of cases are diagnosed.”

The test uses a panel of four protein biomarkers. The lead biomarker is the acid labile subunit of insulin-like growth factor, also called ALS. The company has not disclosed the other three markers. ALS performs well for risk evaluation on its own, but the other biomarkers help catch additional cases. “We really want the best possible performance, so we added some additional proteins and an algorithm on top of that to make sure we cover the majority of the cases,” Verleysen says.

The markers were identified by using mass spectrometry to dig into the proteins in blood samples from the SCOPE study. “We looked at as many proteins in blood as we possibly could, and then we compared women who developed preeclampsia with women who didn’t develop preeclampsia,” Verleysen says. They validated the markers in two other studies and then translated the test to an immunoassay and confirmed the results yet again.

Pronota anticipates launching the test as a clinical lab test in the U.S. in early 2015. In parallel with that launch, the company plans to conduct the necessary trials to obtain approval from the U.S. Food & Drug Administration to sell the test as an in vitro diagnostic kit for other labs to perform. The business model will be different in Europe. There the company plans to offer nonexclusive licenses to major players in the field of in vitro diagnostics.

At Carmenta Bioscience, based in Palo Alto, Calif., “we weren’t dogmatic about finding particular markers” for preeclampsia, says cofounder and CEO Matthew Cooper. Instead, the company uses systems biology, which is the study of how interactions between components of biological systems give rise to function, to ask unbiased questions about which markers are important in preeclampsia.

“Our research produced a panel of six markers that captures the complexity of the disease,” Cooper says. Carmenta is still waiting for patents, so Cooper is unwilling to identify the markers, but he notes that the panel contains proteins involved in placental tissue damage, oxidative stress, renal function, and inflammation.

Some of the markers behave similarly in different types of preeclampsia and others are variable. “We don’t have enough empirical data yet to put a stake in the ground and say that if you have this behavior in your markers then you have this kind of preeclampsia or that kind of preeclampsia,” Cooper says. However, he believes the company will have that empirical data within the next six months.

Advertisement

In the meantime, Carmenta is working on two tests—a confirmatory test for symptomatic women and a predictive test for asymptomatic women. The confirmatory test is in clinical validity trials, which should be finished by the end of the year. The timeline for the predictive test is longer. Assuming the ongoing trials are successful, the company plans to take the test to market as a clinical lab test. But the company hopes to retain the option of migrating to FDA-approved kits later on.

Proteins aren’t the only potential molecular markers of preeclampsia. The company Metabolomic Diagnostics, based in Cork, Ireland, has used samples from the SCOPE study to identify metabolites for a predictive test.

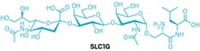

The biomarkers were discovered by using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to analyze plasma samples from 60 women who went on to develop preeclampsia and 60 matched controls. The researchers found a set of 45 relevant metabolites in 11 chemical classes (Hypertension 2010, DOI: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.110.157297). Of those 45 metabolites, 14 were identified as providing the most robust predictive model. They include amino acids, carbohydrates, fatty acids, lipids, phospholipids, and steroids.

Those 14 metabolites are the starting point for the company’s predictive test, says Robin Tuytten, vice president for R&D at the company. “We’re refining this panel to arrive at the minimal robust set,” he says. “If some of the biomarkers turn out not to work well in routine analysis, we have other candidates that can replace them.”

Metabolomic Diagnostics is currently focusing on week 15. From there, the company might shift earlier or later, but such changes could require a different mix of metabolites. “Metabolites are quite dynamic, and pregnancy as a process is quite dynamic,” Tuytten says. “A biomarker that is relevant at week nine might not be a biomarker anymore at week 16. If you map markers over gestation, you see them going up and down. They might have aberrant behavior only at certain times in the pregnancy.”

Like Pronota and Carmenta, Metabolomic Diagnostics also plans to launch clinical lab tests first. “We would like to bring something to market in 2015,” Tuytten says.

Tsigas’s organization, the Preeclampsia Foundation, advocates for patient education about the condition and for the development of predictive and diagnostic biomarkers. The foundation has convened a consortium of companies to advance biomarker development.

“The bottom line to any of these biomarkers is empowering women to be in partnership with their health care providers to make informed decisions,” Tsigas says. “That’s why we advocate for patient education around preeclampsia and its signs and symptoms during prenatal care.”

As great as the impact of a predictive test could be in the developed world, it could have even greater importance in the developing world. According to Myers, “In countries with good antenatal care, the number of women who go on to have eclamptic seizures is very small.” At St. Mary’s Hospital in Manchester, where she works, “we only have four or five women in our hospital with eclamptic seizures every year,” Myers says. However, “in Bangladesh, a hospital that has half the number of women we deliver a year will have five or six women with eclampsia a day.” Many of those women die. “If we had a better way of identifying those women, we would really be making a huge difference.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter