Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Protection From Poisonous Gold

Microbiology: Bacteria secrete a peptide to shield against the metal’s toxicity

by Sarah Everts

February 8, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 6

\

\

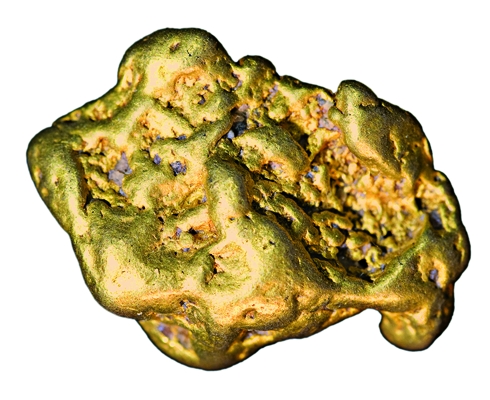

Delftibactin helps some bacteria survive contact with gold.

Living in a gold home sounds like it could be a fabulous housing arrangement. But for microbes that take up residence on gold, the precious metal can be toxic.

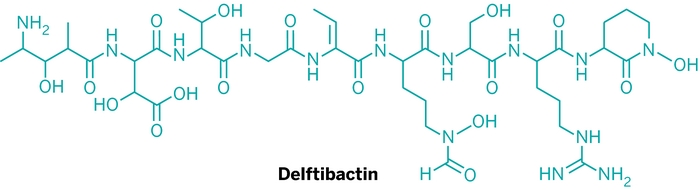

This is why bacteria called Delftia acidovorans produce and secrete an unusual peptide called delftibactin. Researchers in Canada have just reported that the newly identified molecule helps these bacteria survive by sequestering toxic forms of soluble gold (Nat. Chem. Biol., DOI: 10.1038/nchembio.1179).

This is “the first demonstration that a secreted metabolite can protect against toxic gold and cause biomineralization,” notes Nathan A. Magarvey, a biochemist at McMaster University, in Hamilton, Ontario, who led the research. Magarvey hopes to develop the peptide so it can be used to build gold nanoparticles of defined sizes for use in biomedical applications, such as cancer therapy. If the molecule is found to be selective enough for gold over other metals, it may also be employed in gold recovery.

Although D. acidovorans is sometimes found in gold biofilms, a more common species of gold-residing bacteria is Cupriavidus metallidurans, comments Dietrich H. Nies, a microbiologist at Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, in Germany. C. metallidurans survives the metal’s toxicity by expressing protein export pumps that kick out toxic gold compounds from the cell, resulting in gold precipitation outside bacterial cells.

The new study on D. acidovorans “is excellent, as it shows how different organisms living in biofilms on gold grains have different strategies of dealing with gold toxicity,” comments Frank Reith, a geomicrobiologist at the University of Adelaide, in Australia. These strategies increase a biofilm’s potential to adapt to different environmental conditions, he says.

Next up, Magarvey says his team is trying to understand the mechanism by which delftibactin chelates gold and what other metals the molecule can sequester. So far the team has found that the peptide can also bind iron and gallium.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter