Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Electronic Materials

Transparent Transistors, Printed On Paper

Electronics: Researchers report first transparent paper-based transistors, which could lead to green electronics

by Katherine Bourzac

February 4, 2013

To make light-weight, inexpensive electronics using renewable materials, scientists have turned to a technology that is almost 2,000 years old: paper. In an important step toward paper-based devices, researchers report fabricating transistors on transparent, exceptionally smooth paper (ACS Nano, DOI: 10.1021/nn304407r).

Over the past five years, materials scientists have made electronic devices such as batteries and light-emitting diodes from paper. In these electronics, paper takes the place of conventional materials such as glass or plastic. Unlike those materials, paper comes from a renewable source.

Researchers can build electric connections on paper because the material readily absorbs inks, whether those inks contain pigments used to print the newspaper or electronic materials like carbon nanotubes and semiconducting polymers. Materials scientists envision fabricating circuits like publishers print periodicals.

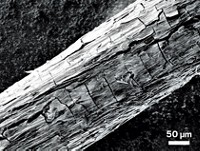

But to make paper-based circuits that can perform calculations or control displays, researchers need to find a way to print transistors. Unfortunately, previous paper transistors perform poorly because the surface of regular paper is bumpy and uneven. For a transistor to perform optimally, electrons have to move easily through super thin layers of conducting and semiconducting materials. These layers are only a couple hundred nanometers thick, while the bumps on the surface of regular paper are tens of micrometers tall. The paper bumps disrupt the flat layers of electronic materials and interrupt the device’s electron flow.

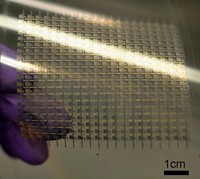

In addition to its rough surface, regular paper’s other limitation is its opaqueness. To produce electronics for transparent displays, researchers need a transparent material, like plastic or glass.

So for printed transistors, Liangbing Hu, a materials scientist at the University of Maryland, College Park, turned to a smooth and transparent kind of paper called nanopaper. Instead of the micrometer-sized cellulose fibers found in regular paper, sheets of this material contain nanoscale fibers that produce an even surface and allow light to pass through.

Hu’s group made their own nanopaper using previously reported methods, which involve treating paper pulp with oxidizing chemicals. The nanopaper has cellulose fibers with an average diameter of 10 nm. “It’s as flat as plastic,” Hu says.

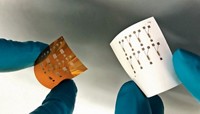

The Maryland researchers then built transistors on the paper by depositing a layer each of three materials: first carbon nanotubes, next an insulating organic molecule, and then a semiconducting organic molecule. To complete the device, the team topped it with electrodes, also made by laying down carbon nanotubes. Besides serving as electrodes for the transistors, the nanotubes provided a structural backbone, preventing excessive wrinkling in the paper after the solvents used in the fabrication process evaporated.

The resulting transistors are about 84% transparent, and their performance decreases only slightly when bent. Still, Hu says the performance of these first transistors is not optimal. He thinks decreasing wrinkling in the nanopaper will improve the devices.

Jeffrey Youngblood, a materials engineer at Purdue University, calls these nanopaper-based transistors “another step down the road to renewable printed electronics.” For such devices to be practical, he says, the researchers will have to find a way to produce the transistors via a scalable process, such as roll-to-roll printing, instead of the tedious layer-by-layer process described in the report.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter