Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Lighting Up The Golgi Of Cancer Cells

Cancer Diagnosis: Fluorescent probe glows upon binding an enzyme that accumulates in the Golgi apparatus of cancer cells

by Laura Cassiday

August 7, 2013

A new fluorescent probe offers a way to distinguish cancer cells from healthy cells by lighting up a key cellular structure called the Golgi apparatus (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, DOI: 10.1021/ja4056905). The new probe could be a tool for early cancer diagnosis or for guiding tumor surgery. It could also help scientists understand changes in cancer cells as they die, a potential way of evaluating the effectiveness of cancer drugs or other therapies.

Although earlier cancer diagnoses lead to better outcomes, “accurate early diagnosis is difficult, especially in a cheap and simple way,” says Xiaojun Peng at the Dalian University of Technology, in China. The problem is that at early stages of the disease, cancer cells are relatively rare and difficult to detect. Some researchers think fluorescence microscopy imaging could be a good way to pick out the cancer cells. However, the fluorescent probes developed thus far cannot penetrate into specific organelles involved in cancer processes.

Peng, Jiangli Fan, and their coworkers designed a fluorescent probe that can get inside the Golgi apparatus. The Golgi modifies, transports, and secretes proteins once they come off the cell’s protein synthesis machinery. Cancer cells often overproduce certain proteins such as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and the proteins accumulate in the Golgi. Scientists think that this protein buildup could trigger cell suicide, but they don’t know the precise timing and mechanisms involved. The team’s probe can detect this buildup of COX-2.

To make their probe, the researchers connected indomethacin, an inhibitor of COX-2, to a fluorescent dye, acenaphtho[1,2-b]quinoxaline, via a flexible hydrocarbon linker. Peng and Fan designed the probe with a suitable molecular weight and balance of hydrophilic and lipophilic groups that enable it to cross the Golgi’s membrane and enter the organelle.

In the absence of COX-2, the molecule folds up so that the indomethacin sits on top of the dye and quenches its fluorescence through a process called photoinduced electron transfer. However, when indomethacin binds to COX-2, the probe unfolds and the dye can fluoresce, glowing green when hit with 800-nm light.

Peng and Fan used fluorescence microscopy imaging and flow cytometry to show that the probe lit up two cancer cell lines but not two normal cell lines. The probe also lit up slices of sarcoma tissue from mice but not healthy liver tissue.

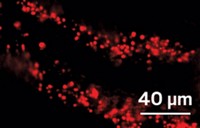

Using fluorescence microcopy, the team confirmed that the probe slipped inside the Golgi apparatus, which they stained red. In six cancer cell lines tested, the researchers could see that the COX-2 probe preferentially accumulated in the Golgi apparatus. Moreover, the COX-2 probe allowed the researchers to track the green glow of the enzyme as it spilled out of the Golgi apparatus, which breaks apart during apoptosis.

Richard W. Horobin at the University of Glasgow says that the new probe employs a smart trick of undergoing a dramatic conformational change when it binds COX-2. This change produces a large difference in fluorescence intensity between the “on” and “off” states of the probe. He thinks the ability to image COX-2 within a single organelle makes the approach “potentially more than just a simple yes/no diagnostic.” For example, observing changes in COX-2 accumulation in the Golgi could give insights into the processes involved in cancer cell apoptosis and help explain how some cancer cells can evade this process. It will be interesting to see if the COX-2 probe works in a wider variety of cancer cell lines, he adds.

In addition to potential diagnostic applications, the probe might be used to guide tumor resection during surgery, Peng says. Doctors could spray the probe on cancerous tissue and look for the glow to know where to cut. However, he notes that the probe will most likely need to be modified and improved before it is ready for clinical applications. His team has started testing the probe in animals.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter