Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Made-To-Order Branched Proteins

Protein Engineering: Researchers build unique protein shapes with the help of genetically encoded peptide tags

by Louisa Dalton

September 4, 2013

Cells usually build proteins in strings that then fold up into three-dimensional shapes. Some protein engineers, however, would like to construct proteins that branch like synthetic polymers do. These new protein shapes could lead to novel biomaterials with applications such as drug delivery or encapsulating cells in tissue engineering.

Now chemists demonstrate that simple, genetically encoded tags can make proteins branch in a variety of shapes (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, DOI: 10.1021/ja4076452).

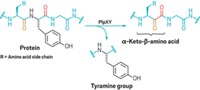

The team, led by Frances H. Arnold and David A. Tirrell at California Institute of Technology, read about the tags in a 2012 paper (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1115485109). A British group produced the tags from a bacterial protein that forms an unusual bond, called an isopeptide bond, between the side chains of a lysine and an aspartate. They split the gene for the protein in two so that, when translated, one peptide contained the lysine and another had the aspartate. When mixed, the two peptides, called SpyTag and SpyCatcher, link up, forming the isopeptide bond in minutes. The two tags can be inserted into the genes of separate proteins and act like a dab of protein cement to connect the biomolecules.

The Caltech group quickly saw the potential to build unique protein shapes by placing the tags in different positions in a protein chain. For example, the team made tadpole-like shapes by inserting SpyCatcher at one end of an engineered peptide and SpyTag in the middle of the same chain. So far, they’ve made circles, stars, and H-shapes. The branching reactions are simple and efficient, the researchers say, occurring spontaneously in water or living cells without external catalysts.

The tags, Tirrell says, provide “a way to get beyond linear proteins and take advantage of various branching phenomena that have been used to such good effect in polymer chemistry.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter