Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Role Of Folded DNA Revealed

ACS Meeting News: Study shows i-motifs and related hairpins activate or repress gene expression

by Stu Borman

March 21, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 12

The human genome is sprinkled throughout with mysterious folded DNA structures known as i-motifs. At last week’s American Chemical Society meeting in Dallas, scientists reported a long-awaited role for these structures, along with closely related hairpinlike ones: i-Motifs activate gene expression, and the hairpins repress it.

The scientists developed small molecules targeting each of these structures and used them to unravel the molecular mechanism of the gene activation and repression process. The findings suggest such molecules could be used to make cancer cells more vulnerable to existing therapeutics.

The researchers concluded that i-motifs and related hairpins are a promising new class of drug targets—not only for treating cancer but potentially for other therapeutic indications as well.

The work was carried out by pharmaceutical sciences professor Laurence H. Hurley and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopist Danzhou Yang of the University of Arizona, professor of chemistry and biochemistry Sidney M. Hecht of Arizona State University, bioanalytical chemist Hanbin Mao of Kent State University, and coworkers. Hurley and Mao reported on the work in a Division of Medicinal Chemistry symposium. The team also describes it in three recent papers (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, DOI: 10.1021/ja410934b and 10.1021/ja4109352; Nucl. Acids Res. 2014, DOI: 10.1093/nar/gku185).

“It’s the sort of evidence we’ve been waiting for,” said i-motif expert John A. Brazier of England’s University of Reading, in that the role of i-motifs had been suspected but not confirmed. “I’m really quite gutted because we were hoping to publish on the first small molecule to stabilize an i-motif, but they beat us to it.”

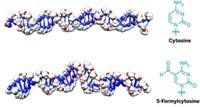

i-Motifs are kissing cousins to G-quadruplexes, folded genomic DNA structures that are already known to control gene expression, which has made them targets of ongoing drug discovery efforts. G-quadruplexes are cubelike conformations that form in single strands of genomic DNA. In the same genomic locations, complementary single strands can form i-motifs, which resemble bent, cross-linked paper clips. The i-motifs exist in equilibrium with more-flexible hairpins.

The team identified a piperidine derivative (called IMC-48) and a pregnanol derivative (IMC-76) that modulate gene expression by interacting with i-motifs or corresponding hairpins. Binding and stabilizing i-motifs or hairpins switches gene expression on or off, respectively.

The mechanism by which these structures control gene expression became apparent when the researchers used the small molecules in cancer cells with overactive BCL2, a gene that is overexpressed in cancer. They found that an endogenous transcription factor called hnRNP LL recognizes and binds to an i-motif in BCL2, activating gene transcription. But it doesn’t recognize the flexible hairpin structure. Using IMC-76 to stabilize the hairpin thus turns off gene expression, making the cancer cells more susceptible to the chemotherapy drug etoposide, the study shows.

The approach has been patented and licensed for further development to TetraGene, in Salt Lake City, a start-up Hurley cofounded.

“Can we see this equilibrium in other i-motif-forming sequences” and thus potentially extend the approach to other medical conditions, besides cancer? Brazier asked. “That would be the next step.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter