Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Careers

Rethinking U.S. Science Education

Reorganization of federal education programs is under way, but the upshot of this Obama Administration effort is unclear

by Andrea Widener

June 30, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 26

A year after sweeping reform was almost universally panned, the Obama Administration is pushing forward with a scaled-back reorganization of federal science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education programs.

The Administration abandoned its initial reorganization plan that would have cut more than 100 programs and shifted money among agencies after a barrage of criticism. It would have made these changes largely without input from those concerned about STEM education—or, in some cases, from the agencies themselves.

The newest reorganization plan still eliminates dozens of STEM education programs. But it gives agencies more control over which programs survive.

At the same time, the White House Office of Science & Technology Policy (OSTP) is pushing ahead with a five-year strategic plan designed to improve coordination among federal agencies and focus their efforts on a few STEM education goals.

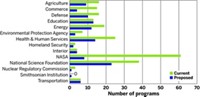

SOURCE: “Progress Report on Coordinating Federal Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Education,” White House Office of Science & Technology PolicyA five-year planb for federal science education reform has resulted in a reduction in the number of programs across federal science agencies. Here are a few prominent examples.

The Administration clearly has a goal of improving federal STEM education programs and is showing that through its proposals and an increased budget request to Congress, says James Brown, director of the STEM Education Coalition. That group represents 500 business, science, and educational organizations, including C&EN’s publisher, the American Chemical Society. “The Administration has put more skin in the game in terms of making STEM a budget priority,” he says, proposing $2.9 billion for 2015, up 3.7% from 2014 levels.

But for the STEM education community, the end result of all this change is still sketchy. The Administration’s current reorganization proposal cuts many programs, but the reasons for targeting these affected programs and not others are unknown. Also a mystery is exactly how coordination between federal agencies will play out for local schools and individual scientists and educators.

“The plan is at such a high level that actually saying what impact it will have is difficult,” says Helen R. Quinn, chair of the National Research Council’s (NRC) Board on Science Education.

Through the years, federal STEM education programs have been created piecemeal by individual agencies. Meanwhile, educators, businesses, academics, and science organizations have called for more federal coordination. As part of the 2010 America Competes Reauthorization Act, Congress ordered OSTP to examine how it manages STEM programs.

In response, the Administration spent a few years figuring out what STEM education efforts existed and plotting a way to ensure that federal dollars were being spent on effective programs.

In 2013, government officials unveiled the five-year strategic plan. It lays out five goals: improvements in teacher training, increases in public and youth engagement, enhancements in undergraduate education, increases in the number of underrepresented minorities and women in science, and reforms in graduate education.

But the strategic plan was overshadowed by the controversial STEM reorganization proposal, which had come out a few weeks earlier. In addition to eliminating many programs that those lobbying on behalf of STEM education had backed, the reorganization placed coordination for K–12 STEM education in the hands of the Department of Education, which had virtually no STEM expertise. The plan also put informal education under the control of the Smithsonian Institution, which is best known for its museums.

Congress slammed the 2013 reorganization plan and ordered the Administration to go back to the drawing board.

The scaled-back reorganization that the Administration put forward this year still focuses on streamlining federal STEM education programs. But now, each agency is responsible for consolidation of programs under its purview. Many of these changes don’t require approval from Congress.

“Overall, the changes are not very transparent,” Brown says. “It is not clear to me what actions the individual agencies have done in terms of consolidating.”

According to federal data, the National Aeronautics & Space Administration has seen the most cuts in STEM education programs, dropping from 61 in 2012 to just eight in the proposed 2015 budget. The agency realized several years ago that its education programs weren’t focused or coordinated and made a conscious effort to change, says Shelley Canright, senior adviser at NASA’s Office of Education. In 2011, NASA started warning programs about upcoming cuts and has gradually phased out many programs.

“Something will have to sunset to have something new start” given dwindling federal dollars, she says. NASA did not end any program earlier than the agency had planned. The agency’s new STEM education programs are more sharply focused on the goals set out in the five-year plan, Canright says, especially on broadening participation of minorities and women in science.

NASA is also participating in the five-year strategic planning process, which for the first time has brought together the 13 federal agencies that work on STEM education. Newly created committees oversee each of the five goals, and agencies are sharing in detail what they are doing.

“I’m hearing a lot of excitement from the folks on these committees,” says Joan Ferrini-Mundy, the National Science Foundation’s assistant director for education and human resources. “These are quite rich discussions.”

Going forward, the agencies will create common goals and measures of success for their educational programs as part of the five-year plan, explains Ferrini-Mundy, who is helping lead the process. “There is quite a lot of work to do,” she says.

The STEM education community still has a lot of unanswered questions about where the federal effort is leading. OSTP held one meeting with education stakeholders shortly after the 2015 budget was first released in March, but there hasn’t been an ongoing discussion about federal STEM education’s future. Brown wants to see a more open dialogue about the federal government’s role in STEM education. “We would like to see a broader conversation about evidence and what is actually working,” he says.

Questions surround the role of the Smithsonian Institution and the Department of Education, which in many ways were outside of the STEM education communities when they were chosen last year as leaders in the reorganized federal effort. They retain these roles in the Administration’s revised plan.

The Smithsonian is to oversee informal STEM education programs, which would be a new role for the institution. But the Smithsonian has yet to receive any funding for these activities. “I can say with some confidence that there is not a plan within the government for how to consolidate informal education” at the Smithsonian, says Brown of the STEM Education Coalition.

The Department of Education’s role overseeing K–12 education makes it a more natural fit because of its broad reach to state educators. But the department has historically had few ties to the science education community. In the past year, it has brought on more STEM education staff to create a team for this area, says Camsie McAdams, the team’s deputy director. In addition, the department is working to incorporate STEM into more of its existing programs. McAdams says that 60 competitive awards in the past three years have included STEM among their criteria.

One question is whether the Department of Education’s STEM funding should be given to states primarily through competitions or whether every state should get some dedicated STEM funding. “Most stakeholders agree that we should have some sort of foundational grants that keep everybody in the game,” she says. “Beyond that, we should be doing a better job of taking great ideas and either replicating them or scaling them up or proving that they work elsewhere.”

Others wonder how the recent reorganization or the five-year plan is going to improve science education in the country. That is especially true for agencies such as NASA and the National Institutes of Health, whose primary focus is science but which have long had a hand in science education.

Quinn from the NRC board has seen that attempts at agency coordination in the past have made it harder for the average scientist or educator to improve STEM education. The new plan is “very vague” about the role of science agencies, she says, “or what they will be funded to do in the future.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter