Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Safety

Toxicity Unknown

Pollution: Lack of hazard data hampers response to chemical spill in West Virginia

by Jeff Johnson , Cheryl Hogue

January 17, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 3

A lack of toxicity data stymied officials in Charleston, W.Va., this week as they rushed to clean up the city’s contaminated drinking water system.

They ordered more than 300,000 people not to drink or wash in tap water for nearly a week after a leaking chemical storage tank poured thousands of gallons of a coal-processing liquid into the Elk River. They advised pregnant women to drink bottled water until the chemical is no longer detectable in the water system.

The leaking tank is about 1 mile upstream from the intake pipe for Charleston’s water supply system, which is the state’s largest. Freedom Industries, a chemical supplier and blender, owns the tank.

\

\

Freedom Industries’ storage tanks (top) are adjacent to the Elk River. Tank number 396 (bottom) is the one that leaked the coal-processing chemical, tainting the Charleston, W.Va., water supply.

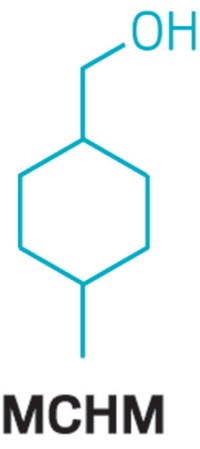

Polluting the water system was crude 4-methylcyclohexanemethanol (MCHM), which is used to clean coal for electricity-generating plants. Little is known about the hazards of the substance, a situation that left officials scrambling for answers as they faced a frightened and angry public.

“That was a new chemical for us. We never encountered it in any of our previous investigations,” says Daniel M. Horowitz, managing director of the Chemical Safety & Hazard Investigation Board. CSB began probing the incident at the urging of Sen. John D. Rockefeller IV (D-W.Va.) soon after the leak was discovered on Jan. 10.

“There is not a great deal known about MCHM’s toxicity, and that is one of the reasons this accident has been difficult,” Horowitz says. “You never want to be in the position of performing a toxicity experiment like this on your own drinking water supply.”

A 2011 material safety data sheet from Eastman Chemical, the maker of MCHM, warns that the substance is “harmful if swallowed” and “causes skin and eye irritation.” But it offers little more information, with more than two dozen entries marked “no data available.” These include inhalation effects, carcinogenicity, reproductive toxicity, biodegradability, and physical-chemical properties including evaporation rate.

The lack of toxicity data on MCHM, Horowitz says, demonstrates “a very profound point: There are literally tens of thousands of chemicals that are out there for which we don’t have complete hazard information.”

“We really need these chemical data to be available at the time something happens so that intelligent decisions can be made,” agrees Richard Denison, senior scientist with the Environmental Defense Fund, an activist group.

But the 37-year-old federal law governing chemical production, the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), doesn’t require chemical makers to generate this information. Companies are not mandated to submit hazard information they have to the Environmental Protection Agency, except when data suggest the possibility of substantial risk. Instead, TSCA sets up complex legal requirements that EPA must meet before the agency can require manufacturers to provide toxicity data for a chemical in commerce.

The MCHM incident marks the third major chemical industry accident near the West Virginia capital that CSB has investigated in the past six years, Horowitz says. In 2010, a worker died at the DuPont chemical manufacturing plant in Belle, W.Va., east of Charleston, when three accidents, one involving phosgene, occurred within 33 hours. In 2008, two workers were killed by a blast at the Bayer CropScience plant in Institute, W.Va., west of the capital, and some 40,000 nearby residents were ordered to shelter in place.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter