Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano, And Shuji Nakamura Win 2014 Nobel Prize In Physics

Awards: Three honored for developing blue light-emitting diodes, which made possible cheap, efficient white light

by Elizabeth K. Wilson

October 9, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 41

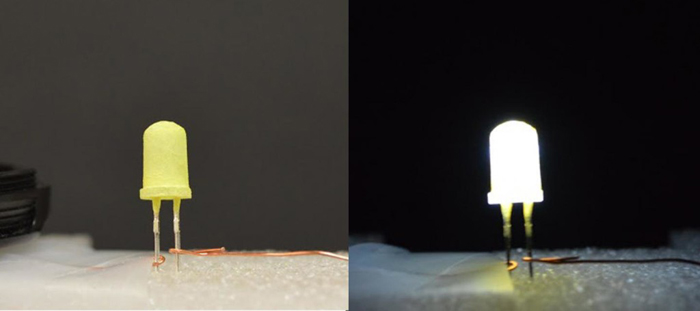

The 2014 Nobel Prize in physics honors the inventors of blue light-emitting diodes (LEDs), which have made possible inexpensive, efficient white light for a variety of applications.

Isamu Akasaki, at Meijo University, in Nagoya, and Nagoya University, both in Japan; Hiroshi Amano, at Nagoya University; and Shuji Nakamura, at the University of California, Santa Barbara, will share the $1.1 million prize.

White LED light is produced from a combination of red, green, and blue diodes. Red and green LEDs were fabricated in the 1960s. But blue light-emitting LEDs weren’t invented until the 1990s.

“The blue LED is a fundamental invention that is rapidly changing the way we bring light to every corner of the home, the street, and the workplace—a practical invention that comes from a fundamental understanding of physics in the solid state,” says H. Frederick Dylla, the executive director and CEO of the American Institute of Physics.

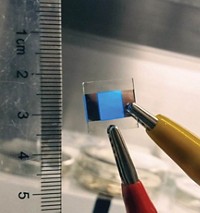

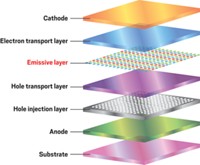

LEDs are layered semiconducting devices in which a layer of one semiconductor is sandwiched between a layer doped with electrons and another with electron holes. Electrons and holes combining in the middle layer produce photons.

A major roadblock to blue LED development involved the fabrication of suitable crystals of semiconductors, with gallium nitride being the most promising contender. The task vexed scientists for years.

“As the wavelength of the emitted light from an LED gets shorter as you move from red to green to blue and on to the ultraviolet, the sensitivity to very low levels of impurities and imperfections in the crystalline lattice becomes more acute,” Dylla says.

Akasaki, 85, worked with Amano, 54, at the University of Nagoya, while Nakamura, 60, did his research at Nichia Chemical, a small company in Tokushima. In 2000, Nakamura became a physics professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Both teams labored, and finally succeeded, in producing quality gallium nitride crystals, and improved them further with aluminum and indium alloys of gallium nitride. “They made different versions; they improved each others’ results,” said Per Delsing, a physics professor at Chalmers University of Technology, in Göteborg, Sweden, at a press conference announcing the prize.

Now everyday products including cell phones and flashlights emit white LED light. The technology is rapidly replacing inefficient incandescent light sources and mercury-containing fluorescent light sources.

It’s also been a source of some contention: A Japanese court in 2004 ordered Nakamura’s old employer, Nichia, to pay him $180 million for his role in developing commercially valuable blue LEDs.

The LED light technology is quite close to the theoretically possible ultimate efficiency of one electron-hole combination producing one photon, noted Delsing. “It will be hard to find something that will be better,” he said.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter