Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Smartphones Detect Gases On The Cheap

Sensors: Nanotube-based radio-frequency devices detect gaseous molecules, transmit data to cell phones

by Celia Henry Arnaud

December 11, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 50

Chemists at MIT have developed inexpensive chemical sensors that can be read by devices many people carry around: smartphones. Such sensors could be used to detect explosives, pollutants, or spoiled food.

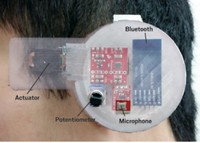

Professor Timothy M. Swager, grad student Joseph M. Azzarelli, and coworkers adapted near-field communication (NFC) tags—simple integrated circuits on plastic substrates—as chemical sensors for selective gas detection (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1415403111). The ultra-low-power requirements of their carbon-nanotube-based sensors enable the NFC tags, which are battery-free, to communicate with and be powered by cell phones via radio-frequency pulses.

To make the sensors, the researchers punch a hole in the conductive aluminum of an NFC tag’s circuit, making the tag unreadable. They then recomplete the circuit with carbon-nanotube-based materials designed to respond to specific gas molecules. In the presence of these molecules, the nanotubes change the resistance of the circuit and the resonant frequency of the tag, thus affecting the tag’s ability to communicate with cell phones. “It’s all about switching the resonant frequency in and out of tune with the cell phone,” Swager says.

The team designed each sensor to turn on or off in the presence of a particular gas. For example, one sensor stopped communicating with the cell phone in the presence of 35 ppm of ammonia. Another sensor turned on in the presence of 225 ppm of hydrogen peroxide.

“One of the cool things about using a cell phone to do this is that now you have access to big data,” Swager says. “The readings may not be as meaningful in isolation as when you get thousands of them uploaded to the Web, all with GPS coordinates.”

“The use of NFC tags as sensors is an economical idea because these tags are already mass-marketed,” says Lindsey Fiddes, a researcher at the University of Toronto who is developing wireless sensors. “The sensing tags do not require a line of sight to be read, so tags can be easily incorporated into packaging. I see it being adopted by commercial smart-packaging manufacturers as well as consumers.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter