Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Scientists Uncover New Brominated Flame Retardant In Consumer Electronics

Indoor Environment: Manufacturers may be using the compound as a replacement for toxic PBDEs

by Janet Pelley

April 4, 2014

A team of scientists using a rapid screening test have detected a new type of brominated flame retardant in homes—the first such compound found since 2008 (Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, DOI: 10.1021/es4057032). They discovered the compound in plastic electronic products made since 2012, suggesting manufacturers are using it to replace flame retardants that were phased out or banned due to toxicity issues.

Flame retardants are used in many consumer products, including electronics, clothing, and furniture, and as a result, scientists find the chemicals in outdoor air, household dust, and human blood and milk. Between 2002 and 2008, the manufacture of brominated flame retardants known as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) was banned or phased out in Europe and the U.S. after researchers linked the compounds to neurotoxic effects and disruption of hormonal signaling. “As a result of these regulations, the use of alternative flame retardants is increasing rapidly,” says Ana María Ballesteros-Gómez, an analytical environmental chemist at VU University Amsterdam.

Manufacturers don’t report the flame retardants used in consumer products, so scientists must use their best sleuthing technology to monitor new compounds introduced to the market. Some researchers have stuck with methods optimized for identifying PBDEs, but those techniques might miss compounds that have high molecular weights and low volatility. So Ballesteros-Gómez and her colleagues developed a rapid screening process that involves scratching the surface of plastic products with a probe to release fine particles of the material into the inlet of a high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometer.

To look for new compounds, she and her team went shopping for household electronics encased in hard plastic likely to contain flame retardants. They bought 13 products made since 2012, including televisions, power strips, and a vacuum cleaner. They also visited a recycling center in Amsterdam and retrieved 13 products made before 2006, when PBDEs were still in use.

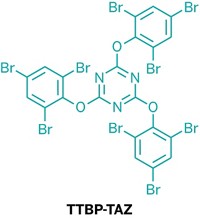

The mass spectra from the new plastics contained an unknown peak signifying a compound with nine bromine atoms. Using data analysis software, the chemists generated several potential molecular formulas for the mystery compound. The scientists then ran the formulas through several online chemical structure databases and found only one match: a triazine brominated flame retardant named 2,4,6-tris(2,4,6-tribromophenoxy)-1,3,5-triazine (TTBP-TAZ).

To confirm the match and to measure the compound’s concentrations in the plastic, the team subjected plastic samples to liquid chromatography combined with mass spectrometry. They detected TTBP-TAZ in eight of the 13 new products at levels up to 1.9% by weight of the product. Ballesteros-Gómez says the data suggest widespread use of the new compound. The researchers couldn’t find TTBP-TAZ in the old plastics. “Manufacturers may be using TTBP-TAZ to replace the banned octaBDE and decaBDE in hard plastics,” Ballesteros-Gómez says.

Because household dust is the major route of human exposure to flame retardants, the researchers visited nine Dutch homes and took dust samples directly from electronic equipment, from tables around the equipment, and from the floor. Using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry, the researchers detected TTBP-TAZ at levels between 160 and 22,150 ng per g of dust. These concentrations are lower than those reported for PBDEs and about the same as those for V6, a chlorinated organophosphate flame retardant. TTBP-TAZ is the first new brominated flame retardant found in homes since tetrabromobisphenol-A-bis-(2, 3-dibromopropylether) was detected in 2008, the researchers say.

A 2012 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency report on possible alternatives to one PBDE concluded that TTBP-TAZ has a high potential for bioaccumulation and persistence in the environment. The European Union and the U.S. does not consider the compound to be toxic, but it shares structural properties with PBDEs, says Heather M. Stapleton, an environmental chemist at Duke University. Both Stapleton and Ballesteros-Gómez conclude that more research is needed to determine if TTBP-TAZ is safe, because the toxicity issues of PBDEs weren’t fully known until scientists studied them in depth.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter