Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Small Molecules Help Reactivate Receptor Linked With Schizophrenia

Drug Discovery: In human and rat cells, the compounds restore glutamate receptor function lost through mutations linked with schizophrenia

by Deirdre Lockwood

September 9, 2014

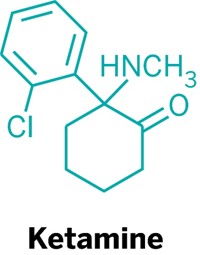

Patients with schizophrenia experience a common set of symptoms, but the biochemical causes behind those symptoms probably vary widely among those affected. Some patients with the disorder, for example, harbor mutations in genes that encode certain types of glutamate receptors in neurons.

Now, a team of researchers has developed small molecules that can restore the function of one of these malfunctioning glutamate receptors (ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, DOI: 10.1021/cb500560h). The compounds could be a first step toward personalized therapeutics for people with schizophrenia who carry these mutations.

“One person’s schizophrenia is not the same as another person’s,” says Craig W. Lindsley, director of medicinal chemistry at Vanderbilt University. This biochemical heterogeneity, he says, makes it difficult to find a single compound that could effectively treat all patients with schizophrenia.

Lindsley and his collaborators started looking for potential personalized therapeutics after reading about people in Europe and Australia with a set of 12 mutations in a glutamate receptor gene who also had a higher incidence of schizophrenia and other psychiatric diseases (PLoS One 2011, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019011; 2012, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032849). The researchers wanted to understand how these mutations affect the receptor, called metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 1, or mGlu1, and whether they could restore its function with a small molecule.

So they first expressed nine different receptors, each carrying one of the mutations, in human cells and tested the proteins’ activity. In all, the function of the glutamate receptor was disrupted. When normal glutamate receptors such as mGlu1 bind the neurotransmitter glutamate, they trigger the release of calcium inside the cells. Compared to normal receptors, the mutant ones typically released 45 to 65% less calcium in cells in response to a given dose of glutamate.

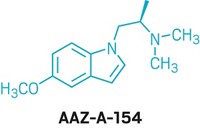

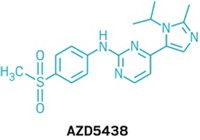

To find small molecules that could repair the mutated receptors, the researchers looked at ligands that enhance or inhibit the receptors’ activities by binding at allosteric sites on the protein. Other researchers had identified such an allosteric ligand that enhanced the activation of a similar glutamate receptor. So the team introduced two small structural changes in this ligand to adapt it for mGlu1.

They first modified an imide moiety in the original allosteric ligand. This yielded a molecule that acted on mGlu1 but inhibited the receptor’s activation rather than enhancing it. By installing a phthalimide group as the second structural change, they finally produced a molecule that enhanced mGlu1’s activation.

After preparing a set of analogs of this ligand, the team tested the analogs’ activity against the nine mutated receptors in both human and rat cells. Two compounds rescued the function of all the receptors to varying degrees. One of these compounds had promising pharmacokinetic properties and could cross the blood-brain barrier when tested in rats.

Kristin L. Bigos of the Lieber Institute for Brain Development, a research center focused on psychiatric disorders, calls the team’s results novel and impressive. As genome sequencing becomes fast and cheap enough to be applied widely, she says, treating heterogeneous diseases such as schizophrenia with personalized therapies may become more common.

Next, the team plans to test the compounds in mice expressing mutant mGlu1 to see if they can restore its function in a live animal, Lindsley says. They also want to test the compounds’ activity against mGlu1 receptors carrying multiple mutations, which are found in some people with schizophrenia.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter