Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Work Outside Of Climate Talks Seen As Key To Emissions Reductions Before 2020

Domestic and international efforts focus on curbing greenhouse gases

by Steven K. Gibb

March 30, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 13

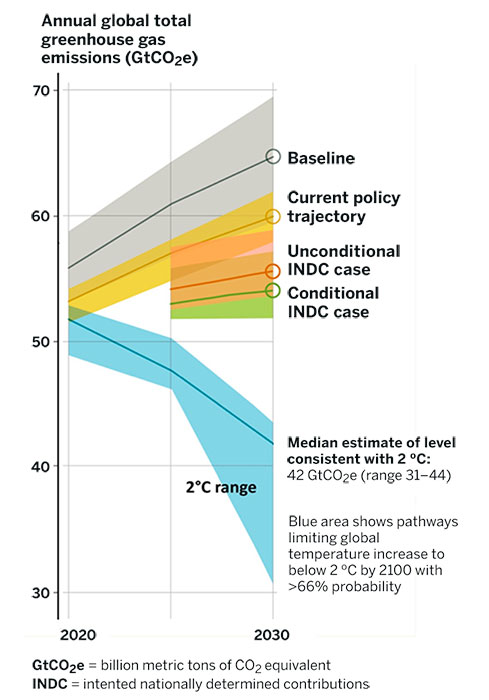

Later this year in Paris, negotiators will attempt to forge a new global pact to slow climate change. That planned treaty would not take effect until 2020. But three efforts taking place outside the formal treaty talks are paving the way for greenhouse gas emissions curbs during the next five years.

The first involves President Barack Obama. He has said he wants action on climate change to be part of his legacy as President. Facing a Republican Congress that is unlikely to pass legislation to curb greenhouse gas emissions, Obama is flexing executive branch muscle to press the issue on multiple fronts. This includes promoting renewable energy and proposing regulations to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from power plants. In addition, he has issued executive orders to cut emissions from federal operations and the government’s private-sector suppliers.

The other two efforts are international. One is the use of an existing global treaty on protecting the stratospheric ozone layer to phase out production and use of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). These chemicals are ozone-friendly refrigerants that are relatively short-lived in the atmosphere but are potent greenhouse gases. The final effort involves moves by emerging economies such as China to ratchet back air pollution, steps that can also reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

These actions contrast with past efforts to create globally coordinated action on climate that hinge on a single treaty. The last attempt in this vein faltered in 2009 at a meeting in Copenhagen, where talks stalemated and governments had to settle for a nonbinding climate change agreement.

Although countries now seem to be negotiating in earnest to have a successful outcome in Paris, governments also are pursuing short- and long-range actions outside the global talks. “You don’t want all your eggs in the Paris basket,” says Paul Bledsoe, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the U.S., a nonpartisan public policy think tank, and a former White House adviser.

As it negotiates on climate change, the Obama Administration faces intertwined challenges at home and internationally. Republican control of Congress means that other countries are unsure whether Obama can make emission control commitments that the U.S. will actually meet. In part, that’s because current congressional leaders are skeptical about or hostile to proposals to curb domestic greenhouse gas emissions. Further, the U.S. can’t become a partner to any international treaty—including the Paris accord—unless the Senate grants its advice and consent to the agreement. On top of that, the U.S., historically the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases from human activities, will be negotiating with many countries that believe the U.S. should lead the world in mitigating climate change.

These factors have led Obama to pursue executive action on climate change that doesn’t require congressional approval. Soon after his reelection in 2012, Obama began an unprecedented series of executive branch actions and regulatory efforts at the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Energy, and the Department of the Interior to reduce domestic greenhouse gas emissions and demonstrate globally that the U.S. can walk its talk on climate change.

Most recently, on March 19, the President issued an executive order that has two aims. One is to cut the federal government’s greenhouse gas emissions by 40% from 2008 levels, and the other is to increase the government’s share of electricity from renewable sources to 30%, both within a decade. In the audience when Obama announced the directive were leaders of 14 major government suppliers including Honeywell, Battelle, IBM, General Electric, and Northrop Grumman. These 14 companies are pledging to collectively cut their carbon footprint by 5 million metric tons from 2008 levels in the next 10 years.

That executive order builds on a directive Obama issued in 2009 calling for greenhouse gas reductions by federal agencies. Agencies are on track to meet the order’s reduction targets through energy retrofits and no-cost improvements in energy efficiency.

At the same time, separate talks—soon to be under way in Bangkok—have a goal of curbing emissions of HFCs. These chemicals, along with black carbon and methane, are classified as short-lived climate pollutants. The three substances stay in the atmosphere for days to decades as compared with up to centuries for carbon dioxide.

“Slowing the ‘supertanker’ of carbon dioxide emissions is an important long-term goal,” explains Durwood Zaelke, president of the Institute for Governance & Sustainable Development, a climate change mitigation advocacy group. “But we have to win the short game to give us a good shot at carbon’s long game.” Curtailing the release of short-lived greenhouse gases such as HFCs is more like slowing a steamboat, he adds.

Bledsoe says there is a growing appreciation of curbing the short-term pollutants versus long-term ones. “Both environmental officials and major political leaders are starting to understand how critical the timescale issue is,” he says.

To this end, HFCs are the focus of the upcoming April meeting in Bangkok under a treaty called the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. One priority for the meeting, Zaelke says, is to steer countries away from HFCs to other, more climate-friendly alternatives as they phase out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

This effort attempts to build on the success of the Montreal protocol. The 1989 agreement has a 98% success rate in phasing out nearly 100 compounds, including CFCs and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), and enjoys broad international support, Zaelke says. Further, a 2013 paper by Mexican scientists suggests that the slowdown in the past decade’s global warming is in part attributable to the success of the Montreal protocol, because ozone-depleting CFCs and HCFCs are also greenhouse gases (Nat. Geosci. 2013, DOI: 10.1038/ngeo1999).

Meanwhile, another key action that has the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the next five years involves emerging economies reducing harmful air pollution. Concern about the worsening urban air pollution in China and India is intensifying. For example, a recent analysis by the University of Chicago, Yale University, and Harvard University found that half of India’s population may have life spans shortened by up to three years because of breathing unhealthy air. The administration of Prime Minister Narendra Modi is likely to pay attention to that information.

Environmental scientists and economists are quick to point out the multiple benefits of tackling unhealthy air quality. Ground-level ozone, the main component of smog, is also a greenhouse gas. Plus, black carbon is a component of particulate air pollution. Opportunities for dual advantages or “cobenefits” can help governments justify taking major actions on air pollution when costs and benefits are tallied, EPA says.

Even though efforts to improve air quality and address climate change in India and China face a variety of political challenges, trends suggest that efforts to stem pollution will grow as their economies expand. As they do, more resources may become available for cleaner technology, air pollution management, and the promotion of energy efficiency to reduce demand to burn coal to generate power, observers say.

Concrete progress in these three areas—domestic U.S. emissions cuts, HFC phaseouts, and air pollution reduction—is likely to help curb the global growth of greenhouse gas emissions in the next five years. Given that the outcome of negotiations set to end in Paris in December is uncertain, these three areas could represent important initiatives in their own right.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter