Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Exploring The Molecular Basis Of “Runner’s High”

Neuroscience: Exercise-induced endocannabinoids decrease anxiety and pain perception in mice, study suggests

by Judith Lavelle

October 8, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 40

After aerobic exercise, some people experience a “runner’s high”: a feeling of euphoria and reduced anxiety along with a lessened ability to feel pain. For decades, scientists associated this with an increased level in the blood of β-endorphins, opioid peptides thought to elevate mood.

Now, German researchers have shown the brain’s endocannabinoid system—also affected by marijuana’s Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)—may play a role in producing runner’s high, at least in mice (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1514996112).

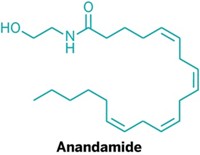

The researchers turned to the endocannabinoid system because endorphins can’t pass through the blood-brain barrier, says team member Johannes Fuss, who’s now at University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. But an endocannabinoid called anandamide—found at high levels in people’s blood after running—can reach the brain and trigger a high. “Yet no one had investigated the effects of endocannabinoids on behavior after running,” Fuss says.

The team split a group of mice into two sets: one that would run for five hours on an exercise wheel and one that would remain sedentary. Soon after their run, the rodents in the first set displayed far less anxious behavior than the sedentary set.

Similarly, mice in the running group had a higher pain tolerance than those in the sedentary group, as measured by their response to being placed on a hot plate.

Finally, the researchers performed these same experiments on mice given endocannabinoid or endorphin antagonists, which block cannabinoid and opioid receptors in the brain, respectively. The endorphin antagonists did not significantly affect results, but mice treated with endocannabinoid antagonists were still anxious and sensitive to pain despite having run for hours.

These findings suggest that endocannabinoids such as anandamide help cause runner’s high. “The authors have moved the field forward by providing such a complete view of how this key reward system is involved,” says David A. Raichlen, an expert in human brain evolution and exercise at the University of Arizona.

The researchers write that other key aspects of runner’s high, such as euphoria, are too subjective to study in a mouse model.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter