Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Takaaki Kajita And Arthur B. McDonald Win 2015 Nobel Prize In Physics

Awards: Discovery that neutrinos have mass upended subatomic physics

by Elizabeth K. Wilson

October 8, 2015

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 93, Issue 40

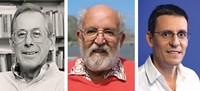

For their discoveries that the elusive but ubiquitous subatomic particles known as neutrinos have mass, Takaaki Kajita of Japan’s Super-Kamiokande and Arthur B. McDonald of Canada’s Sudbury Neutrino Observatory will receive this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics.

Kajita and McDonald led teams that performed critical experiments near the turn of the 21st century that showed that neutrinos, once thought to be massless, oscillate among three different forms, a phenomenon only possible if the particles have mass.

Neutrinos, which have no charge, are the second-most abundant particle in the universe, behind only photons. But they are so small that they can pass through Earth without interacting with anything, making their detection a monumental task.

The experiments at Super-Kamiokande and Sudbury involved enormous underground tanks filled with H2O and D2O, respectively. The liquids filtered out other heavier particles, allowing the teams to detect neutrinos streaming in from the sun and from the atmosphere. Physicists had already found that neutrinos come in three varieties, or “flavors”: electron, muon, and tau neutrinos. The flavors were thought to be intrinsic to each neutrino. But then Kajita’s and McDonald’s teams discovered that some neutrinos actually changed their flavors in wavelike oscillations.

“There was a eureka moment when [the neutrinos] appeared to change from one type to the other,” McDonald said when the prize was announced. Such oscillations could only be possible if the particles have mass.

“It was a very complex, huge engineering challenge, and they produced an extraordinary result,” says Robert G. W. Brown, CEO of the American Institute of Physics.

Although physicists know the mass differences among the three neutrinos, they still don’t know the absolute mass of each one. The upper limit for each neutrino mass is believed to be 0.2 eV, which is more than a million times as light as an electron. “The real big mystery is that we know they have mass, but we don’t understand why the masses are so small,” says Mark Thomson, professor of experimental and particle physics at the University of Cambridge and codirector of the university’s neutrino oscillation experiment.

That understanding, he tells C&EN, “may provide us a clue as to why neutrinos are special.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter