Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

DNA

FDA-Approved Drugs Boost Hair Regrowth In Mice

Hair Loss: JAK-STAT inhibitors already being used to treat autoimmune disorders prompt hair follicles to reboot their growth cycles

by Judith Lavelle

October 26, 2015

Although the idea of going bald typically conjures images of aging men, hair loss affects people of all genders and ages: Hair can fall out prematurely because of genetic predisposition, stress, drug side effects, or autoimmune disorders. A recent test of two FDA-approved drugs—ruxolitinib and tofacitinib—now suggests that a general treatment for all these hair loss conditions might be on the way (Sci. Adv. 2015, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1500973).

A team of researchers at Columbia University had observed that these drugs—approved for the treatment of myelofibrosis and rheumatoid arthritis, respectively—promoted hair growth when fed to mice but also impaired the animals’ immune systems. So the scientists were curious whether the compounds might work better when rubbed onto the rodents’ skin rather than when administered orally.

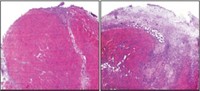

The team shaved the backs of mice at a point in the rodents’ lives when their fur was in telogen, the resting stage of a hair follicle’s growth cycle. In this stage, hair usually takes more than a month to begin growing back. But areas of a mouse’s skin treated topically with ruxolitinib or tofacitinib fully grew back in less than three weeks. Team leader Angela M. Christiano says the drugs are “basically accelerating what would normally happen several weeks later. They’re inducing new hair to begin to grow.”

The Columbia team got similar results when they tested the compounds on human skin grafted onto mice. However, in this experiment, tofacitinib was significantly more effective.

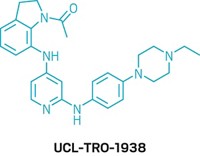

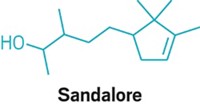

The mechanism by which these drugs spur hair growth—at least in mice—appears to be very different from standard topical hair loss treatments such as Rogaine. A therapy for male-pattern baldness, Rogaine uses the active ingredient minoxidil, a vasodilator, to stimulate blood flow to hair follicles and thereby prevent hair from falling out. In contrast, the new topical treatments inhibit JAK-STAT signaling, a pathway involving Janus kinases that triggers cells to begin transcribing DNA or undertake other activity. Researchers believe this signaling pathway is most active when hair follicles, a type of stem cell, are at rest. When ruxolitinib and tofacitinib block the pathway, the follicles “wake up” and enter a new growth phase.

“The big news of this new paper is that JAK inhibitors are even more versatile in function than previously thought,” says Amy McMichael, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, who was not involved in the study. “Not only do they have a burgeoning role in treating inflammatory conditions, but there appears to be a direct effect on stem cells that can impact hair growth function.”

Because of this direct effect, the Columbia researchers believe the treatments may be useful in hair loss caused by a variety of problems, including alopecia areata, an autoimmune disease that affects millions in the U.S., or chemotherapy-induced hair loss. “For any clinical setting where the hairs are stuck in resting phase,” Christiano says, “this would be a way to think about coaxing them back into the hair cycle.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter