Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

A Liquid Lens Could Improve Cataract Treatment

Biomedical Devices: A customizable polymer casing keeps liquid lenses clear and in place

by Prachi Patel

October 20, 2015

Every year, about 10 million patients get cataract surgery to replace the clouded crystalline lens in their eye with a clear artificial one. But these silicone or flexible plastic lenses can dislocate and cloud up again because of calcium deposits or epithelial cell growth on the lens surface. Researchers now report a liquid lens that could overcome those issues (Chem. Mater. 2015, DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b02433).

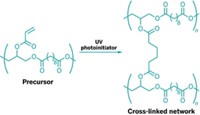

The lens is made of a liquid droplet encapsulated between two 20-μm-thick poly(p-xylylene) polymer films. These biocompatible, water-repelling polymers are approved by the Food & Drug Administration as coatings on medical implants and devices. They resist calcium buildup, and their surfaces are easy to customize using functional groups.

Hsien-Yeh Chen, a chemical engineer at National Taiwan University, and colleagues first used chemical vapor deposition to create a layer of vinyl poly(p-xylylene) on a quartz substrate. They then deposited droplets of liquids such as silicone oil and glycerol on the polymer. The liquids stick and spread on the surfaces to different extents, forming droplets of various shapes and curvatures. This should allow the lenses to be easily customized for near or far focus to accommodate patients’ differing vision prescriptions by varying the liquid composition, Chen says.

The researchers covered the droplets with another vinyl poly(p-xylylene) layer and then cut out the individual lenses along with a pair of struts. Each device is 1 mm thick and has a 6-mm-diameter liquid lens region. The researchers then attached thiol-capped polyethylene glycol molecules on the lens region to resist epithelial cell growth, and cell-attracting peptide molecules on the struts to help the lens attach more firmly to the eye’s lens sac once implanted.

The new lenses showed no cell buildup when placed in eye epithelial cell cultures for 24 hours. And they showed no calcium deposits after being immersed in calcium phosphate solutions for 48 days.

The idea of replacing cataracts with a fluid-filled lens is not new. A few research groups and small companies have been trying to develop such lenses although no products are close to medical approval yet.

The choice of vinyl poly(p-xylylene) to make a liquid eye lens is new and interesting, says Timothy Hughes, a polymeric biomaterials researcher at Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific & Industrial Research Organization. Much work is needed to validate this early-stage design, he says. For instance, it isn’t clear that the vinyl-based poly(p-xylylene) could be rolled up for insertion into the eye sac, and fat could deposit on the hydrophobic polymer. Besides, any liquid lens carries a risk of leaking, so researchers would need to do extensive safety studies in animals before doing clinical trials to gain FDA approval.

Chen says that his team plans to make the lenses more compact, characterize their mechanical properties, and investigate implantation methods before pursuing animal studies.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter