Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Imaging Agent Hits A Nerve

Bioimaging: A less toxic formulation for nerve-targeting fluorescent imaging agents could help prevent nerve damage in the operating room

by Katherine Bourzac

November 11, 2015

Nerves are small, transparent, and often buried deep in tissue—all of which make them difficult for surgeons to see and avoid nicking with their scalpels. Now researchers have made a nontoxic formulation of a fluorescent agent that specifically targets nerves (ACS Mol. Pharmaceutics 2015, DOI: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00582). With further development, this kind of agent could be used to help surgeons see nerve tissue during operations.

In the U.S., more than 600,000 patients per year suffer nerve damage following surgery. Summer L. Gibbs, a biochemist at Oregon Health Science University, says this is a particular problem in prostate-cancer surgery, where nicking nerves can lead to incontinence and impotence. “A fluorescent contrast agent that targets nerves would improve visibility for surgeons,” she says. Targeting nerves is challenging because the circulatory system’s protective blood-nerve barrier won’t allow most fluorescent molecules to pass into nerve tissue, because they are too large.

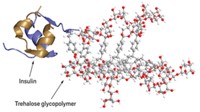

One agent called BMB, small and red, can cross the barrier. But it is hydrophobic so must be formulated in a mixture of toxic solvents, including dimethyl sulfoxide. Gibbs worked with OHSU pharmaceutical chemist Adam W. G. Alani to come up with a safer version. Alani packaged the imaging agent in an off-the-shelf block copolymer based on polyethylene glycol and polylactic acid, which forms micelles around the compound in water and is nontoxic.

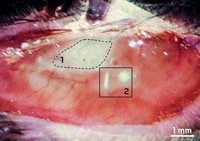

Gibbs didn’t know whether the newly packaged BMB would still be able to target nerves as well as the old, toxic formulation. So she and her colleagues did imaging experiments in living mice and in mouse tissue, comparing the two formulations. “We found something unexpected—the new formulation was much brighter,” says Gibbs. She doesn’t know why it appears to target nerves better, but says the polymer packaging may help the agent circulate longer.

This less toxic formulation is an improvement, but these agents still need development. John V. Frangioni, a professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School and a physician at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center who has started companies to commercialize image-guided surgery systems and agents, says the packaging is good, but the nerve imaging agent inside needs to be a deeper red, in the range of colors that travels farther through tissue before scattering.

Gibbs is working on making a nerve-targeting imaging agent that emits light at a longer wavelength, in the near-infrared part of the spectrum, to minimize scattering. When she’s made that, she’ll combine it with the nontoxic polymer to make the system even better.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter