Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

A Potentially Cheaper Way To Test Food For Pesticides

Food safety: A plant-esterase-based biosensor detects toxic organophosphate pesticides

by Deirdre Lockwood

December 1, 2015

Researchers have built a prototype biosensor that could make it cheaper to detect a common class of toxic pesticides on food and in the environment (J. Ag. Food Chem., DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03971). Organophosphate pesticides represent nearly 40% of pesticides used on crops worldwide, and are highly neurotoxic. Scientists are developing sensitive, portable biosensors that can detect the low limits of these pesticides set by regulatory agencies, or uncover illegal uses of banned compounds.

Organophosphates inhibit acetylcholinesterase—the mechanism of their toxicity in humans—and many current biosensors monitor this reaction. But this enzyme is expensive because it needs to be extracted from animal tissue. So some researchers have considered using a cheaper alternative, plant esterase.

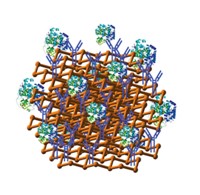

Changjun Hou of Chongqing University and Yu Lei of the University of Connecticut and their colleagues designed a plant-esterase-based biosensor for organophosphates that boosts performance by including nanomaterials used in previous acetylcholinesterase-based biosensors (Anal. Chem. 2012, DOI:10.1021/ac300545p). The new sensor incorporates gold nanoparticles to ease electron transfer, graphene nanosheets to improve conductivity, and chitosan, a hydrophilic polysaccharide derived from shrimp and insect shells, to stabilize the enzyme.

To make the biosensor, the team started with a solution of gold nanoparticles and graphene nanosheets, which they deposited onto the surface of glassy carbon electrodes. Then they extracted and purified plant esterase from wheat flour, and mixed it with chitosan. They applied the solution of plant esterase and chitosan onto the surface of the nanocomponents and let it dry. When the system is placed in a buffer solution containing 1-naphthyl acetate, a carboxylic ester, plant esterase hydrolyzes the ester to produce an electroactive product, 1-naphthol. Organophosphate pesticides inhibit this reaction, so the researchers can determine their concentration in a solution by monitoring the decrease in electrochemical current in the electrodes.

The team used the biosensor to measure concentrations of two organophosphate pesticides, methyl parathion and malathion, in solution at up to 500 ppb. It has detection limits of 50 ppt and 0.5 ppb for these compounds, respectively, comparable to or more sensitive than most previous acetylcholinesterase-based methods and below the maximum limits set by the EPA (2 ppb for methyl parathion). It also accurately quantified spikes of these pesticides on ground up samples of carrots and apples with an average error of 4%.

Though the team’s concept is not unique, it could have potential for food analysis, says Omowunmi A. Sadik, a chemist who develops environmental biosensors at Binghamton University, SUNY. She adds that both the NSF and USDA are stressing the development of less expensive detection methods for food safety. Because these organophosphate compounds are nerve agents, the method could also be used in defense, she says. Still, she says the team must make the prototype portable and robust enough to perform in the “dirty” conditions of the real environment, and that the use of nanomaterials will raise its cost.

Lei says the team hopes to develop a portable device that uses test strips and a simple electrochemical readout, similar to blood glucose meters.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter