Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Drug Development

Three stories of pharmaceutical outsourcing

How three partnerships are riding the drug development road

by Michael McCoy , Ann M. Thayer , Rick Mullin

April 4, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 14

Jump to Topics:

Case study #1: Ramsey Lake and Dalton push cancer drug candidate closer to market

Case study #2: Flexion sets up house with Patheon to make its pain drug.

Case study #3: With support from Almac, Wellstat delivers for a rare disease.

The U.S. Food & Drug Administration approved 45 new drugs in 2015, a 20-year high. Thirty-three of them are small molecules—the products of chemical synthesis.

One of the new drugs is Xuriden, a small molecule from Wellstat Therapeutics that treats an ultrarare disease called hereditary orotic aciduria. By the time Xuriden was approved last September, Wellstat had been working with its active ingredient, uridine triacetate, for close to 15 years.

That’s a long road, but not out of the ordinary. Developing a new drug, from synthesis to approval, takes on average more than 10 years, according to a 2014 report from the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development that looked at 106 compounds from 10 companies.

The Wellstat team is being rewarded for its efforts. Although Xuriden treats only a handful of people worldwide, the company was able to sell a priority review ticket it won from FDA for an undisclosed—but likely multi-million-dollar—sum.

But for every Wellstat that reaches the end of the road, dozens more firms are still riding it. For example, the molecule that Ramsey Lake Pharma is developing, VR23, was discovered in 2008 and has yet to enter clinical trials. Another firm, Flexion Therapeutics, is near the end but still motoring on.

Almost from the start, small drug developers such as Wellstat, Ramsey Lake, and Flexion rely on pharmaceutical services firms to get the job done. In the pages that follow, C&EN presents stories of the relationship between these firms and their service industry partners. As the stories make clear, the road to market is long, but help can be found along the way.

Case study #1:

Ramsey Lake and Dalton push cancer drug candidate closer to market

Alliance of Canadian firms helps small molecule VR23 emerge from Ontario

VR23, a small molecule with cancer-killing potential, started as a gleam in Hoyun Lee’s eye more than a dozen years ago.

Now, thanks to an alliance between Lee’s company, Ramsey Lake Pharma, and the pharmaceutical chemistry firm Dalton Pharma Services, VR23 has taken a step closer to becoming a drug. But it still has a long way to go.

Lee is a Korean immigrant who rose above his beginnings as a corner store operator in Ontario to earn a Ph.D. in molecular virology at the University of Guelph. In the early 2000s, while Lee was working at the Advanced Medical Research Institute of Canada (AMRIC) in Sudbury, Ontario, discussions with an oncologist friend led him to become intrigued by the cancer-fighting potential of chloroquine, a malaria treatment that also has antiviral and antibacterial properties.

Back in his lab, Lee played with the concept for a couple years. “It was slow at first,” he says. Lee found, for example, that chloroquine analogs have anti-breast cancer properties. He also knew that sulfonyl derivatives often possess antitumor activity.

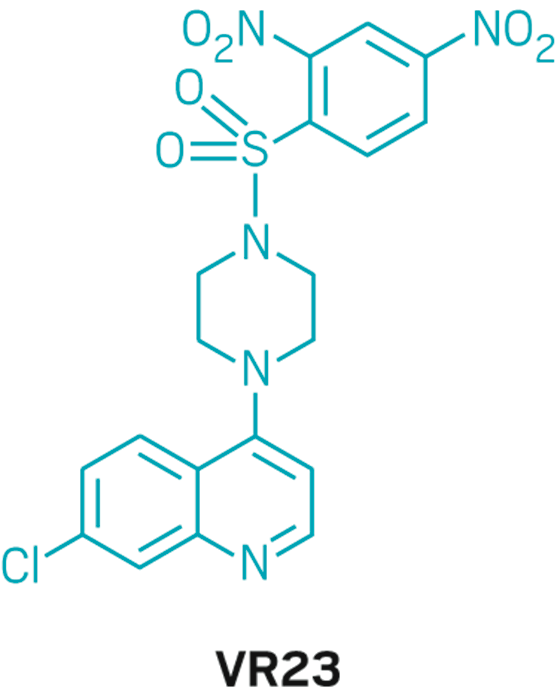

VR23

Discoverer: Hoyun Lee

Year discovered: 2008

Developer: Ramsey Lake Pharma

Mechanism of action: Causes cancer cell apoptosis by inhibiting proteasome activity

Disease indications: Various cancers

Planned start of clinical trials: 2018

In 2006, he hired a postdoc, the medicinal chemist Viswas Raja Solomon, and asked him to start synthesizing chemical libraries, about 50 compounds each, that incorporate a 4-piperazinylquinoline scaffold and a sulfonyl pharmacophore. His thinking was that hybridizing two compounds with anticancer activity might yield a potent cancer-killing molecule with minimal side effects.

Solomon came up with about 300 compounds, which Lee and his team screened against cancer and noncancer cells. Working with other Canadian scientists, they also screened a library of more than 30,000 molecules against the cells. Among all the compounds, the best hit was one that Solomon synthesized, VR23.

The AMRIC researchers followed up with multiple studies in cancer cell lines and mice. They found that, compared with a control, VR23 reduced tumor size—both on its own and in combination with approved cancer drugs such as Taxol and Velcade.

Lee applied for his first patents on a family of compounds that includes VR23 in April 2013. Ramsey Lake, which is a spin-off from AMRIC, licensed a patent portfolio from the institute the following year.

Lee and his team published their results in October 2015 in the journal Cancer Research. They concluded that VR23 causes cancer cell apoptosis, or programmed cell death, by inhibiting proteasome activity. However, unlike other proteasome inhibitors, including Velcade, VR23 has little effect on noncancerous cells.

The Lee team conducted its initial studies with the VR23 that Solomon synthesized. But to carry out a systematic toxicology study that would pass regulatory muster, the scientists needed higher-purity product made in a facility that follows Good Laboratory Practices.

Lee was familiar with Dalton, which is based in Toronto, from previous purchases of research chemicals. He also knew that Dalton could do synthesis under the Good Laboratory and Manufacturing Practices conditions that would be required if VR23 were to enter human clinical trials. So he sent off a request for proposal.

At Dalton, Lee was not a regular customer, but his inquiry was also not a complete surprise. As is often the case in Canada’s intimate pharmaceutical sector, the two companies already had ties.

Peter Pekos, Dalton’s chief executive officer, explains that he knows Ramsey Lake’s CEO, Sean Thompson, from Thompson’s previous job as a business development executive at YM BioSciences, a Canadian cancer drug firm that did business with Dalton. YM acquired Delex Therapeutics, another Dalton customer, in 2005. YM itself was acquired by Gilead Sciences in 2012 for more than $500 million.

Indeed, Pekos is familiar with many of the players in Canada’s pharma sector, having launched Dalton 30 years ago with Douglas Butler, his then-professor at Toronto’s York University. The two-man company started out in the university’s business incubator as a contract chemistry provider.

Although Pekos knows the Canadian industry, he hastens to add that his client list is international; only about 40% are based locally. Some of the local ones, he notes, came to him only after seeing Dalton succeed elsewhere. “When we started, Canadians didn’t think we were any good until the Americans said we were,” he recalls.

Today, Dalton has about 100 employees. At its 3,900-m2 facility, teams are engaged from one end of the drug development process to the other: medicinal chemistry, scale-up and process development, pharmaceutical chemical manufacturing, formulation development, solid dosage forms, creams and lotions, and sterile products.

The focus, Pekos says, is on difficult projects. “A lot of the tricky stuff ends up at our place,” he says.

With business growing in most of these areas, Dalton is expanding. Pekos says the company has spent about $5 million on the Toronto site in the past three years and plans to invest several million dollars more the next 12 to 24 months. Among other things, he wants to be able to accommodate three customer products that are on track to win regulatory approval in 2017 or 2018.

Ramsey Lake is far from that stage. Like many small biotech firms, it is taking things one step at a time, and Lee’s request was a small, one-off project for Dalton.

In taking it on, the Dalton chemists made sure the solvents were appropriate for larger-scale production and did some yield optimization. The contract also called for them to develop analytical testing methods for VR23 and execute a stability study to ensure that the compound has a good shelf life.

Dalton synthesized 100 g of VR23, and now the ball is back in Ramsey Lake’s court. Drawing on funding already at his disposal, Lee is looking for a biomarker that can predict the cancers VR23 will be most effective against. He’s also using a gene knockdown approach to explore low-side-effect combinations of VR23 with other drugs. “Safety is most important for me,” Lee says.

But for larger-scale animal studies and future human clinical trials, Ramsey Lake will need more money. That’s where Thompson, the CEO, comes in. He’s been working the Canadian funding system. For example, Ramsey Lake has won cash from the Northern Ontario Heritage Fund Corp., and it’s looking to participate in the Ontario Bioscience Innovation Organization’s Capital Access Advisory Program.

Real money—of the type that venture capitalists or drug company partners bring—has yet to arrive. But Lee is optimistic. He thinks Ramsey Lake will be ready to start clinical trials within two years.

↑ Top

Case study #2:

Flexion sets up house with Patheon to make its pain drug.

Novel manufacturing relationship yields the microsphere-encapsulated joint-pain reliever Zilretta

It’s a big step in any relationship to live under one roof. But Flexion Therapeutics decided that it had found the right home with Patheon after evaluating a few dozen contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) experienced in handling complex dosage forms.

Flexion and Patheon “fairly quickly aligned,” says Daniel Leblanc, Flexion’s vice president for pharmaceutical development and manufacturing. Patheon not only understood what Flexion wanted to do but was also willing to work on an aggressive timeline. In addition, he says, “the model that they were proposing versus the other CMOs just made the most sense.”

Patheon proposed that Flexion set up a dedicated suite at Patheon’s sterile manufacturing site in Swindon, England. This “condominium” model is one of six flexible approaches to drug manufacturing that the firm has begun offering to customers.

A purpose-built facility helps clients “who have a particular or unique need that doesn’t fit very nicely into standard equipment that the CMO industry has in place,” explains Joe Principe, Patheon’s vice president for strategic partnerships. In this case, the firm met Flexion’s need to use an unconventional drug-polymer matrix technology that it had developed.

The companies announced their relationship in August 2015. After working with Patheon on design, Flexion purchased the required spray-drying and other equipment and brought in its proprietary manufacturing technology. Patheon has been installing the equipment and validating the process. The plant will both make bulk material and fill and finish the final product.

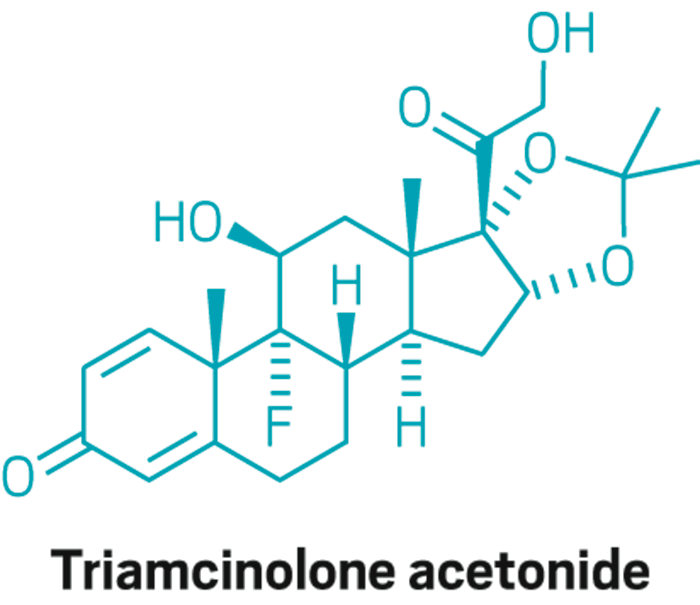

Zilretta

Active ingredient: Triamcinolone acetonidee

Method of action: Analgesic

Delivery form: Injectable corticosteroid encapsulated in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres for sustained release

Disease indication: Intra-articular (in the joint) treatment for moderate to severe osteoarthritis pain in the knee

Status: Fast-track designation awarded in September 2015; Phase III trials results reported in February 2016; Filing for approval anticipated in second half of 2016

All of this is designed for Zilretta, a drug that Flexion anticipates submitting to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration for approval in the second half of this year. Zilretta is a sustained-release version of the generic corticosteroid triamcinolone acetonide. Intended to treat joint pain related to osteoarthritis, the injectable drug improves upon existing oral or injected therapies by providing localized relief for months instead of weeks.

Zilretta is a patented formulation of the steroid uniformly dispersed in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres. As the PLGA polymer is absorbed in the body, the drug gets slowly released.

Flexion licensed the microsphere technology in July 2014 from the Texas-based nonprofit Southwest Research Institute. The process employs a controlled, continuous atomizing technology that Flexion has tweaked to create the proper particle size, drug-loading, and release profile.

In addition to Southwest Research, Flexion worked with Evonik Industries, a CMO that specializes in medical device polymers and controlled-release methods, to scale up the process and produce material for clinical trials.

As an entirely virtual company, nine-year-old Flexion is accustomed to outsourcing all of its development activities. The Burlington, Mass.-based company isn’t naive about what goes on in drug development, however, having been founded, and now run, by former big pharma company managers and scientists.

Leblanc, who worked in drug development at Merck Serono and the drug delivery specialist Alkermes, has learned to choose CMOs on the basis of their strengths. Thus, upon moving in with Patheon, Flexion decided to pare down to a single partner to make the microsphere-based drug. Patheon will also aseptically fill vials with the resulting dry powder and complete packaging of the finished drug product. Evonik continues to provide the PLGA polymer. Italy’s Farmabios supplies the steroid active ingredient.

But it’s not just coordinating the separate activities that makes the condo model work, suggests Martyn Botterill, general manager of Patheon’s Swindon site. Whereas Patheon offers experience in building and operating facilities, its client brings unique technical knowledge through its work on a bespoke process.

“Although we would hope to bring a level of expertise to a project from similar things we have worked on in the past, it is the sharing of knowledge and coworking through the project which makes it so powerful and executable,” he says.

And Flexion can feel at home in a custom-built facility while it also benefits from a leading CMO’s amenities. Patheon staff trained specifically for the project carry out supporting functions such as quality control and analysis, Botterill says. The client “only needs to build that which is very specific to their own process,” he adds.

Advertisement

This setup gives Flexion “the best of both worlds,” Leblanc says. “It’s like building our own facility without having to put the infrastructure in place around quality systems and utilities, because those are already there.”

Another advantage, he points out, is the ability to quickly call upon Patheon experts across all of the company’s sites. “Rest assured that if we say we need help, they have got someone on the phone in five minutes,” Leblanc says. On other occasions, help has even been flown in.

Such service comes at a price, however. Flexion already took out a $30 million loan, mainly to pay for manufacturing equipment. In its 2015 annual report, the company said it anticipates spending a total of $141 million for contract fees and for equipment reimbursement and raw material costs over 10 years. At least $79 million of the total is committed to Patheon for operating the production suite.

But Flexion is looking at a large market opportunity, initially in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. In the U.S., more than 4 million people annually get immediate-release steroid or hyaluronic acid injections in the knee. Steroid injections also are used to treat osteoarthritis pain in the hip, shoulder, foot, and ankle.

As Flexion gets ready to launch its product, the dedicated facility is intended to give it control over production and the flexibility to manufacture on demand, Leblanc explains. Although the company won’t actually be involved in making drug batches, it will have a person on-site to participate, help troubleshoot, and “learn as we go along together, which we wouldn’t get in another CMO model,” he adds.

“It is not just to have someone there 24/7 babysitting the process and monitoring the work—because we trust the relationship and that things will get done—but to actually have someone to partner with Patheon,” Leblanc says.

Flexion expects to continue the relationship and expand further at the Patheon site, he says. Already factored into the model is space for additional capacity.

At the moment, the companies are performing final equipment qualification to start making regulatory-compliant materials early next quarter. “We are just at the completion phase of this first part of the project,” Leblanc says. “The sheer number of different resources available has really helped us to keep to the aggressive schedule that we had in the first place and get to the point where we are today.”

↑ Top

Case study #3:

With support from Almac, Wellstat delivers for a rare disease.

Proximity of API and finished drug development helps uridine triacetate to market for two indications

By Rick Mullin

“The initial contact was a cold call by Almac in 2010 or 2011,” recalls Mike Bamat, senior vice president of R&D at Wellstat Therapeutics, a small drug company in Gaithersburg, Md. “There were probably a couple of calls. It was one of those things where timing is everything.”

Almac, a Craigavon, Northern Ireland-based pharmaceutical services company, was looking to get in on Wellstat’s development of uridine triacetate, a synthetic pyrimidine analog, as an antidote for fluorouracil and capecitabine toxicity and overdose in cancer patients receiving those chemotherapies. And the calls, which Almac records indicate followed some communication between the companies, happened to come just when Wellstat was looking to change service partners as it moved toward commercial development of the drug.

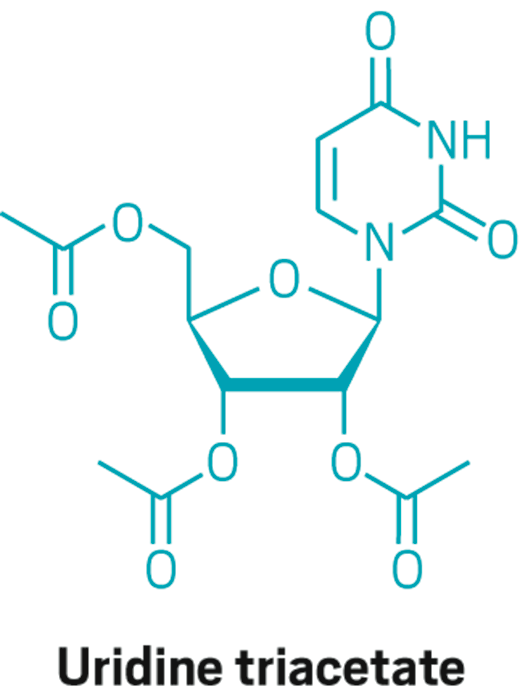

Uridine triacetate

Discovery: Wellstat Therapeutic’s research on the therapeutic potential of exogenous uridine leads to a determination that uridine triacetate is a safe means of delivering the agent

Applications: Treatment of hereditary orotic aciduria (HOA), an extremely rare disease in which the body does not produce uridine, causing overproduction of orotic acid; emergency treatment of toxic reaction to or overdose of the cancer treatments fluorouracil and capecitabine

Methods of action: Treating HOA, uridine triacetate restores intracellular nucleotide concentrations, normalizing orotic acid production; as a chemotherapy antidote, it increases intracellular levels of uridine to dilute fluorouracil and capecitabine

Years in development: Since 2008 for chemotherapy antidote, and 2013 for HOA

Approved: Xuriden for HOA, Sept. 4, 2015; Vistogard for chemotherapy antidote, Dec. 11, 2015

The job went to Almac, as did work that sprang up as the result of another phone call to Wellstat—this one from the U.S. Food & Drug Administration.

As Bamat explains, uridine triacetate caught FDA’s attention regarding another potential indication—an extremely rare and life-threatening disease called hereditary orotic aciduria, or HOA. A consequence of the body’s inability to produce uridine, a necessary component of ribonucleic acid, HOA can manifest in a range of symptoms including blood abnormalities, developmental delays, and urinary tract obstruction caused by overproduction of orotic acid. There have been 20 reported cases of HOA since the 1950s. Only four cases are currently known in the U.S., Bamat says, and likely fewer than 20 in the world.

Wellstat landed approvals for Xuriden, the HOA treatment, in September of last year and Vistogard, the chemotherapy antidote, in December.

The story of Xuriden centers on a raft of FDA incentives for super-rare diseases that enabled Wellstat to move forward on an expedited application for a drug that will never be made in any great volume. But bringing Xuriden and Vistogard to market may also be viewed as the story of a drug discovery firm becoming a commercial enterprise thanks to its partnership with a service provider.

As Wellstat began late-stage development of the chemotherapy antidote, its research partner at the time, QS Pharma, was acquired by the service firm WIL Research. The look and feel of the partnership changed, according to Bamat.

“We kind of lost the small, easy-to-work-with relationship we had with them,” he says. Wellstat also needed support on development and manufacturing of a finished drug product composed of granules delivered in packets or sachets. The drug is administered orally, usually sprinkled on food such as applesauce or yogurt.

Almac was deemed a good fit because of its experience with developing drugs in granule form for “sachet presentation,” a packaging method more common in Europe than in the U.S. The Northern Ireland firm’s ability to develop and manufacture the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and the drug product in one location—at its headquarters—would also prove to be a significant advantage.

The distance between Gaithersburg and Craigavon, however, was a concern, according to Bamat. “We debated it. Especially those of us who knew we would be going there,” he says. “We couldn’t just jump in a car and go. But we looked at a variety of things, including cost and value, and it was all very positive at Almac.”

According to David Downey, vice president of commercial operations at Almac, bringing Wellstat’s work on uridine triacetate to commercial production posed several challenges, the first being to secure supply of uridine starting material, which is extracted from sugar beets by Euticals, an Italian firm. Next was developing a method to control particle size in both the API and the finished product. Almac also had to validate process equipment as it scaled up production.

“Uridine triacetate is Wellstat’s first commercial product,” Downey says. “So we were provided with a process more fit for development than for commercial production.”

The basic formulation of a granule drug product is simple, according to Downey: The API and excipient are mixed in a dry blender. The challenge is developing an analytical regimen to assure the granules are blended uniformly. Meeting the challenge required a high level of coordination between API and drug product process development.

Advertisement

“Wellstat needed a partner that could support them from the API to the drug product,” Downey says. The physical proximity between the Almac facilities in Craigavon conducting API and drug product work was a key advantage, he claims.

“If you listen to our business development people, you’ll hear them use the term, ‘crossing car parks as opposed to crossing oceans,’ ” Downey says, explaining that many competitors who offer API and finished drug services run these operations thousands of kilometers apart from each other, sometimes on different continents.

Before it signed on with Almac, Wellstat had been working with uridine triacetate for about 10 years. Its focus on developing the antidote drug started in 2008. Branching into the HOA treatment, however, upped the stakes.

Clinical study development for an HOA therapy was expedited via a full house of regulatory incentives from FDA, according to Bamat. “We had orphan drug designation, rare pediatric designation, breakthrough therapy designation, and priority review,” he says. “So they really went all out in helping us develop this.”

Although Wellstat was interested in developing a life saving drug for children, it was concerned about paying for it, given the tiny market. “At that time, the rare pediatric disease priority review voucher program was just on the radar,” Bamat says. “FDA said, ‘Consider this new program. Maybe it’s a way that at some risk you could recoup some of your costs.’ We looked at it and were willing to take the risk.”

It paid off. Wellstat was able to sell its priority review voucher—which entitles a company that brings a rare pediatric drug to market to receive expedited review of a subsequent drug—to AstraZeneca last year for an undisclosed amount. Other vouchers sold in 2015 brought high sums, including $350 million for one that AbbVie bought from United Therapeutics in August.

Bamat says Wellstat is not likely to change focus after its success with uridine triacetate. It continues to investigate new indications for the compound and will likely work with Almac on anything going into commercial development.

He emphasizes the importance of maintaining an effective working relationship with an outsourcing partner. “My main consideration is that these are people we can really work with on a day-to-day, week-to-week basis,” Bamat says. “Will the communication be good? Will they be honest and transparent with us, and will we be the same for them? That was a key factor, and we felt it was a plus with Almac.”

↑ Top

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter