Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

A biotech hub grows in Doylestown

Pennsylvania center thrives on local talent but struggles to accommodate demand

by Rick Mullin

August 1, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 31

Merck & Co.’s announcement last month that it plans to cut discovery research staff at three sites in New Jersey and Pennsylvania read like a “dog bites man” story. Laying off scientists is what big drug companies do nowadays in what was once the industry’s R&D breadbasket. It wasn’t Merck’s first reduction in the region. Others, notably Roche, which closed its Nutley, N.J., research center in 2012, also have let a lot of scientists go.

On the other hand, companies are hiring, especially biotech firms in research hubs such as Boston and San Diego. But not all pharmaceutical researchers thrust onto the job market over the past 10 years have had to travel so far to find work, thanks to a thriving research center in Doylestown, Pa., less than an hour’s drive from most of the big pharma research labs in New Jersey and around Philadelphia.

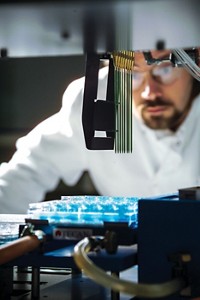

The Pennsylvania Biotechnology Center of Bucks County (BCBC), which opened its doors in 2006, employs some 325 people, including more than 200 scientists. Many of them are entrepreneurs with start-up companies availing themselves of research labs at the 10,000-m2, three-building facility.

The center was founded by the Hepatitis B Foundation in partnership with Delaware Valley University (DVU). It houses the Baruch S. Blumberg Institute, a hepatitis B research organization, and has been a launching pad for successful hepatitis start-ups such as Arbutus Biopharma and Novira Therapeutics, as well as for companies such as Synergy Pharmaceuticals, a publicly traded specialist in gastrointestinal disorders valued at more than $1 billion.

In fact, BCBC, which also houses a huge natural products library acquired from Merck, maintains a constant churn of incoming and outgoing scientists, including former research heads of nearby drug companies as well as faculty chemists from regional institutions such as Princeton University and the University of Pennsylvania.

Although the center maintains a relatively low profile outside the region, BCBC’s tenants like to refer to it as the “Doylestown Corridor”—a one-institution research hub that can be spoken of in the same breath as the major centers. BCBC’s president, Timothy Block, envisions the center growing to be recognized as in a league with Kendall Square in Cambridge, Mass.

Growth, however, has become a serious challenge. A long-strained relationship between the Hepatitis B Foundation and DVU came to a head in 2014 in a standoff that has jeopardized a $4.7 million federal grant to fund a much-needed expansion. BCBC’s board, equally split between the two institutions, has been unable to agree on financing a loan for the matching funds required to receive the federal funding. DVU also opposes filing an application with the state for matching funds.

A lawyer for the Hepatitis B Foundation tells C&EN that the board has been dysfunctional for more than a year. DVU claims that BCBC, which had rental revenue of about $2.2 million last year, would not be able to cover a loan for the matching funds. And BCBC contends that the university, which at one time hosted the center’s research on campus, is looking to be bought out or to take over the center. The center, which saw its grant opportunity expire in March, may soon come under the jurisdiction of a court-appointed custodian.

Block is taking the setback in stride. If the center can reach an agreement with DVU, he notes, the federal grant may still be accessible. Meanwhile, he says his focus remains on fostering an environment for drug discovery and company creation, especially in his primary area of interest, hepatitis B.

Given how Block and his wife, Joan, executive director of the Hepatitis B Foundation, have succeeded in creating a thriving research facility out of a patient advocacy group, it is hard to dismiss the notion that the center could enlarge significantly toward Block’s goal of establishing a world-class research hub.

“Our plan was to build a place where scientists will come and work on a cure for hepatitis B,” says Block, a microbiologist and biochemist, who declines to discuss the “personal situation” that motivates him and his wife. “I was working at the Jefferson Center for Biomedical Research at the time. And this was my goal. My moon shot.”

Started in 1991 by the Blocks and their friends Paul and Janine Witte, the foundation lacked facilities to support research, and for several years it focused on advocacy. “We spent most of our time going around and telling people to get vaccinated,” he recalls.

On a trip to the University of Oxford, Block made two key contacts—Baruch Samuel Blumberg, a geneticist and winner of the 1976 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on hepatitis B, and Raymond Dwek, a biochemist also working on the disease. Block maintained a relationship with the scientists, bringing Blumberg in as a partner in the foundation and working with Dwek on research that led to the founding of Synergy, one of BCBC’s first success stories.

The foundation and DVU received a $7.9 million state grant for the purpose of building research facilities in 2003. Block says he began looking in Bucks County for a location at which to build the center when Pennsylvania Congressman Jim Greenwood, now the president of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, suggested a printing warehouse and factory that had gone out of business.

“A handful of us moved in, and we began spinning out companies,” Block recalls. “Then companies started moving in.”

One was OnCore Biopharma— a hepatitis B firm launched by a group of scientists from Pharmasset, the Princeton, N.J.-based antiviral drug firm acquired by Gilead Sciences. Another was Novira, a hepatitis B company launched by Osvaldo Flores, former head of virology discovery at Merck, and George Hartman, former director of medicinal chemistry at Merck.

OnCore, which merged with Tekmira Pharmaceuticals to form Vancouver, British Columbia-based Arbutus last year, maintains 25 people at the Doylestown facility. Novira, acquired late last year by Janssen, will be leaving the center to work at Janssen’s nearby facility in Spring House, Pa.

Pharmasset’s research group, led by Michael Sofia, developed sofosbuvir, a hepatitis C drug now marketed by Gilead as Sovaldi. Sofia says OnCore was formed to pursue a similar treatment for hepatitis B, and the Doylestown center was an ideal place to get started.

“This facility is one of the only ones of its type that could provide a lab and office space at a reasonable price with an infrastructure to support it,” says Sofia, now chief scientfic officer at Arbutus. Its location, a short drive from Princeton, and its background in hepatitis B were obvious advantages, he says.

OnCore licensed three programs from the Hepatitis B Foundation and has grown to occupy five labs. Since the merger, Arbutus has maintained virology, immunology, and discovery groups at Doylestown and continues to hire chemists, Sofia says. And given the downsizing at big pharma, there are plenty available.

The problem is where to put new employees. “We’re pretty cramped,” Sofia acknowledges. “The good side and the bad side about this facility is that it has become a magnet for people starting up companies.”

To accommodate the growing company, BCBC erected a loft-level office space in one corridor of the facility. “The biotech center has been extremely accommodating in working with tenants to find space,” Sofia says, “but the popularity of the facility has gotten to the point where there is no space.”

One of the first things Novira did when it came to BCBC in 2012 was erect its own lab and office space with the $3 million the company had garnered in venture capital investment. But the space Novira is occupying—three labs and support offices for 17 employees—will soon become available when the company relocates.

Flores, who is now head of discovery for hepatitis B at Janssen, says that as a largely virtual company, Novira could have set up anywhere. But, like Sofia, he saw obvious advantages to coming to BCBC—which he had not heard of, despite working 20 minutes away at Merck’s West Point, Pa., facility—given its community of hepatitis B research.

Flores, who started his career at San Francisco-based start-up Tularik before it was acquired by Amgen, was enthusiastic about leaving Merck in 2009. “I had a desire for a fast-paced environment where I am not held down by the bureaucracy and complexity of a large company,” he says. “Don’t get me wrong—to be effective in drug discovery, having experience in big pharma is essential. But after learning the rigor and discipline there, it was time for me to go back.”

In fact, Novira has moved at lightning speed, taking its lead drug candidate from discovery through Phase I clinical trials in less than three years and producing results that got Janssen’s attention. Flores says the company did this using a minimal number of on-site researchers and relying heavily on contract research organizations in China and Germany. It has also been able to attract top talent. “Almost everyone I hired at Novira is from Merck or Roche.”

But a talented workforce is only one component in establishing a successful biotech company, Flores adds. Also necessary are local sources of venture capital and a pool of experienced executives. Novira received initial seed funding from BioAdvance, a Philadelphia-based venture firm. And there are experienced managers in the region. But there is nowhere near the concentration of venture funding sources and scientists with start-up experience that can be found around places like Boston.

William A. Kinney, director of the Natural Products Discovery Institute at the center, can attest that entrepreneurial researchers entering the center face a steep learning curve. Kinney, a medicinal chemist who has worked at Wyeth and Johnson & Johnson, also has a medicinal chemistry consulting company called IteraMed and a natural-products-based drug discovery firm called Revive Genomics, both of which he started at, and operates from, the center.

In addition, Kinney works as the chief scientific officer for Kannalife Sciences, another start-up at BCBC. He continues to manage the natural products institute—a collection of 100,000 extracts and 50,000 microorganisms that Kinney claims represents 60% of the world’s higher plant genera—but says the institute’s staff of three scientists have become increasingly self-directed at providing drug discovery services based on the collection. This, he says, gives him more time to pursue the other ventures.

“The business development stuff was totally new to me,” he says. “But the beauty of this place is that it teaches you to be an entrepreneur. Most of us were brought up in the pharma world where you have job security. You just had to come up with ideas from year to year. Here, you have to find a way to fund your enterprise.”

And funding fluctuates for many of the companies at the center, Kinney says, creating a kind of fluidity that actually helps cross-pollinate research. “One minute I may be working for the Blumberg Institute, then one of my clients takes off and I spend time working with them. There is a lot of that flow between companies working at the center.”

Although Block strives to keep companies on-site as they grow and laments BCBC’s inability to accommodate significant expansion at the moment, he also sees the fluidity and turnover as healthy.

Moreover, he remains optimistic that the Hepatitis B Foundation and DVU will reach an agreement to proceed: At stake is a 3,500-m2 expansion.

“It would give us modern facilities,” Block says. “If we got the new building, we’d have between 400 and 500 people working here. Arbutus would be able to add another 100. We would be well on our way to a thousand. Our plan is to build this into a biotech corridor like Kendall Square.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter