Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Vinpocetine: drug or dietary supplement?

FDA signals intent to regulate semisynthetic dietary ingredient as a drug

by Britt E. Erickson

October 31, 2016

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 94, Issue 43

It enhances athletic performance. It boosts memory. It helps weight loss. These are claims from companies marketing dietary supplements containing vinpocetine, a semisynthetic chemical derived from the lesser periwinkle plant.

The substance has been sold to U.S. consumers for nearly 20 years as a dietary supplement. But in Germany, Russia, and China, it is considered a pharmaceutical available by prescription to treat stroke and cognitive impairment.

To the surprise of the supplements industry, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration is now proposing to change the status of vinpocetine to a drug. That means manufacturers will have to demonstrate safety and efficacy before they can market products that contain the chemical. Plus, they will have to ensure that accurate dosages are included on product labels.

Critics of the supplements industry argue that such a change is needed because companies are bypassing FDA safety and efficacy reviews and selling pharmaceutical ingredients directly to U.S. consumers as dietary supplements.

The natural products industry is shocked by FDA’s tentative decision. Companies claim that removal of vinpocetine from dietary supplements will be a huge cost for manufacturers resulting in little public health benefit. It will also set a precedent for FDA to scrutinize other new dietary ingredients found in supplements, they say.

Popping pills

Dietary supplement use is strong in the U.S.

Key figures:

▸ 52% of U.S. adults report using dietary supplements within the past 30 daysa

▸ 31% of U.S. adults report using multivitamin/mineral supplements within the past 30 daysa

▸ 55,600 dietary supplements are estimated to be available in the U.S.

▸ 5,560 new dietary supplement products are estimated to hit the U.S. market each year

Legal definitions:

▸ A “dietary supplement” is “a product intended for ingestion that contains a ‘dietary ingredient’ intended to add further nutritional value to (supplement) the diet.”

▸ A “dietary ingredient” may be one, or any combination, of

▸ a vitamin;

▸ a mineral;

▸ an herb or other botanical product;

▸ an amino acid;

▸ a substance to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake; or

▸ a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, or extract.

a Data are from 2011–12.

Source: JAMA 2016, DOI: 10.1001/jama. 2016.14252

The debate began in September when the FDA tentatively concluded that vinpocetine is not a dietary ingredient. If the agency finalizes that decision, vinpocetine will no longer be allowed in supplements and FDA will regulate the chemical as a drug.

FDA claims that vinpocetine does not fit any of its categories for dietary ingredients. The compound is not a vitamin, mineral, amino acid, or botanical substance.

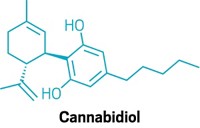

Nor is it a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, or extract, the agency says. The chemical has never been identified in a plant. It is chemically synthesized from vincamine, an alkaloid extracted from the leaves of the lesser periwinkle (Vinca minor).

FDA also points out that several clinical trials were conducted on vinpocetine in the 1980s. These studies are important because of the legal definition of a dietary supplement. That definition excludes substances that have been authorized for clinical investigations as a new drug, unless the substance was marketed as a dietary supplement before the clinical trial was authorized. Vinpocetine was first sold in the U.S. in 1997, well after the clinical trials.

Triggering FDA’s action on vinpocetine was a study published in 2015 by Pieter Cohen, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and colleagues at the University of Mississippi (Drug Test. Anal. 2015, DOI: 10.1002/dta.1853). The researchers analyzed 23 vinpocetine supplements purchased online from two large retail chains, General Nutrition Center (GNC) and the Vitamin Shoppe. Most of the supplements had inaccurate information about the presence or quantity of vinpocetine, the team reported.

Six of the samples contained no vinpocetine at all, and 17 had levels ranging from 0.3 to 32 mg, the researchers noted. Vinpocetine is prescribed as a pharmaceutical in some countries at dosages from 5 to 40 mg.

“We found that only 6 of the 23 supplement labels (26%) provided consumers with accurate dosages of vinpocetine,” Cohen writes in a letter to the editor, published last year in Mayo Clinic Proceedings (DOI: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.07.008).

Studies investigating the neuroprotective benefits of vinpocetine have shown mixed results, Cohen points out. Some studies show benefits; some do not. Others suggest the substance can lead to negative health effects, including flushing, headaches, and low blood pressure.

“FDA has permitted an unapproved new drug with unproven efficacy and known adverse effects to be sold directly to consumers,” Cohen says. “By permitting the sale of a drug as a dietary supplement, the FDA has created a dangerous precedent by which new drugs can bypass the rigorous drug approval process and be sold directly to consumers without FDA approval.”

In response to the study by Cohen and colleagues, Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.), the top Democrat on the Senate Special Committee on Aging, started urging FDA to suspend sales of vinpocetine supplements. In 2015, she also asked 10 retailers to voluntarily stop selling vinpocetine products.

“The way we regulate these supplements isn’t working—and it’s putting the lives and well-being of consumers at risk,” McCaskill said at that time. “We’ve seen products with false labels, tainted ingredients, wildly illegal claims, and, now, products containing synthesized ingredients that are classified as prescription drugs in other countries.”

The lawmaker’s request did little, however, to sway the supplements industry. Now, one year later, hundreds of dietary supplement products that claim to contain vinpocetine are still widely available in the U.S.

Makers of vinpocetine are stressing the immensity of the market as FDA considers regulatory action. The Natural Products Association (NPA), an industry group, is urging FDA to conduct an economic impact analysis before making a final decision.

Dietary supplement companies have been lawfully marketing vinpocetine since the 1990s, notes Daniel Fabricant, chief executive officer of NPA. “It would appear that removal of this ingredient would bear little incremental public health effect,” he says, “but a significant incremental cost associated with the change in regulatory status.”

FDA has cleared vinpocetine five times as a new dietary ingredient, with the first instance occurring in 1997. In each case, the agency raised no concerns over the ingredient or the safety data provided by manufacturers. Changing the regulatory status of vinpocetine nearly 20 years later “sets a very bad precedent,” Fabricant says. FDA’s proposal for vinpocetine has “major implications” for dietary ingredients that are being sold in supplements, he says.

Over the past three years, FDA has ramped up its efforts to ensure the safety of dietary supplements. The agency’s proposed decision on vinpocetine comes on the heels of draft guidance designed in part to boost premarket safety notifications for new dietary ingredients in supplements. The agency released that draft guidance in August.

FDA says it will “remove from the market products that contain potentially harmful pharmaceutical agents, are otherwise dangerous to consumers, or are falsely labeled as dietary supplements.” The agency also says that it will “enforce the dietary supplement Good Manufacturing Practices regulation and take action against claims that present a risk of harm to consumers (such as egregious claims of benefit in treating serious diseases) or economic fraud.”

More than 55,600 dietary supplements are available in the U.S., and 5,560 new dietary supplement products enter the market each year, according to FDA estimates. Yet the agency has received less than 1,000 notifications for new dietary ingredients since 1994.

“Notification of new dietary ingredients is the only premarket opportunity the agency has to identify unsafe supplements before they are available to consumers,” says Steven Tave, acting director of FDA’s Office of Dietary Supplement Programs. “The revised draft guidance is intended to improve the quality of industry’s new dietary ingredient reporting so FDA can more effectively monitor the safety of dietary supplements.”

Under the 1994 federal Dietary Supplement Health & Education Act, companies must notify FDA at least 75 days before marketing a supplement that contains a new dietary ingredient. A new dietary ingredient is defined by law as one that was not marketed in the U.S. before Oct. 15, 1994, unless the ingredient is used in the food supply without being chemically altered.

The supplements industry is worried that regulators will soon begin scrutinizing all new dietary ingrdients.

If FDA revokes the status of vinpocetine as a dietary ingredient, it opens the door for the agency to question the status of other dietary ingredients. Dietary supplement manufacturers hope FDA’s action on vinpocetine is not the start of a new trend.

“FDA appears to be attempting to shift the burden of demonstrating reasonable expectation of safety for vinpocetine on the industry by using the hook that it can’t qualify as a dietary ingredient,” Fabricant says. “Is this what responsible industry can expect in the future with other new dietary ingredients?” he asks.

More than half of U.S. adults take dietary supplements, according to a study published earlier this month in the Journal of the American Medical Association (DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.14403). “Consumers are demanding products that complement their individual health needs, and that’s why a majority of Americans continue to trust and use dietary supplements safely on a daily basis,” Fabricant says. “Addressing consumer confidence and safety is an area that our industry cannot afford to compromise.”

But critics of the dietary supplements industry say FDA needs to do more to ensure the safety and efficacy of such products. “For the majority of adults, supplements likely provide little, if any, benefit,” Cohen writes in an editorial accompanying the study in JAMA (2016, DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.14252).

Cohen believes FDA could start improving the situation by finalizing its proposed conclusion about vinpocetine. “This will send a very important signal throughout the industry and to consumers,” he writes in comments submitted to FDA.

Sales of dietary supplements should “not provide a back door to introducing new drugs directly to consumers without FDA approval,” Cohen adds.

FDA is accepting comments from the public about its decision to change the regulatory status of vinpocetine until Nov. 7.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter