Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Newscripts

Roadkill to drug discovery

by Ryan Cross

April 17, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 16

When driving down Highway 9 in Norman, Okla., Robert H. Cichewicz pays special attention to grisly sights of matted fur and dried blood that most people try to avoid seeing—but don’t manage to avoid hitting.

Cichewicz is a natural products chemist at the University of Oklahoma who scours the molecular makeups of fungi and bacteria to find potential drug candidates. And he has chosen critters with the misfortune to wind up as roadkill as his next unexplored microbial treasure trove. The animals are already dead; “we just take advantage of the fact that they are lying there,” Cichewicz tells Newscripts.

About a decade ago, Cichewicz became interested in isolating natural products from the microbiome—the ecosystem of microorganisms that live in and on the body. Anticipating a congested research space for human microbiota, he turned to nonhuman mammalian microbiomes. Studying wild animals means trapping and tranquilizing, though, plus the oversight of animal ethics committees. “And paperwork is no fun. I have enough problems to deal with,” Cichewicz says.

Then one day, a simple solution dawned on him. “There are just all these animals sitting right there on the way to work on the road,” he says. “They are perfect subjects for this scientific inquiry.”

In a study published last month, Cichewicz, Bradley S. Stevenson, and others from the University of Oklahoma described their “opportunistic” approach to mammalian natural products discovery (J. Nat. Prod. 2017, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00772).

Stevenson, a microbiologist, explains that the goal is not to examine the postmortem microbiome but rather to find recently deceased critters whose microbiomes resemble those of a live animal. “Chances are they were relatively healthy, just at the wrong place at the wrong time,” he says.

Cichewicz and Stevenson cruise down the highway at night and make note of any roadkill they see. About eight hours later, they drive along the same road with students or postdocs in tow and stop to look at any new roadkill that appeared since the night before. “That way we get as fresh carcasses as possible,” Stevenson explains.

Opossums are the most common victims, but the team has also sampled armadillos, deer, raccoons, skunks, and squirrels. Rather than take the deceased animals back to the lab, they swab unsquished orifices and organs—eyes, ears, mouths, noses, rectums, and gastrointestinal tracts—for microbial samples roadside.

Cichewicz and Stevenson have developed an eye for roadkill that’s worth taking their time and a bit of a risk for. “You are on the highway,” Stevenson says. “There’s a reason there are carcasses all over the place.”

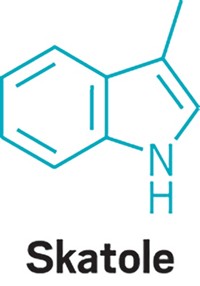

Although some people boil down their research to “sticking a Q-tip in an opossum ear,” Cichewicz says it’s not that easy. Back in the lab, isolated microbial samples on petri plates are subjected to laser ablation electrospray ionization mass spectrometry to identify potentially interesting compounds in microbe colonies. So far, they’ve discovered several new molecules called serrawettins, from the bacterial genus Serratia, which proved to effectively inhibit biofilm formation of a common yeast, Candida albicans, that is pathogenic to humans.

The roadkill researchers hope the workflow laid out in their study will enable their group and others to discover more products in the future. And although Cichewicz is interested mainly in human therapeutics, he also notes that the isolated microbes could prove to be ideal species for investigating as potential probiotics for livestock such as swine or cattle.

Stevenson says the research has made for lively conversations at dinner parties. “People also contact us, instead of animal control, and let us know when they see carcasses on the road,” he says. It’s a nice thought, in an odd way, although by then the roadkill is a bit stale for their research.

Cichewicz’s and Stevenson’s resourcefulness would surely resonate with Jed Clampett of the 1960s TV sitcom “The Beverly Hillbillies.” As Jed says, “That’s the thing about possum innards: They’s just as good the second day!”

“But it’s not a joke,” Cichewicz says. “It’s serious research.”

Contributing editor Ryan Cross wrote this week’s column. Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter