Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Education

Newscripts

Illuminating correspondence from readers

by Stu Borman

May 29, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 22

A glowing discovery lost on management

“Letters, we get letters, we get stacks and stacks of letters.” This member of the Newscripts gang is showing his age because that is a song lyric from the 1950s “Perry Como Show.” Other notable talents include singing the Cream of Wheat advertising jingle and reciting the introduction to the original “Adventures of Superman” TV show with George Reeves.

But back to the letters. Like Perry Como, Newscripts also gets letters, or at least e-mail, and two recent missives were particularly illuminating.

Consultant Edwin A. Chandross of Murray Hill, N.J., wrote to say he enjoyed a March 20 C&EN article on chemiluminescence (page 5), and, by the way, he invented the now-ubiquitous chemiluminescent glow sticks serendipitously in the 1960s.

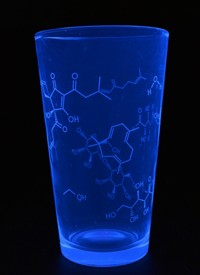

Glow sticks are plastic tubes containing a solution of an ester, such as diphenyl oxalate, and a fluorescent dye. Each tube also contains a breakable inner tube containing hydrogen peroxide. Bending a glow stick breaks the inner tube, allowing hydrogen peroxide and the ester to react. The reaction product is an unstable compound like dioxetanedione, which releases energy that excites the dye, producing fluorescence.

“The beauty of the process is that any fluorescent species can be excited, which is why these devices come in so many colors,” Chandross explains in an essay that appears in the 2011 book “Bell Labs Memoirs: Voices of Innovation.” He discovered the glow stick phenomenon by accident while doing other research at Bell Labs and published a paper on it (Tetahedron Lett. 1963, DOI: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)90712-9). Bell Labs considered patenting the discovery but decided not to do so, not realizing at the time how commercially important glow sticks would turn out to be.

American Cyanamid, supported by the Department of Defense, which wanted ways to locate downed aviators in the sea at night, developed and commercialized glow sticks based on Chandross’s published concept. Glow sticks are “now manufactured by several companies and well known all over the world,” Chandross notes. “The military is still a big customer. And, of course, many kids carry them in their trick-or-treat quest on Halloween,” among many other popular uses.

As a result of Bell Labs’ patent inaction, neither the company nor Chandross ever benefited from the discovery financially. “My family still gives me flak over the refusal of the patent department to file on this,” Chandross writes. “I wish I had been smart enough to realize the applications for this chemistry. Too bad that the management, much more sophisticated than a 29-year-old researcher, did not see them either.”

NMR night-light

In another letter of glowing importance, Paul-James Jones of New Britain, Conn., wrote Newscripts to say that he appreciated the magazine’s article about converting a nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer’s outer vacuum jacket into a combination pizza oven and fire pit (April 24, page 48).

Jones showed similar originality by converting an old broadband NMR probe into a night-light. “By carefully drilling out the center of the probe, inserting a tricolor light-emitting diode where the sample would ordinarily sit, and then wiring the LED to the existing radiofrequency leads, it is possible to create a switchable night-light,” Jones writes.

Applying low direct-current voltages to the radiofrequency channels makes the LED “sample” glow in different colors. “The color palette one can achieve is virtually unlimited, depending on the relative voltages applied to each of the three channels,” Jones notes. “You are only limited by your imagination.”

Stu Borman wrote this week’s column. Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter