Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Cheaper by the barrel

With the help of chemical makers, U.S. energy companies are reducing the cost of extracting oil from the ground

by Alexander H. Tullo

July 3, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 27

Big changes are afoot in the U.S. oil patch. The past 10 years brought horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, which unlocked unprecedented amounts of oil and natural gas from shale formations and restored the competitiveness of the U.S. chemical industry.

Now, oil companies are improving on those methods by slashing the high costs associated with fracking. When oil sold for $100 per barrel, it didn’t much matter how they teased it out of the ground. But when it fell to $30 per barrel, they either had to do it more cheaply or halt drilling. They have reduced costs per barrel by $20 or more, enough to make production economical again, even at low prices.

The downturn also hit the companies that supply oil-field chemicals. Some of their wares fell out of favor; others became in vogue. They also smelled opportunity. A lot of the changes in the oil field stem from economies of scale. This new critical mass is allowing chemical companies to get more creative with their chemistry tool kits.

We normally think of oil and natural gas as raw materials for the chemical industry. But it works both ways. Oil companies can’t extract oil from the earth without chemicals.

Chemical companies supply scores of materials—largely polymers and surfactants—used in the oil field. The industry classifies the chemicals using three categories. One is chemicals used in the well-drilling process, such as lubricants that ease a drill bit’s way or keep it free of corrosion.

Chemicals used to stimulate wells and get them flowing are another class. One example is the gels used to carry proppants. Essential to extracting oil today, proppants are particles of sand meant to “prop” open the cracks that are created in oil-bearing rock by the ultrahigh pressure of the hydraulic fracturing process.

The cost of an oil well

Chemical ingredients influence the cost of drilling fluids, well cement, and completion fluids.

▸ 24% Fracturing pumps and equipment: Equipment used to pressurize fluid in the well to crack the rock formations

▸ 15% Rig and drilling fluids: Process of drilling the well, including fluids used in drilling

▸ 14% Proppant: Material, normally sand, used to “prop” open cracks in the rock formation

▸ 12% Completion fluids: Water and chemical additives, including those used for treatment and disposal

▸ 11% Casing and cement: The pipe and cement that line the well

▸ 23% Other: Various other costs, such as insurance, consulting, and surface equipment

Note: Percentages do not total 100% because of rounding.

Source: IHS Markit

The third class is production chemicals. It includes inhibitors that prevent accumulation of flow-disrupting paraffins and mineral scale. Demulsifiers, which separate oil and water coming out of the well, are critical for readying the oil for refining.

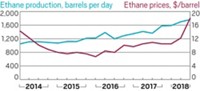

Makers of all these chemicals were hit last year, when after years of boom, lower prices busted the oil industry. From a high of $107 per barrel in June 2014, oil prices plummeted to $26 in February 2016. They slowly inched back and have been hovering at around $50 for the past six months.

U.S. oil and gas drilling activity followed a similar path. The rig count—the number of new wells being drilled—peaked in September 2014 at 1,931, according to the oil services firm Baker Hughes. By May of last year, it bottomed out at 404. It has since climbed to more than 900.

The drilling drop brought hard times to the oil services industry. In 2014, Baker Hughes earned $3.2 billion on $24.6 billion in sales. In 2016, it lost $1.2 billion on $9.8 billion in sales. Its North American sales were particularly hard hit, coming in at one-quarter of what they were two years before.

Among chemical makers, Lubrizol decided to wind down its oil-field chemicals business earlier this year by selling pieces of the unit and shutting other parts down. It had acquired the business for $750 million from Weatherford International in 2014. With the exit, Lubrizol parent Berkshire Hathaway incurred a $365 million loss.

Chemical suppliers that stuck with the business also suffered. Ecolab’s energy unit saw a 20% decline in sales between 2014 and 2016. Solvay’s Novecare business, which houses its oil-field chemical operations, posted an 18% sales decline over the same period. Clariant reported that its sales to the sector slipped by single digits in 2016.

Emmanuel Butstraen, president of Solvay’s Novecare business, says the decline in market demand as oil prices sunk and drilling dried up was significant. “At a certain time, the drop was tremendous, bigger than 50%,” he says, adding that the market has stabilized over the past six months.

Different parts of the oil-field chemicals industry felt the downturn differently. Larry Ryan, president of energy and water solutions for Dow Chemical, says drilling and hydraulic fracturing, which are at the beginning of the oil extraction process, were hit harder and earlier than downstream operations such as oil production and refining. “We saw dips, but generally people were still producing oil and natural gas and were still refining,” he says.

Jeroen Pul, global marketing manager for oil-field applications at AkzoNobel, explains that drilling is a capital-intensive endeavor that oil companies put off during lean times. “They don’t want to open up new wells,” he says. “They want to make the most of the wells they already have in production.”

Overall, according to a 2015 report by the market research firm IHS Markit, worldwide sales of specialty chemicals used in oil fields were $25 billion in 2014. The report’s author, Stefan Schlag, senior director of inorganic chemicals and mining products for IHS Markit, estimates that the market may have declined by as much as 20% over the following two years.

The slump in prices has had a lasting effect on the oil industry. Even before 2014, oil producers were looking for ways to improve efficiency. The hard times intensified their focus. “In a crisis mode, it is cost, cost, cost, cost, cost,” Solvay’s Butstraen says. “Either you make cost reductions and survive, or you are dying.”

The amount by which oil companies have been able to cut costs is stunning. A report IHS Markit prepared for the Department of Energy last year found that from 2012 to 2015, well-drilling and completion costs declined by as much as 30% per barrel of oil. The report expects a further 7 to 22% decrease by 2018. The sharp decline means that cost savings in excess of $20 per barrel aren’t uncommon.

The report credits a number of evolving practices. For example, whereas companies once drilled wells 300 meters deep into a rock formation, they are now going for up to 3 km. The report also singles out multiwell pad drilling, in which up to eight wells, all heading in different directions, are drilled on a site instead of just one or two.

Another change is in the use of proppant. Caldwell Bailey, a senior consultant for IHS Energy, says companies have been using more proppant to make wells more productive. In 2014, each well averaged 1,800 metric tons of proppant. Now 4,000 metric tons is the norm.

Moreover, the chemical nature of the proppant has changed: Companies are using more regular sand and less resin-coated sand (RCS) and ceramics. “Ceramics and RCS are more expensive,” Bailey says. In 2014, 7.5% of the proppant used was ceramic or RCS. That number is now 3.1%.

Oil companies also targeted specialty chemicals for savings, AkzoNobel’s Pul says. “With oil prices of $100 plus, companies were very interested in looking for high-tech solutions,” he says. “Margins were good. All they wanted was the best money can buy. But when the oil price crashed in 2014, the mind-set of our customers changed dramatically and the focus became very much on cost.”

For Chen Pu, Solvay’s executive vice president of oil and gas, a good example of cost-cutting in oil-field chemicals is reducing the amount of guar gum-based gels to carry the proppant. Companies are increasingly using more cost-effective “slick water” technologies that incorporate polyacrylamide friction-reducing agents. Guar imports to the U.S. from India, he notes, have seen a significant drop.

The oil industry is also using chemicals more judiciously, Dow’s Ryan says. “We’re able to optimize formulations a lot better now with folks to help get them to the same production,” he says. For instance, he cites controlling microbes by using the optimal amount of biocide rather than a preset amount, whereby biocide may be wasted.

More meticulous oil-field development and changes such as multiwell drilling are decreasing chemical costs as well, Ryan adds. Now, an oil company might pool the water from 100 wells into a single treatment system. Impurity levels are more consistent that way, and the economies of scale are greater. “They treat it like a manufacturing operation,” he says. “You get a lot of efficiencies with that approach.”

Centralization also provides the critical mass to, for example, remove low-level impurities that smaller operations couldn’t capture. “When they are consistent, we can work with them to provide better chemical solutions,” Ryan says. “That wasn’t the case four or five years ago when the market was just kind of going crazy drilling wells everywhere.”

If oil prices climb back past $80 per barrel, costs will likely creep up, too, most experts say, but not to yesterday’s levels. “You are seeing this step change in the overall cost of a well,” Ryan says. “I would be hard pressed to think you give all of that back.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter