Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

ACS Meeting News

Confronting sexual harassment in chemistry

Awareness is growing among academic departments and scientific societies about the potential damage to individuals and the discipline

by Linda Wang , Andrea Widener

September 18, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 37

“The shame of being involved in a harassment situation is quite overwhelming. You don't want anyone to know because you think they will wonder how a smart woman could ever get into a situation like that.”

“The shame of being involved in a harassment situation is quite overwhelming. You don't want anyone to know because you think they will wonder how a smart woman could ever get into a situation like that.”

It started innocently enough. He was a prominent chemistry professor at a major research university, and she was eager to make a good impression. “I was a pretty insecure grad student in my early years, and the fact that he was paying attention to me and interested in my work and how I was doing in his class was kind of flattering,” says Tara (not her real name).

In brief

Chemistry has the same discouraging sexual harassment problem as the larger science community and the nation, where surveys show at least 25% of women have been harassed at work. Despite that, most women don’t report their experiences, in some cases for fear of damaging their careers. Read on to discover the stories of chemists who experienced sexual harassment and to learn what individual chemists, universities, and associations—including ACS—are doing about the issue.

The professor was not her adviser. Nevertheless, “He invited me to lunch a few times and just sought me out quite a bit. And then he invited me over to his house to watch a movie. He didn’t do anything inappropriate. But after that night, I was like, ‘Something’s weird here; he has a family.’ And his family was away for the weekend.”

Those seemingly innocent actions became increasingly inappropriate. “The culmination was when he wrote me a love note. It was a proposition note, I guess. It basically said he wanted to have an affair with me. I stormed into his office and said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me. This is offensive. I thought you were hanging out with me because I was talented.’ ”

After that incident, Tara went out of her way to avoid the professor. “It was really hard,” she says, in part because his office was along the hallway she traversed between her lab and desk. Yet she didn’t report the situation to anyone. “I felt guilty, like I had somehow done something to have brought this on,” she says.

Tara’s story is a common one in university chemistry departments nationwide, echoing the problems of sexual harassment in the larger science community and the nation. While chemistry hasn’t had a sexual harassment case come to national prominence yet, most female chemists can tell stories of harassment or discrimination of themselves or their colleagues. It may be among the reasons women aren’t reaching parity in chemistry Ph.D. programs and faculty positions.

“It was one of the many factors why I ultimately was unsatisfied and uncomfortable in science,” says Tara, who completed her Ph.D. but decided to leave chemistry and is now working in an unrelated field.

The culture that allows harassment within male-dominated academic chemistry departments has been slow to change. But increased attention to sexual harassment in the larger science community—spurred by public harassment investigations into academic scientists, including former University of Chicago molecular biologist Jason Lieb and former University of California, Berkeley, astronomer Geoff Marcy—is shining a brighter light on the problem.

Many U.S. universities are now paying attention to the discriminatory behavior for the first time, forced in part by new interpretations of Title IX, the 1972 law that prevents discrimination based on sex. Scientific societies are also exploring ways to address sexual harassment, and women are publicly banding together to support each other. The National Academy of Sciences has launched a study of the issue. At the same time, some advocates caution that common practices intended to root out harassers may at best be neutral and at worst could backfire.

As discussion of sexual harassment becomes more prominent in the scientific community, survivors are slowly starting to speak out. C&EN is telling the stories of many female chemists who contacted us about their harassment experiences, but we are protecting their identities because they fear further discrimination if their experiences are revealed. Studies show that just 6% of sexual harassment survivors report it, for reasons that include fear for their safety, fear for their future career, and belief that it’s their fault.

“It’s just astonishing to me how the problem persists,” says Cynthia Lewis, an English professor at Davidson College who is writing a book about sexual harassment by faculty. “We are in a transitional period, when the situation is becoming more and more acknowledged. But there is a long way to go.”

Learning the facts

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission definition of sexual harassment

Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitute sexual harassment when this conduct explicitly or implicitly affects an individual’s employment, unreasonably interferes with an individual’s work performance, or creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment.

Sexual harassment is certainly not unique to academia. Surveys show that 25% of women in the workplace—and 10% of men—experience sexual harassment. But unlike companies, universities are particularly prone to overlook harassment because of their faculty members’ independence, says Billie Dziech, coauthor of the 1984 book “The Lecherous Professor,” one of the first to call attention to sexual harassment by faculty.

Lacking a manager looking over their shoulders, faculty members have almost total freedom. “Then, even if we transgress, there’s so much diffusion of authority. Nobody is willing to take responsibility,” says Dziech, an English professor at the University of Cincinnati.

But universities also have a special responsibility to students, Davidson College’s Lewis says. “Education is built on trust between a faculty member and a student,” she explains. “It strikes me that the very last place where this should happen is in a school, except for maybe the church.”

“I felt guilty, like I had somehow done something to have brought this on.”

—“Tara,” sexual harassment survivor

“I felt guilty, like I had somehow done something to have brought this on.”

—“Tara,” sexual harassment survivor

Lewis started writing her book after decades of seeing overlooked or tacitly condoned faculty-student relationships that later ruined the careers of promising female students. “To me there’s a special heinousness, a moral objectionability about it happening in a place” that is founded on trust between a teacher and a student, she says.

And it’s clear that sexual harassment is common in academia. A 2015 survey by the Association of American Universities of 27 research universities showed that 62% of female undergraduate and 44% of female graduate students experienced sexual harassment. For graduate students, the perpetrator was most likely to be a faculty member or adviser, while for undergraduates the perpetrator was most likely to be a fellow student.

Another recent survey by the National Postdoctoral Association demonstrates the problem is also extensive in that population. It showed that around 700 women and men were harassed out of more than 2,700 who responded. It also confirmed that the majority of postdocs who were harassed did not report it, either because they didn’t think it was serious enough to report or because they thought it would make the workplace even more uncomfortable.

A 2014 survey of field scientists, led by University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, (UIUC) anthropologist Kathryn B. H. Clancy, was one of the first to show pervasive sexual misconduct against scientists doing fieldwork. More than 60% of women reported being harassed, and over 20% reported being assaulted. Clancy was surprised by the widespread denial among academic scientists, who seem to think that decades of data from the broader workforce—or even the field science survey results—don’t apply to them.

“Every professional society and department is contacting me saying, ‘We want to do your study in our department.’ Or you can just trust my data, and say ‘It’s probably like this here,’ ” says Clancy, who is a member of the National Academy of Sciences panel investigating sexual harassment. “Just because they haven’t had a Geoff Marcy doesn’t mean they don’t have some soul-searching to do.”

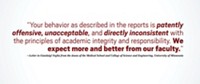

Natia Frank, a chemistry professor at the University of Victoria, was sitting at a table full of female chemists at a recent Gordon Research Conference when her colleagues began sharing their harassment experiences. “The stories I heard were horrifying and heartbreaking. Every single one of us had stories about retribution from senior members of the faculty,” says Frank, who is chairing a panel on harassment in her department after issues surfaced there.

Frank has heard chemistry called “the Marines of the sciences,” and she thinks that a historically male-dominated environment has helped chemists overlook harassing behavior by their faculty colleagues. Few women report it because the attitude within chemistry is “ ‘Oh, don’t cause problems, that’s just the way it is,’ ” Frank says. Graduate students or postdocs who are sexually harassed must then decide whether they want to fight their way through it or pursue another career path.

An unwanted experience

6%

of sexual harassment survivors report it.

25%

of women in the workplace experience sexual harassment.

10%

of men in the workplace experience sexual harassment.

48%

of university students report they have been sexually harassed.

34%

of female graduate and professional students report they have been harassed by a teacher, adviser, coworker, boss, or supervisor, compared with 11% of undergraduates.

Sources: Psychology of Women Quarterly 2016, DOI: 10.1177/0361684316644838; 2011 ABC News/Washington Post poll; 2015 Association of American Universities Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault & Sexual Misconduct

The emotional trauma of being sexually harassed, especially over an extended period, can take a toll on a person’s physical health and even derail a chemist’s career, potentially causing or exacerbating depression and other mental health issues that are particularly prevalent among grad students (C&EN, Aug. 7, page 28).

Sanda Sun, who is a chemistry instructor now at Irvine Valley College, says the sexual harassment she endured as a graduate student in the late 1970s by her research adviser elicited such significant mental and physical distress that she ended up in her school’s infirmary for two weeks. She also saw a psychiatrist to cope with her stress and anxiety.

Like it often does, the harassment Sun experienced began subtly. “I was under his wing on a research project, and he was explaining things,” she says of her adviser. “He would keep touching my hand with his hand, and that’s how it started. His home was far away, and he was even willing to miss the train to explain things for me. At first, I thought, ‘Wow, he’s so devoted.’ ”

But the attention from the married professor soon became uncomfortable and unwanted. “He always said, ‘Good morning.’ Then it led to a good morning hug, and then a good morning kiss.” One time, while Sun was in his office, he waited for his postdoc and another graduate student to leave so that he could be alone with her. “He started to kiss me, and I said, ‘Are you crazy?’ And I took off,” Sun says.

Sun says she reached out to other faculty members for help, but nobody was willing to get involved. She decided that she needed to leave her Ph.D. program. After she told her adviser of her plans, he showed up at her home bearing a gift and asking for her forgiveness. Before Sun realized what was happening, the professor removed his pants and exposed himself to her. “He said, ‘I’m in love with you. I want to make love to you.’ I puked. It was really so disgusting. I said, ‘Get out. Get out. You need to leave,’ ” Sun recounts.

Sun moved across the country to get as far away from the professor as possible. For years, she blamed herself for the harassment, wondering what she did to make him think she wanted an intimate relationship with him. “I wore tennis shorts to play tennis, very innocently. Nothing very sexy, just tennis shorts. I was wearing tennis shorts in and out of the lab, so I blamed myself.”

Chemist Mary K. Boyd, who recently became provost of Berry College, says that when there’s a power differential, it can be almost impossible for a student to say no. “The professor is writing a letter for them or serving as their research adviser or deciding who will receive travel funding to conferences. It’s really hard,” she says.

Boyd, who herself has experienced varying degrees of sexual harassment during her career, says female graduate students have told her that they are going into industry instead of academia because they believe sexual harassment will be taken more seriously in industry.

“I’m saddened to think that women may choose not to pursue a brilliant career in academia because of their experiences with sexual harassment,” Boyd says. “What is the potential loss in what they may have brought to the discipline if only they had felt they would be taken seriously?”

He would keep touching my hand with his hand, and that’s how it started.”

—Sanda Sun chemistry instructor, Irvine Valley College

He would keep touching my hand with his hand, and that’s how it started.”

—Sanda Sun chemistry instructor, Irvine Valley College

Feeling invalidated is among the reasons why a large majority of sexual harassment survivors never report the perpetrator. In one study that looked at sexual harassment of graduate students, of those who were harassed by professors, “we had 6% who reported it to any university source at all. Which means 94% did not,” says Jennifer J. Freyd, a University of Oregon psychology professor who is one of the coauthors of the research.

Advertisement

Another reason harassment survivors don’t report is embarrassment. “The shame of being involved in a harassment situation is quite overwhelming,” says “Nancy,” who was sexually harassed by a department administrator when she was a graduate student. “You don’t want anyone to know because you think they will wonder how a smart woman could ever get into a situation like that.”

Then there’s the fact that reporting may not make anything better—and may in fact make things worse. “There doesn’t appear to be a huge reason for me to step up and put myself out there when I don’t feel like there’s anything that’s going to happen as a result,” says “Lisa,” who was sexually harassed by a more senior colleague when she was a new assistant professor.

Lisa says she felt alone and vulnerable as her harassment intensified. “The professor became increasingly powerful within the department as years went by, and he actively made an effort to make my life hell,” she says. “Although many of my colleagues acknowledged his bad behavior, nobody seemed inclined to stand up to a tenured faculty member. One senior faculty member finally tried to stand up on my behalf, telling both the chair and the dean what was happening, but nothing appeared to be done. Or, at least, nothing changed.”

She considered leaving academia. “For about three years, that was a very serious thought in my head every day,” Lisa says. “The thing that kept me there was my students. I would walk into the lab, and I would see my students, and I would say, ‘Okay, this is the good part of my life.’ I realized I would be hurting their careers if I suddenly walked away, so that kept me going, especially through the toughest periods.”

For international students or postdocs, reporting sexual harassment could mean losing even the choice to continue because they could wind up deported. More than 70% of postdocs in the U.S. are in the country on work visas, notes Kate Sleeth, chair of the National Postdoctoral Association’s board of directors and associate dean of administration and student development at City of Hope medical center. “If someone wants to behave inappropriately, then they will say ‘You can’t tell anyone because I’ll send you home or you’ll lose your job,’ ” explains Sleeth, who was harassed as an international graduate student.

Bystanders can also be affected by sexual harassment. “Elizabeth,” who now works in industry, says that when she was a graduate student, she witnessed one of her classmates being sexually harassed by a professor during a recruitment weekend outing: “I was sitting in a booth with three other students and one professor. I felt something moving along my right thigh. I looked down and saw that the professor was running his hand along my fellow student’s left thigh. I made eye contact with the student, and she said, ‘Help me’ into my ear. The professor was drunk. He started pulling her toward him and whispering in her ear. I pulled her out of the booth with me on the premise of dancing. She told me that the professor was promising to help her get her Ph.D. if she put him on her committee.”

Elizabeth says that she and her other friends pressured the student to say something. Elizabeth considered reporting the incident herself but was torn. “You’re not sure if it’s going to be taken seriously if the person you’re reporting it for won’t back it up,” she says. “I didn’t want to say something if she was not going to speak up.”

Someone else reported the incident, Elizabeth recalls, and the chemistry department chair called each student into his office to talk about what happened. “The chair downplayed everything,” Elizabeth says. “He talked about the amount of money that was brought to the university by this person. I never filed a complaint or a report with anyone. It was all handled within the department, and it disgusts me to this day.

“When I saw what happened to [my colleague] and how I felt like we all just got railroaded into silence, I thought, ‘I don’t want to be here. I don’t want to be in this environment. It’s disgusting,’ ” Elizabeth says. She dropped out of the Ph.D. program and pursued a career in industry instead. “Some people think industry is where the harassment happens,” Elizabeth says. “But in industry, creeps get fired. In academia, they get funding.”

Struggle to confront

Callisto connects sexual assault survivors

Designed to empower survivors of sexual assault, Callisto is an online sexual assault reporting system that allows students to document and report their sexual assault. If they choose to, survivors can electronically send the record they have created to their school.

“With Callisto, we’re really trying to meet survivors where they’re at,” says Jessica Ladd, founder of Project Callisto, who was sexually assaulted as an undergrad. “We are here to help you understand and create a framework for what happened to you. Keep your options open, make the reporting choice that’s right for you, and increase the probability that if you do decide to come forward you’ll get the outcomes that you care about.”

The tool also has a matching function that enables survivors to report the perpetrator to the school only if another student has reported the same perpetrator. “People are just much more likely to be believed if there are two people saying that he did it,” says Jennifer Freyd, a psychology professor at the University of Oregon. “And once you know there are at least two victims, you realize there’s probably going to be three, four, five, et cetera. And most survivors, while they might not want to report for themselves, will often want to be socially proactive and stop it from happening to anyone else.”

“Throughout this process, we’re really trying to put control back in the hands of the survivor and let them make a choice about what they want,” Ladd says. The service is free for students, and partner schools pay a setup fee of $5,000 to $10,000, along with an annual fee of $14,000 to $40,000.

Many universities are getting tougher on harassers. But in most cases, the changes are not by choice.

Departments are unlikely to root out problem faculty on their own, just like families may protect an abuser in their midst for decades, says Heidi Lockwood, a Southern Connecticut State University philosophy professor who is an advocate for sexual harassment survivors at universities.

“Universities absolutely must step in,” Lockwood says. But “unless universities have a financial incentive to step in—meaning unless there are really stiff, tangible consequences for failing to step in—it’s not going to happen.”

A 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter from former president Barack Obama’s Education Department has been that lever for most universities. The letter pointed out that under Title IX, universities are responsible for having a system of tracking and responding to sexual harassment. The letter also emphasized universities’ legal liability if they neglect that obligation. (In a Sept. 7 speech, President Donald J. Trump’s secretary of education, Betsy DeVos, said that the department will review its approach to Title IX compliance and campus sexual misconduct.)

“Although they are historically a bastion of great creative ideas and high intellectual thought, universities are very reactionary when it comes to changing their own ways. Administrators are not bold, and it takes a crisis,” or fear of a crisis, to initiate change, says James Sears Bryant, a lawyer who has worked on several high-profile Title IX investigations at universities. “It’s good that they’re reacting now. The key is to continue the momentum and to continue to refine it and create a safe environment.”

At many schools, the Dear Colleague letter prompted reexamination of how they dealt with sexual assault and harassment, says Dana Scaduto, general counsel at Dickinson College and a member of the National Association of College & University Attorneys. Colleges and universities started paying attention to the issues, “and a lot of good has come out of it,” she says.

The Dear Colleague letter laid out some guidelines for how universities should deal with harassment but didn’t dictate a plan. Theoretically, that approach gave universities freedom to set up a sexual harassment reporting system that works for them. “The objective has to be to effectively address the issue,” Scaduto says. But every school is different, and “there’s not one answer that’s going to work on every campus.”

In practice, however, many schools don’t seem to be taking advantage of that flexibility. “Everyone wants to kind of be a copycat,” attorney Bryant says. “They want to adopt the practices of someone that’s just a little bit more famous or higher in the U.S. News & World Report [rankings].” That means many schools end up with similar policies surrounding harassment, such as rules regarding relationships between faculty and students and mandatory reporting of harassment by faculty.

Most schools “discourage” but don’t prohibit relationships between faculty and students, or schools allow such relationships if the professor does not directly supervise the student. However, a small but increasing number of universities—especially those that have had major harassment cases, like Yale, Stanford, and Northwestern—prohibit any relationship between a faculty member and a student, no matter the age or level of supervision.

“Some people think industry is where the harassment happens. But in industry, creeps get fired. In academia, they get funding.”

—“Elizabeth,” colleague of a sexual harassment survivor

“Some people think industry is where the harassment happens. But in industry, creeps get fired. In academia, they get funding.”

—“Elizabeth,” colleague of a sexual harassment survivor

Many faculty members are against these rules, citing cases of “true love” found between, for example, a graduate student and adviser. “But none of us knows anything about all of the flameouts that have ruined people’s careers,” UIUC’s Clancy says.

She is even more hesitant to allow these relationships because often the faculty member is a man and the graduate student is a woman, she says. “The woman does get her Ph.D. but then becomes a stay-at-home mom, and it just enables the career of the man,” Clancy says.

Davidson College’s Lewis sympathizes with faculty who believe they might not meet a partner off campus, but she also gives this advice: “Look elsewhere. Have you heard of Match.com?”

Even more contentious is the issue of mandatory reporting of sexual harassment. Many schools interpreted the Dear Colleague letter as a directive that every faculty member become a mandatory reporter of harassment.

Mandatory reporting is part of creating a well-understood process for how universities handle sexual harassment, says Kathleen Salvaty, formerly a Title IX officer at the University of California, Los Angeles, and now the first person in a new position overseeing sexual misconduct policies at all 10 UC campuses. “Ultimately, having a transparent and clear process for how we respond to reports is really important because it’s going to encourage people to report,” Salvaty says.

Advertisement

But advocates say mandatory reporting may actually hurt survivors by giving them no one to turn to after they are harassed. Lockwood, the Southern Connecticut professor and advocate, says faculty shouldn’t have to say to a hurting harassment victim, “ ‘Hey, anything you say can and will be used against you, can and will be reported to the administration,’ ” she says. “For very fragile victims, that can be something that pushes them over the edge into a downward spiral if they feel betrayed by a faculty member they trusted.”

Freyd, the University of Oregon psychologist, says that “any kind of sexual violence in the first place takes away control. When the response is to take away more control, even if it’s well intentioned, I think of it like a second concussion” that just adds to the damage.

She believes that Obama-era guidelines on mandatory reporting have been overinterpreted. “It doesn’t say everybody has to be a mandatory reporter. It says that some employees have to be designated that way,” she says. “Students tell us they’re much more willing to report if they believe that they’ll have control over what happens to the information.”

To that end, the University of Oregon is implementing student-directed reporting, which allows students to say what they want to have happen with the information they provide, Freyd says. Only high-level administrators are mandatory reporters, while regular professors and staff follow the student’s lead. The university is also one of roughly a dozen schools that have begun subscribing to Callisto, an online sexual harassment reporting system that launched two years ago (see box on page 33).

Whatever policies universities have, they often haven’t filtered down to faculty on the ground, such as chemistry department chairs. “I’ve been chair for four years. No information [on sexual harassment] has come to me in either a formal way or an informal way, so it’s just not been directly on my radar screen,” says Robert J. McMahon, immediate past chair of the chemistry department at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. The lack of information is changing, though. New department chairs at UW Madison now get training on sexual harassment policies and procedures.

Unfortunately, training department chairs or even faculty more broadly might not help address sexual harassment because current training approaches at most universities don’t seem to work. For example, in 2005 California began requiring two hours of sexual harassment training for state employees every two years, explains University of California, Irvine, classics professor Maria C. Pantelia, who was a member of a UC system-wide task force on sexual harassment. The task force found that even after biannual training, faculty, students, and postdocs still didn’t know how to report harassment. “The question is, ‘What are we doing wrong?’ ” Pantelia says. UC’s solution to the training problem right now is to add more training; for undergrads, it occurs three times in their first six to eight weeks, says Salvaty, the UC-wide Title IX officer.

UIUC’s Clancy believes one problem with training as it’s practiced now is that examples in video or online training never feel real or applicable to the viewer. She thinks the best training is when people get together and talk about the culture they want to create—ideally one that treats all faculty, staff, and students as professionals deserving of respect. “When you tie respect to workplace culture, then you’re not going to see as much sexual harassment,” she says.

Talking to colleagues, discussing sexual harassment data, and looking at real cases of harassment is the best way to get across the reality that harassment happens and causes harm, UCI’s Pantelia agrees. “What is lacking is a focus on awareness and a focus on the consequences that this kind of behavior has on others,” she says.

Changing culture

Judith N. Burstyn, chair of UW Madison’s chemistry department, is no stranger to issues of sexual harassment. When she was a graduate student, someone left sexually explicit messages in her books.

“Every woman experiences a certain level of sexual harassment, be it people groping them, be it people making sexually explicit remarks, be it whatever. Some of them are more intrusive and violent than others,” she says.

She has a porcupine sculpture in her office that she says represents her feelings about what it’s like to be a woman in science. “There are times when I would like to be a porcupine. I don’t like people who pat me, for example. I don’t think that’s ever appropriate, but I can tell you that happens all the time,” she says.

Burstyn believes that harassment will disappear only when chemistry department cultures change, which is something she intends to prioritize as chair. “Every work environment has power structures and power inequities, and these power inequities can be taken advantage of in ways that are gendered and ways that involve sexual harassment,” Burstyn says. Protecting students from harassment is especially important because they are “more vulnerable, less savvy, and less experienced, so they are particularly susceptible to being taken advantage of. That actually means that we as the power-holding people in academia should have a greater awareness and responsibility,” Burstyn says.

Others are also looking at what they can do to change their organization’s culture. After seeing high-profile cases of sexual harassment in the news, Nicholas J. Giordano, dean of the College of Sciences & Mathematics at Auburn University, began requiring sexual harassment training for new graduate students three years ago. At the 90-minute training session, which takes place in the fall when the school year begins, the university’s Title IX officer gives a presentation about sexual harassment, leads the group through role-playing activities, and discusses cases she has handled, Giordano says.

Curtis Shannon, chair of Auburn’s chemistry department, says the training “helps to clarify what the reporting channels should be, so if you’re a graduate student and you are the victim of sexual harassment, you understand the broad outlines of the Title IX requirements.”

“Every woman experiences a certain level of sexual harassment, be it people groping them, be it people making sexually explicit remarks, be it whatever.”

—Judith N. Burstyn, chemistry professor, University of Wisconsin, Madison

“Every woman experiences a certain level of sexual harassment, be it people groping them, be it people making sexually explicit remarks, be it whatever.”

—Judith N. Burstyn, chemistry professor, University of Wisconsin, Madison

A similar training session for faculty was particularly eye-opening, Shannon says. “The aha moment for me was when I realized that I am compelled to report this,” he says. “It changes your idea of what it means to be a faculty member. It reminds you that there’s a well-defined border between the faculty and the students. We’re not there to be friends with the students.”

Giordano doesn’t think training will stop harassers from harassing. But he hopes training will provide victims and bystanders with information on how to recognize and report sexual harassment.

Yale’s chemistry department was prompted to provide additional sexual harassment training after chair Gary Brudvig saw the results of the Association of American Universities report, which showed the majority of graduate student harassment comes from professors. Brudvig first invited the school’s Title IX officer to lead a discussion about harassment with the department’s faculty.

The faculty’s tendency before the session might have been “not only to smooth things over, but sort of keep it under wraps” if they heard about harassment, Brudvig says. Now, faculty know how to handle a problem confidentially but still take appropriate action, such as by reporting to Yale’s Title IX office, Brudvig says.

The faculty discussion in turn inspired the department’s director of graduate studies, Patrick L. Holland, to hold a mandatory sexual harassment education session for the department’s graduate students last year. The students looked at the survey data—which included disturbing results from Yale—and then broke into small groups to talk about different harassment scenarios.

“Once you have seen those graphs you’re aware, ‘Oh, this is actually happening, and it’s not a myth,’ ” says Yale graduate student Jaylissa Torres Robles.

A year after the session, Torres Robles remembers well the scenarios they discussed, including obvious examples like a professor asking for sexual favors to less obvious ones like a professor suggesting a student not have a baby while in graduate school. But she also remembers being surprised that some of her fellow students saw the same scenario in a different way than she did.

Although Torres Robles now knows what steps to take if she is harassed, she still isn’t sure how she would respond if it happens. “If you’re not in the situation, you’re like, ‘Yeah, I would [report] it, definitely.’ Because it’s my life and it’s my right,” she says. “But sometimes when people are in the situation they think about other things, like ‘Is this going to affect my career?’ ”

One important way to change the culture of departments would be to stop hiring new faculty who are harassers. Brudvig says the Yale human resources department conducts a background check, but otherwise there isn’t a way for the chemistry department to find out whether someone has been accused of harassment.

“People who have done things that I think are wrong will get hired again because they’ll bring in funding.”

—Richard N. Zare, chemistry professor, Stanford University

“People who have done things that I think are wrong will get hired again because they’ll bring in funding.”

—Richard N. Zare, chemistry professor, Stanford University

In harassment cases in which faculty are forced out of a school, often both sides sign a confidentiality agreement that prevents word from getting out publicly. But even when hiring institutions know about past complaints, it can be difficult to decide how much consideration to give to them. “There has to be some balancing of interests. If someone harassed another person and appropriate measures were taken to stop the harassment and restore the environment, does that make the person who was responsible unemployable for life?” asks Scaduto, the Dickinson lawyer.

At the same time, “Hiring committees can be very naive about the signs and a sort of profile of somebody who would repeat this kind of behavior,” says Davidson College’s Lewis. “If they hire someone who they suspect might repeat the behavior—or they don’t even bother to think about it—then they’re putting their students in danger.”

Advertisement

Money in particular can be a powerful incentive to downplay past bad actions. Stanford chemistry professor Richard N. Zare says he knows of cases when chemistry departments have turned a blind eye to behaviors that are otherwise unacceptable because the professor brings in a lot of money. “People who have done things that I think are wrong will get hired again because they’ll bring in funding. It happens when a university has the wrong priorities, when the priority is on funding,” he says.

That’s what U.S. Rep. Jackie Speier (D-Calif.) wants to stop with a bill she introduced last year that would require universities to report all substantiated findings of harassment to federal agencies that have awarded the harasser money within the past 10 years. The agency would then decide what to do with that information, but Speier hopes they would hold that person accountable. “My bill would be a first step to ending rampant sexual abuse and harassment in academia,” she says.

UIUC’s Clancy supports the bill because it has the potential to stop what some people call “Pass the Harasser,” she says. Also, “If people are going to be paying taxes for scientific research, should it really be going towards sexual harassers? I think it’s a pretty reasonable question to ask.”

Female chemistry professors are also tackling harassment on their own by doing things such as organizing support groups. Georgia Institute of Technology’s Elsa Reichmanis and another female faculty member started a monthly all-woman lunch group of several faculty and graduate students. “Basically, we’re trying to create a safe environment where students just feel comfortable talking,” says Reichmanis, who was harassed as a graduate student.

Reichmanis notes that the academic culture around harassment stands in stark contrast to her years at Bell Labs, where harassment training involved days-long workshops by trained facilitators rather than a one-hour video that no one takes seriously. “The corporate culture says, ‘This is our expectation for your behavior, and if you don’t conform to the expectation, you’re out the door,’ ” she says.

At the University of Victoria, Frank is leading a group to help address harassment in her department after reports surfaced from many women there, primarily undergraduates. “It was a cultural problem, and the cultural problem was that disrespectful things were being said,” Frank says. “Disrespectful behaviors were being tolerated by the faculty and staff.”

For example, “If a student reports that someone makes sexual advances toward her while she’s giving her poster at a meeting, the appropriate response is not, ‘Let it go, don’t make a big deal about it,’ ” Frank says. “The appropriate response is, ‘This is unprofessional, and I will speak to that individual.’ ”

Frank says about her male colleagues that “I think the desire is to do the right thing, but there is a sense of confusion and frustration—and a little bit of fear, now—around these issues.” Her aim is to make her fellow faculty members really understand what their goal should be: “to make the environment professional, where every individual is respected.”

Societies take action

While attending her first conference as an assistant professor, “Nicole” says that a senior faculty member from another institution came up to her and said he was a reviewer on one of her research proposals. “Later that night, we were alone, and then he grabbed me and kissed me and tried to—you know. It was pretty awful,” Nicole says.

“It never occurred to me that I wouldn't be safe at a conference with other chemists.”

—“Nicole,” sexual harassment survivor

“It never occurred to me that I wouldn't be safe at a conference with other chemists.”

—“Nicole,” sexual harassment survivor

“I’m thinking, ‘What do I do? Do I shove him? Do I do anything? He’s got my proposal.’ I learned right then and there to never be alone at a meeting. What a lesson to learn. It never occurred to me that I wouldn’t be safe at a conference with other chemists,” she says.

A growing number of scientific societies are recognizing that sexual harassment is a real problem at conferences, and organizations are taking tougher stands against it. “We haven’t looked very closely at what the consequences of sexual misconduct could be on our members, and that’s something I think that all societies should explore,” says Joanne Carney, director of the Office of Government Relations at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, noting that its code of conduct for its annual meeting addresses sexual harassment specifically.

The American Geophysical Union (AGU) has begun classifying sexual misconduct as scientific misconduct, and it is revising its code-of-conduct policy for meetings to reflect this change. “It’s a pretty big move, and I think it’s an important statement,” says AGU President Eric Davidson. “Historically, scientific misconduct has primarily been looked at through such things as plagiarism and falsification of data. As the scientific workforce has evolved, the issues have evolved, and so now it’s time to look at scientific misconduct through another lens.”

“This is about culture change, and what the ethics policy update does is it establishes our expectations for members of our society,” says AGU science director Billy Williams, who manages the organization’s ethics-related programs. He says the AGU Board of Directors is reviewing the revised policy this month. If approved, it will be made available to the public.

Changes in meeting policies are leading to more reports of sexual harassment. In 2014, after the Entomological Society of America (ESA) incorporated language about sexual misconduct into its code of conduct, it received its first report of sexual harassment at ESA’s annual conference. The number of reported cases grew to four in 2015. In 2016, a report came in about the same perpetrator as in 2014. “After our initial review of the complaints, we notified the member that if they did something similar at a future meeting, we would ask them to leave and not return to future meetings. In another meeting, we had to take that step after receiving a new complaint,” says Rosina Romano, ESA’s director of meetings. The organization has also stripped offenders of their ESA membership.

Romano says that ESA takes active steps to communicate its code of conduct to its members. All meeting registrants must agree to the code of conduct before they can complete their registration. In addition, the code of conduct is on the website, the program book, and a sign at registration, “and then our executive director reminds everybody during the opening plenary,” says Romano. The code of conduct is also communicated at meetings of the society’s branches.

“I don’t want women to feel like they can’t come to our meeting and share their research [because of an] unsafe atmosphere or feel like they need to go straight to their room at night because they don’t feel safe around other colleagues,” Romano says.

More societies should be following the lead of AGU and ESA, says Sherry Marts, a consultant who has worked for several societies. She says it is societies’ responsibility to tackle harassment at meetings.

“One of the things I like to remind associations of is that membership in a professional society—particularly membership in a scholarly society—is a privilege. It’s not a right,” Marts says. “When harassers do this at the meetings, it’s not just the targets they’re affecting. They’re infecting the entire atmosphere around them.”

The American Chemical Society, which publishes C&EN, developed its Volunteer/National Meeting Attendee Conduct Policy in 2013. The policy includes language about sexual harassment: “Harassment of any kind, including but not limited to unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment will not be tolerated.”

ACS General Counsel Flint Lewis says that since this revision, there have been “a handful” of reported incidents that required an investigation. “In one extreme case, we barred somebody from a national meeting for a year,” he says. “We take it very seriously. We want to ensure that our attendees and volunteers who are interacting with ACS have a very positive experience.”

Advertisement

He says the code of conduct is available to all members in the online program book, but he acknowledges that many people may not read it or be aware of it. He says that ACS has not yet placed any signs at the meeting about the code of conduct but that it should be considered. Lewis personally handles reports of harassment. If someone experiences harassment at an ACS meeting, they should report it to a staff member or to ACS’s operations office, he says.

In addition to updating its code of conduct for national meetings, in 2015, ACS streamlined its member expulsion provision in the ACS bylaws. That provision states that members whose conduct injures the society or adversely affects its reputation may have their membership revoked. Lewis says that to his knowledge no member has ever been expelled from the society, but that the sanction is intended to discourage misconduct. Also in the past couple of years, the society has added new procedures to rescind a national award or ACS Fellow designation for reasons including “misconduct.”

The ACS Women Chemists Committee (WCC) is considering adding sexual harassment to its areas of advocacy, which currently include awards and non-tenure-track faculty issues, says Laura S. Sremaniak, WCC chair and a chemistry professor at North Carolina State University. “WCC is concerned about the leaky pipeline,” Sremaniak says, referring to women dropping out of science careers. People debate how directly sexual harassment leads to the leaky pipeline, Sremaniak says, “but I think everybody suspects that sexual harassment is one major contributor towards the leaks. Neither women nor men should have to accept that sexual harassment is part of the price of admission into a promising career in the chemical sciences.”

Among the ideas that WCC is exploring is to have an anonymous reporting hotline at ACS national meetings. That idea was suggested by Stephanie Hare, a graduate student in chemistry at the University of California, Davis, and copresident of the nonprofit Alliance for Diversity in Science & Engineering.

Hare says the issue is very important to her because she has been sexually harassed at scientific conferences. Several times at poster sessions she has wound up talking to someone about her research for a long time. “I think it’s a really nice conversation, and then the poster session will end and basically I’ll be asked out on a date,” she says. “Or the next day, it will be clear that the person who was talking to me initially about my research at this poster session was expecting something more from me.

“When something like that has happened, and you have an awkward relationship with someone that you’re going to see at conferences in the future, it makes you less likely to even want to go to conferences,” she says.

Moving forward

“Neither women nor men should have to accept that sexual harassment is part of the price of admission into a promising career in the chemical sciences."

—Laura Sremaniak, a chemistry professor at North Carolina State University and chair of the ACS Women Chemists Committee

“Neither women nor men should have to accept that sexual harassment is part of the price of admission into a promising career in the chemical sciences."

—Laura Sremaniak, a chemistry professor at North Carolina State University and chair of the ACS Women Chemists Committee

The cost of sexual harassment to the sciences isn’t limited to loss of talent. Add to that the “businesses that are not established, the discoveries that are not made, the advancements that are not made for societal well-being,” says Rita R. Colwell, chair of the National Academy of Sciences’ Committee on Women in Science, Engineering & Medicine.

The committee is currently examining the scope of sexual misconduct in the sciences and how best to address it at all levels. “It’s timely because of the greater willingness to speak out, the greater willingness to resist and not tolerate sexual harassment,” she says. Additionally, “The studies that have been done over the years can be brought together and rational conclusions drawn and recommendations offered.”

The increased dialogue about sexual harassment is forcing changes. “The key is to take negative history and turn it into better futures,” says Bryant, the lawyer who has worked with universities on harassment. “We’ve had a real rash of bad stuff going on at major universities. I think the systems are better because of the bad things that have happened. I think there’s heightened awareness, and there are more progressive procedures. I think people are taking it seriously, and the sector will be better in the future than it has been in the past.”

And survivors of sexual harassment are feeling more empowered to speak out. Tara, who was propositioned by a professor, says that looking back, she wishes she had said something about the harassment she faced. “My actions could have helped someone else if I had reported this,” she says. “Who knows who came after me that I could have done something about?” .

For additional coverage, hear C&EN’s Linda Wang discuss sexual harassment in academia on WNPR’s “Where We Live” program.

Note: Jump to 22:35 to hear this segment.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter