Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Chemists synthesize longest polycatenane to date

String of 26 mechanically interlocked rings breaks record

by Bethany Halford

November 30, 2017

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 95, Issue 48

![Two types of ring, one in red and one in blue, link up to make this molecular model of a poly[12]catenane. Two types of ring, one in red and one in blue, link up to make this molecular model of a poly[12]catenane.](https://s7d1.scene7.com/is/image/CENODS/09548-notw4-4Dtransparent-700?$responsive$&wid=700&qlt=90,0&resMode=sharp2)

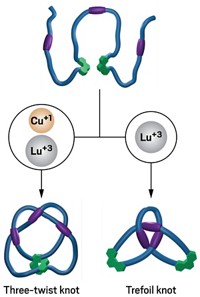

Through the use of some time-tested chemistry and clever monomer design, chemists led by the University of Chicago’s Stuart J. Rowan have managed to make a record-breaking polycatenane that mechanically links 26 ring-shaped molecules in a single chain. Their branched polycatenanes are even larger, boasting as many as 130 rings in a single mechanically interlocked molecule. The structures could have usual properties and would allow chemists to see if the flexible behavior seen in strands of metal chain-links also occurs on the molecular scale.

Chemists have been dreaming about making these types of polycatenanes ever since the University of Strasbourg’s Jean-Pierre Sauvage hooked two ring-shaped molecules together to make a basic catenane in 1983—a feat for which he shared the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Although chemists have managed to make polycatenanes with up to nine rings in a row, making longer chains has proven difficult.

“One of the key problems when you’re trying to make these types of materials is that you obviously have to form a ring at some stage,” Rowan explains. Such reactions are usually run at high dilution to guarantee that the two ends of the ring react with one another instead of with another molecule. But to make polymers, he says, the opposite is done: Reactions are run at high concentration to ensure the monomers react with one another. “It makes it tough to grow the polymer at the same time you’re doing the ring-closing step,” Rowan continues. “The key to our strategy was to decouple those.”

Rowan’s group took large C-shaped molecules equipped with two zinc-coordinating sites and alkenes on each end and combined them with large macrocycles also containing two zinc coordinating sites. When combined with the zinc ions, the C-shaped strands threaded through the macrocycles, forming large metallosupramolecular assemblies of various lengths containing C-shaped molecules alternating with macrocycles. The chemists then diluted these assemblies and did ring-closing metathesis to turn the C-shaped segments into rings. Finally, they removed the zinc ions (Science 2017, DOI: 10.1126/science.aap7675).

Rowan notes that his group synthesized the polycatenanes about five years ago and has spent the intervening time characterizing them. “We spent a lot of time trying to convince ourselves that these really are polycatenanes.”

“The simplicity of the approach—making use of the well-known templating followed by metathesis, but with cleverly designed building blocks—opens new avenues to fully characterize these wonderful polymers,” comments supramolecular systems specialist E. W. (Bert) Meijer of Eindhoven University of Technology. “This stunning achievement makes a dream come true.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter